Difference between revisions of "STORIES-OLD"

m |

|||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | <!-- OLD | ||

<div class="page-header" > <h1>Federation through Stories</h1> </div> | <div class="page-header" > <h1>Federation through Stories</h1> </div> | ||

| − | <!- | + | <p>[[File:Elephants.jpeg]]<br><small><center>Even if we don't mention him explicitly, this elephant is the main hero of our stories.</center></small></p> |

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>What the giants have been telling us</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>The invisible elephant</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The most interesting and impactful ideas are without doubt those that challenge our very order of things. But those same ideas also present the largest challenge to communication! A shared [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]] is what <em>enables us</em> to communicate. How can we make sense of new things, while they still challenge the order of things that gives things meaning?</p> | ||

| + | <p>When they attempt to share with us their insights, our visionaries appear to us like those proverbial blind or blind-folded men touching the elephant. They are of course far from being blind; they are <em>visionaries</em>! But the 'elephant' is invisible. We don't yet even have the words to describe him!</p> | ||

| + | <p>And so we hear our [[giants|<em>giants</em>]] talk about "the fan", "the hose" and "the rope" – while it's really the ear and the trunk and the tail of that big new thing they are pointing to.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>We begin with four dots</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The way we want to remedy this situation is, of course, by connecting the dots. Initially, all we can hope for is to show just enough of the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]] to discern its contours. Then interest and enthusiasm will do the rest. Imagine all the fun we'll have, all of us together, discovering and creating the details!</p> | ||

| + | <p>We'll begin here with four 'dots'. We'll introduce four [[giants|<em>giants</em>]], and put their ideas together. This might already be enough to give us a start.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The four stories we've chosen to tell will illuminate the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]]'s four sides (which correspond to the four [[keywords|<em>keywords</em>]] that define our initiative): | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>What constitutes good knowledge ([[design epistemology|<em>design epistemology</em>]])</li> | ||

| + | <li>What constitutes a good use of information technology ([[collective mind|<em>collective mind</em>]] paradigm, or [[knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]])</li> | ||

| + | <li>What constitutes a good use of our creative abilities ([[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]]) </li> | ||

| + | <li>In what way can we take good advantage of knowledge itself ([[guided evolution of society|<em>guided evolution of society</em>]]) </li> | ||

| + | </ul> </p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>These stories are vignettes</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>New thinking made easy</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The technique we'll use – the [[vignettes|<em>vignettes</em>]] – is in essence what the journalists use to make ideas accessible. They tell them through people stories! </p> | ||

| + | <p>We hope these stories will allow you to "step into the shoes" of [[giants|<em>giants</em>]], "see through their eyes", be moved by their visions.</p> | ||

| + | <p>By combining the [[vignettes|<em>vignettes</em>]] into [[threads|<em>threads</em>]], we begin to put the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]] together. The [[threads|<em>threads</em>]] add a dramatic effect; they make the insights of [[giants|<em>giants</em>]] enhance one another.</p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Right knowledge</h2></div> | |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>Modern physics gave us a gift</h3> |

| − | <p> | + | <p> |

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | (T)he nineteenth century developed an | ||

| + | extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not | ||

| + | only science but also the general outlook of great masses of | ||

| + | people. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p> | ||

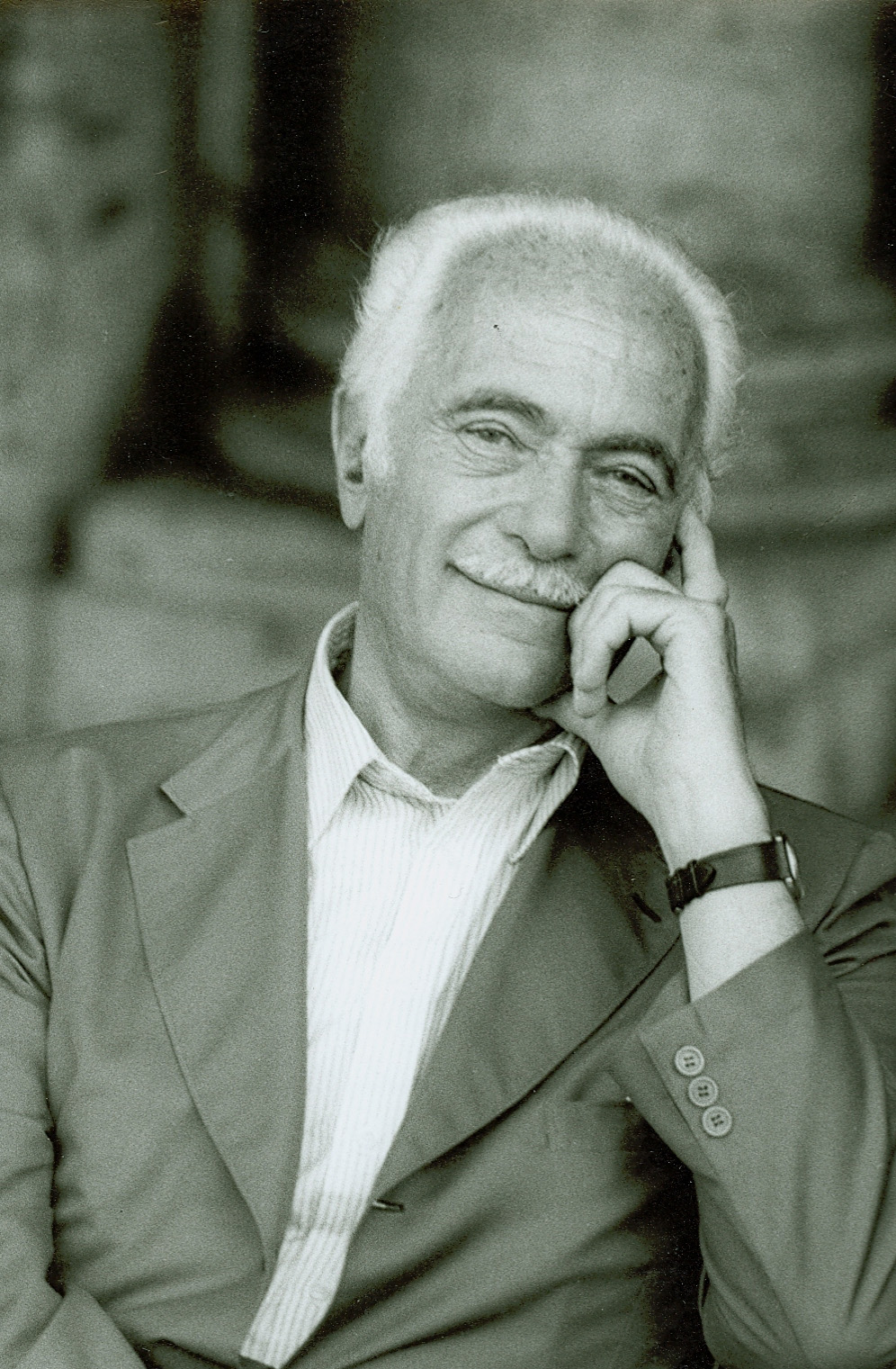

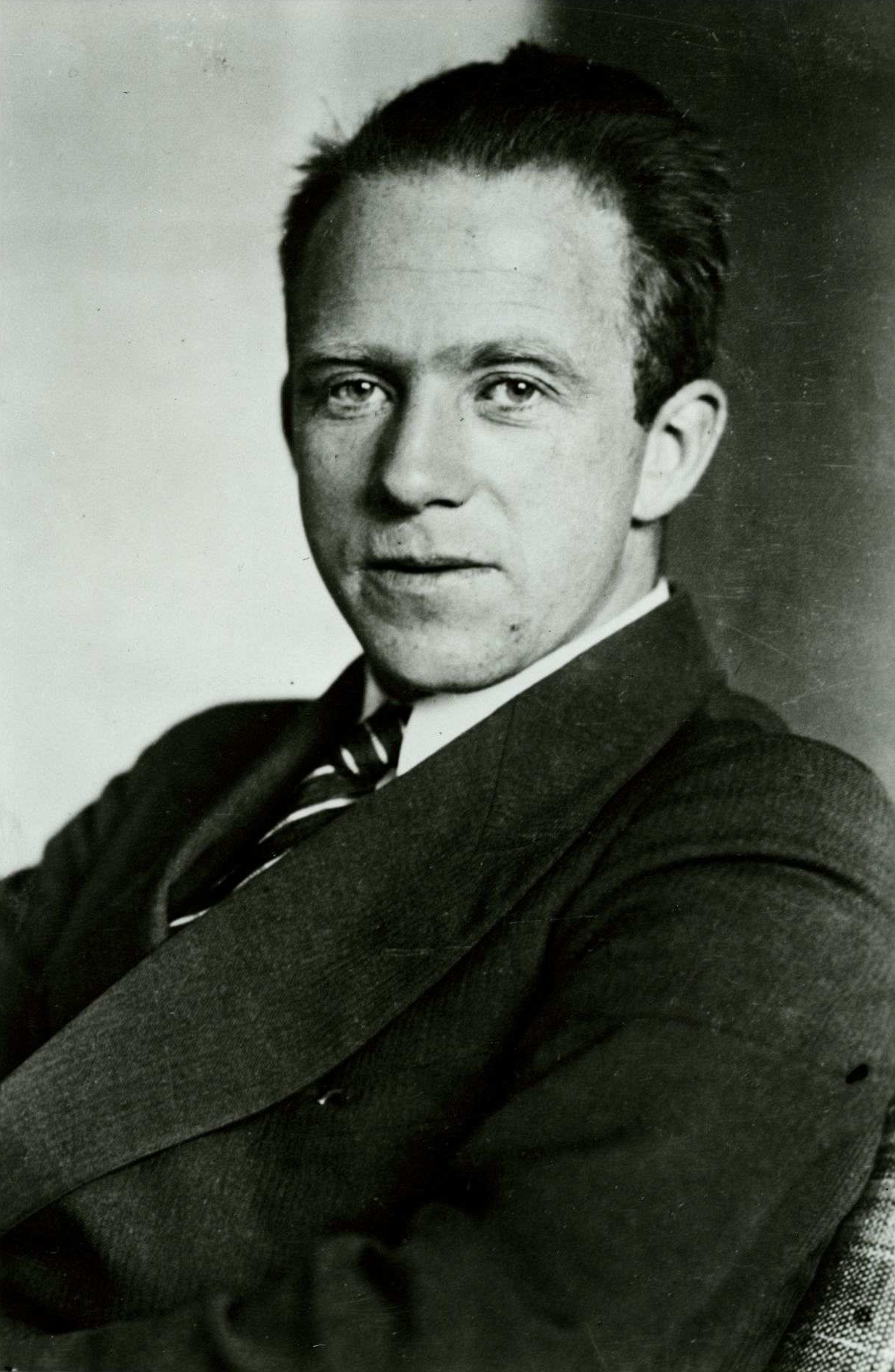

| + | <p>Werner Heisenberg got his Nobel Prize in 1932, "for the creation of quantum mechanics" he did while still in his twenties. </p> | ||

| + | <p>In 1958, this [[giants|<em>giant</em>]] of science looked back at the experience of his field, and wrote "Physics and Philosophy" (subtitled "the revolution in modern science"), from which the above lines have been quoted. </p> | ||

| + | <p>In the manuscript Heisenberg explained how science rose to prominence owing to successes in deciphering the secrets of nature. And how, as a side effect, its way of exploring the world became dominant also in our culture at large; in spite of the fact that frame of concepts was | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | so narrow and rigid that it was difficult to find a place in it for many concepts of our | ||

| + | language that had always belonged to its very substance, for | ||

| + | instance, the concepts of mind, of the human soul or of life. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Heisenberg.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Werner Heisenberg]]</center></small></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <p>Since | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had | ||

| + | provided, | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | whatever failed to fit in was considered unreal. This in particular applied to those parts of our culture in which our ethical sensibilities were rooted, such as religion, which | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | seemed now more or less only imaginary. (...) The confidence in the scientific method and in rational thinking replaced all other safeguards of the human mind. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p> | ||

| + | <p>Heisenberg then explained how the experience of modern physics constituted a rigorous <em>disproof</em> of this approach to knowledge; and concluded that | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | <em>The most important</em> change?!</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>What exactly happened</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The key to understanding this "dissolution of the narrow frame" is the so-called double-slit experiment. You'll easily find an explanations online, so we'll here only draw a quick sketch and come to conclusion. </p> | ||

| + | <p>A source of electrons is shooting electrons toward a screen - which, like an old-fashioned TV screen, remains illuminated at the places where an electron has landed. Between the source and the screen is a plate pierced by two parallel slits, so that the only way an electron can reach the screen is to pass through one of those slits.</p> | ||

| + | <p><em>One</em> of the slits?</p> | ||

| + | <p>What really happens is this: When the movement of the electron is observed, it behaves as a particle – it passes through one of the slits and lands on the corresponding spot on the screen.</p> | ||

| + | <p>When, however, this observation is <em>not</em> made, electrons behave as waves – they pass through <em>both</em> slits and create an interference pattern on the screen.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The question naturally arises – are electrons waves, or particles?</p> | ||

| + | <p>The answer is, of course, that they are neither. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>What this tells us about our "frames"</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Electrons thus defy both our words, and our reason.</p> | ||

| + | <p>This compelled the scientists to conclude that "wave" and "particle" are concepts, and corresponding behavioral patterns, which we have acquired through experience with common physical objects, such as water and pebbles. And that the electrons are simply something else – that they <em>behave unlike anything we have in experience</em>.</p> | ||

| + | <p>In the book Heisenberg talks about the physicists unable to describe the behavior of small quanta of matter in conventional language. The language of mathematics still works – but the common language doesn't!</p> | ||

| + | <h3>What this tell us about reality</h3> | ||

| + | <p>In "Uncommon Sense" Robert Oppenheimer – Heisenberg's famous colleague and the leader of the WW2 Manhattan project – tells about the double-slit experiment to conclude that <em>even our common sense</em>, however solidly objective it might appear to us, is really derived from our experience with common objects. And that it may no longer work – and <em>doesn't</em> work – when we apply it to things we <em>don't</em> have in experience.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Science rose from a tradition, whose roots are in antiquity, and whose goal was to understand and explain the reality as it truly is, through right reasoning.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Science brought us to the conclusion that <em>there is no right reasoning</em> that can lead us to that goal.</p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>What this tells us about science</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Heisenberg was, of course, not at all the only [[giants|<em>giant</em>]] who reached that conclusion. A whole <em>generation</em> of [[giants|<em>giants</em>]], in a variety of field, found evidence against the reality-based approach to knowledge.</p> | ||

| + | <p>We'll here let one of them, Benjamin Lee Whorf, summarize the conclusion.</p> | ||

| + | <p><blockquote>It needs but half an eye to see in these latter days that science, the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture, has reached, without having intended to, a frontier. Either it must bury its dead, close its ranks, and go forward into a landscape of increasing strangeness, replete with things shocking to a culture-trammelled understanding, or it must become, in Claude Houghton’s expressive phrase, the plagiarist of its own past." | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | It may be interesting to observe that this was written already in the 1940s – and published a decade later as part of a book.</p></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Whorf.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Benjamin Lee Whorf]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>We are at a turning point</h3> | ||

| + | <!-- ANCHOR --> | ||

| + | <span id="Story_of_Doug"></span> | ||

| + | <p>The Enlightenment empowered the human reason to rebel against the tradition and freely explore the world.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Several centuries of exploration brought us to another turning point – where our reason has become capable of self-reflecting; of seeing its own limitations, and blind spots.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The natural next step is to begin to expand those limitations, to correct those blind spots – by <em>creating</em> new ways to create knowledge.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | ------- | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Right use of technology</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>Digital technology calls for new thinking</h3> | ||

| + | <p><blockquote> | ||

| + | Digital technology could help make this a better world. But we've also got to change our way of thinking. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

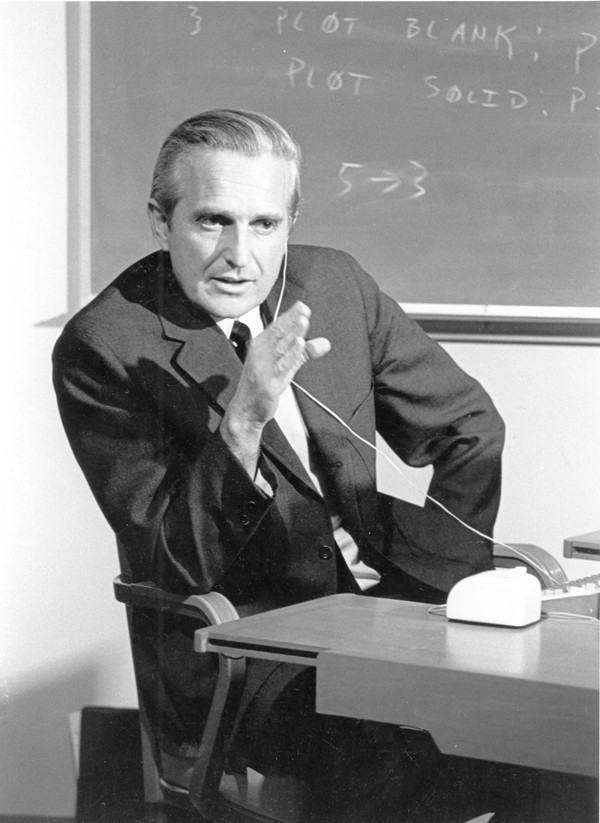

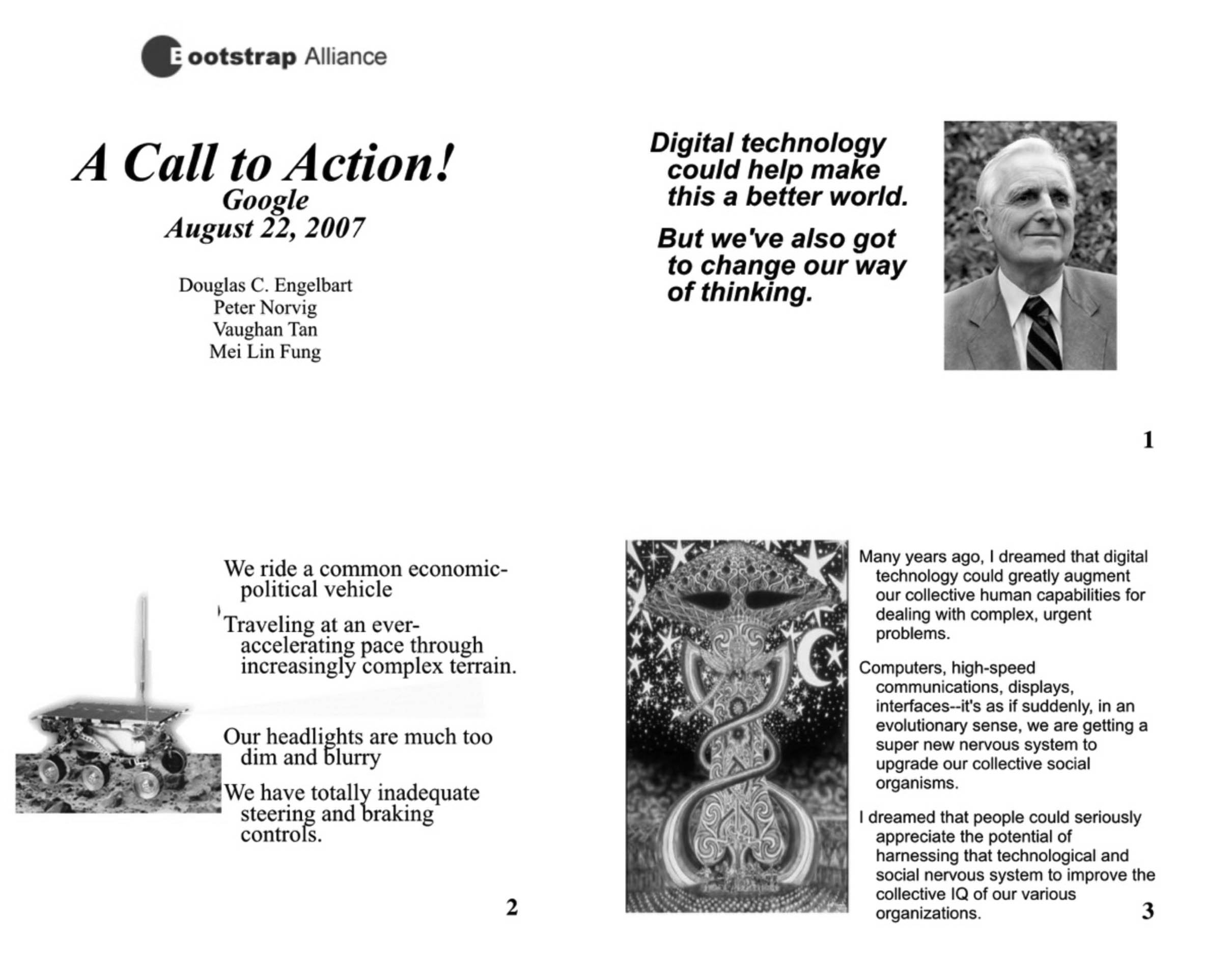

| + | These two sentences were intended to frame Douglas Engelbart's message to the world – which was to be delivered at a panel organized and filmed at Google in 2007. </p> | ||

| + | <h3>An epiphany</h3> | ||

| + | <p>In December of 1950 Engelbart was a young engineer just out of college, engaged to be married, and freshly employed. His life appeared to him as a straight path to retirement. He did not like what he saw.</p> | ||

| + | <p>So there and then he decided to direct his career in a way that will maximize its benefits to the mankind.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Facing now an interesting optimization problem, he spent three months thinking intensely how to solve it. Then he had an epiphany: The computer had just been invented. And the humanity had all those problems it didn't know how to solve. What if...</p> | ||

| + | <p>To be able to pursue his vision, Engelbart quit his job and enrolled in the doctoral program in computer science at U.C. Berkeley.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Engelbart.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Douglas Engelbart]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>Silicon Valley failed to hear its giant</h3> | ||

| + | <p>It took awhile for the people in Silicon Valley to realize that the core technologies that led to "the revolution in the Valley" were neither developed by Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, nor at the XEROX research center they took them from – but by Douglas Engelbart and his SRI-based research team. On December 9, 1998 a large conference was organized at Stanford University to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Engelbart's Demo, where the networked interactive digital media technology – which is today common – was first shown to the public. Engelbart received the highest honors an inventor could have, including the Presidental award and the Turing prize (a computer science equivalent to Nobel Prize). Allen Kay (a Silicon Valley personal computing pioneer, and a member of the original XEROX team) remarked "What will the Silicon Valley do when they run out of Doug's ideas?".</p> | ||

| + | <p>And yet it was clear to Doug – and he also made it clear to others – that the core of his vision was neither implemented nor understood. Doug felt celebrated for wrong reasons. He was notorious for telling people "You just don't get it!" The slogan "Douglas Engelbart's Unfinished Revolution" was coined as the title of the 1998 Stanford University celebration of the Demo, and it stuck.</p> | ||

| + | <p>On July 2, 2013 Doug passed away, celebrated and honored – yet feeling he had failed.</p> | ||

| − | + | <h3>The elephant was in the room</h3> | |

| + | <p>What is it that Engelbart saw, but was unable to communicate to all those famously smart people? </p> | ||

| + | <p>If we now tell you that the solution to this riddle is <em>precisely</em> the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]] we've been talking about, that whenever Doug was speaking or being celebrated, this elephant was present in the room but remained ignored – you probably won't believe us. A huge, spectacular animal in the midst of a university lecture hall – should that not be a front-page sensation and the talk of the town? (It may be better to imagine an elephant in a room at the inception of the <em>last</em> Enlightenment, when some people may have heard that such a huge animal existed, but nobody had yet seen one.)</p> | ||

| + | <p>To see that it was <em>systemic</em> thinking that inspired and guided Doug, consider the following excerpt (from an interview he gave as a part of a Stanford University research project), where he recalls the thought process that led to his "epiphany", and later to his project: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | I remember reading about the people that would go in and lick malaria in an area, and then the population would grow so fast and the people didn't take care of the ecology, and so pretty soon they were starving again, because they not only couldn't feed themselves, but the soil was eroding so fast that the productivity of the land was going to go down. Sol it's a case that the side effects didn't produce what you thought the direct benefits would. I began to realize it's a very complex world. I began to realize it's a very complex world. (...) Someplace along there, I just had this flash that, hey, what that really says is that the complexity of a lot of the problems and the means for solving thyem are just getting to be too much. So the urgency goes up. So then I put it together that the product of these two factors, complexity and urgency, are the measure for human organizations or institutions. The complexity/urgency factor had transcended what humans can cope with. It suddenly flashed tthat if you could do something to improve human capability to deal with that, then you'd realy contribute something basic. That just resonated. Then it unfolded rapidly. I think it was just within an hour that I had the image of sitting at a big CRT screen with all kinds of symbols, new and different symbols, not restricted to our old ones. The computer could be manipulating, and you could be operating all kinds of things to drive the computer. The engineering was easy to do; you could harness any kind of a lever or knob, or buttons, or switches, you wanted to, and the computer could sense them, and do something with it. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p> | ||

| + | <p>And if you are still in doubt – consider these first four slides from the <em>end</em> of Doug's career, which were intended to be part of his 2007 "A Call to Action" presentation at Google.</p> | ||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <p>[[File:Doug-4.jpg]]<br><small><center>The title and the first three slides that were prepared for Engelbart's "A Call to Action" panel at Google in 2007.</center></small></p> | ||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <p>You will notice that Doug's call to action had to do with changing our way of thinking. And that Doug introduced the new thinking with a variant of the bus with candle headlights metaphor we used to introduce our four main [[keywords|<em>keywords</em>]]. </p> | ||

| + | <p>And then there's the third slide, which introduces a whole new metaphor – a "nervous system". This was meant to explain Doug's specific intended gift to the emerging new paradigm in knowledge work – to which we'll turn next. </p> | ||

| + | <p>You might be wondering what happened with Engelbart's call to action? How did it fare? If you now google Engelbart's 2007 presentation at Google, you'll find a Youtube recording which will show that these four slides were not even shown at the event (the slides were shown beginning with slide four); that no call to action was mentioned; and that Engelbart is introduced in the subtitle to the video as "the inventor of the computer mouse".</p> | ||

| + | <h3>The 21st century enlightenment's printing press</h3> | ||

| + | <p>What was really Engelbart's intended gift to humanity? What was it that he saw, which the Silicon Valley "just didn't get"?</p> | ||

| + | <p>The printing press is a fitting metaphor in the context of our larger vision, because the printing press was the key technical invention that led to the Enlightenment, by making knowledge accessible.</p> | ||

| + | <p> If we now ask what technology might play a similar role in the <em>next</em> enlightenment, you will probably answer "the Web" or "the network-interconnected interactive digital media" if you are technical. And your answer will of course be correct.</p> | ||

| + | <p>But there's a catch! </p> | ||

| + | <p>While there can be no doubt that the printing press led to a revolution in knowledge work, <em>this revolution was only a revolution in quantity</em>. The printing press could only do what the scribes were doing – albeit incomparably faster! To communicate, people still needed to write and publish printed pages, and hope that the people who needed what they wrote would find them on a shelf.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The network-interconnected interactive digital media, however, is a disruptive technology of a completely <em>new</em> kind. It is not a broadcasting device, but in a truest sense <em>a nervous system</em> connecting people together! </p> | ||

| + | <p>There are two very different ways in which this sort of nervous system be put to use.</p> | ||

| + | <p>One of them is to use it as the printing press has been used – to increase the efficiency of what the people are already doing. To help them write and publish faster, and more. In the language of our metaphor, we characterize this way as using the new technology to re-implement the candle.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The other way is to reconfigure the document types, and the institutionalized patterns of knowledge development, integration and application, interaction and even the institutions to suit our society's needs, or in other words the function they need to fulfill in this larger whole – by taking advantage of the capabilities and of the very new nature of the new technology. The other way is to develop a <em>new</em> division, specialization and coordination of knowledge work – just as the cells in the human body body have developed through evolution, to take advantage of the nervous system that connects them together. </p> | ||

| + | <p>To see the difference between those two ways of using the technology, to see their practical consequences, imagine if your cells used your nervous system to merely <em>broadcast</em> data to your brain. Think about how this would impact your sanity!</p> | ||

| + | <p>You'll now have no difficulty seeing how our present way of using the technology has affected our <em>collective</em> intelligence!</p> | ||

| + | <p>In 1990 – just before the Web, and well before the mobile phone – Neil Postman would observe: | ||

| + | <blockquote>The tie between information and action has been severed. ...It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p> | ||

| + | <h3>Engelbart's legacy</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Engelbart wanted to show us, and to help materialize, the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]]; but since we couldn't see it – he ended up with only a little mouse in his hand (to his credit)!</p> | ||

| + | <p>So if we would now undertake to give him proper credit – <em>what is it that Engelbart must be credited for?</em></p> | ||

| + | <p>As we speak, please notice how systematically this unusual mind was putting together all the necessary vital pieces or building blocks – so that the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]] may come into being.</p> | ||

| + | <p>One of them we've already mentioned – the "nervous system", for which Doug's technical keyword was CoDIAK (for Concurrent Development, Integration and Application of Knowledge). It's the 'nervous system'. That – and not "the technology" – is what Engelbart and his team showed on their 1968 famous demo. The demo showed people interacting directly with computers, and through computers – via a network by which the computers were connected – with each other. Doug and his team experimented to make this interaction as direct as possible; with a "chorded keyset" under his left hand, a mouse with three buttons under his right hand, and a computer screen before his eyes, a knowledge worker became able to "develop. integrate and apply knowledge" in collaboration, and concurrently with others – without ever even moving his body!</p> | ||

| + | <p>To get an idea of the importance of this contribution, think about what a functioning "collective nervous system" could do to our collective capability to deal with complexity and urgency. Imagine yourself walking toward a wall, and that your eyes see that – but they are trying to communicate it to your brain by writing academic articles in some specialized field of knowledge.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The second key Engelbart's contribution – which is, as we have just seen, <em>necessary</em> if we should take advantage of the first one – was what we've been calling [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]]. <em>Engelbart created (to our knowledge) the very first methodology for [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] </em> – already in 1962, six years before the systems scientists met in Bellagio to develop their own approach to it (which will be part of our next story). Engelbart called his method "augmentation", and conceived as a way to "augment human capabilities", individual <em>and</em> collective, by combining elements of the "human system" and the "tool system". [[systemic innovation|<em>Systemic innovation</em>]] he called "human system – tool system co-evolution", or more simply "bootstrapping". </p> | ||

| + | <p>We leave the rest – to see how the "open hyperdocument system", the "networked improvement community", the "dynamic knowledge repository" and numerous other Engelbart's inventions were essential building blocks in a new order of things, or knowledge work [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]], or vital organs of our metaphorical [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]]. You'll find them explained in the mentioned videotaped 2007 presentation at Google. You may then also notice that they don't really make the kind of sense they're supposed to make – when presented outside of the context that the first three slides were supposed to provide (the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]]).</p> | ||

| + | <p>We conclude that while Engelbart was recognized, and celebrated, as a technology developer – his contribution was <em> to human knowledge</em> – and hence in the proper sense <em>academic</em>. </p> | ||

| − | < | + | <h3>Bootstrapping – the unfinished part</h3> |

| + | <p>In a similar vein, there can hardly be any doubt about what exactly it was that, Doug felt, he was leaving unfinished. It's what he called "bootstrapping" – which we've adopted as one of our [[keywords|<em>keyword</em>]]. </p> | ||

| + | <p>Bootstrapping was so central to Doug's thinking, that when he and his daughter Christina created an institute to realize his vision, they called it "Bootstrap Institute" – and later changed the name to "Bootstrap Alliance" because, as we shall see in a moment, an alliance rather than an institute is what's needed to bring bootstrapping to fruition. Engelbart would begin the "Bootstrap Seminar" (which he taught through he Stanford University to explain his vision and create an alliance around it) by sharing his portfolio of [[vignettes|<em>vignettes</em>]] – which were illustrating the wonderful and paradoxical challenge of people to see an emerging paradigm. Then he would have the participants discuss their own experiences with paradigm shifts in pairs. Then he would talk more about the paradigms.</p> | ||

| + | <p>When it became clear that Engelbart's long career was coming to an end, "Bootstrap Dialogs" were recorded in the Stanford University's film studio as a last record of his message to the world. Jeff Rulifson and Christina Engelbart – his two closest collaborators in the later part of his career – were conversing with Doug, or indeed mostly explaining his vision in his presence, with Doug nodding his head. And when they would turn to him and ask "So what do you say about this, Doug?" he would invariably say something like "Oh boy, I think somebody should really make this happen. I wonder who that might be?" We made an examle, {https://youtu.be/cRdRSWDefgw this three-minute excerpt], available on Youtube – where Doug also talks about the meaning of "bootstrapping".</p> | ||

| + | <p>The word itself should remind you of "lifting yourself up by pulling your bootstraps" – which is of course in physical sense impossible, yet the magic works <em>as a metaphor</em>. The idea is to use your intelligence to boost your intelligence. Or applied to [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] – to recreate one's own system, and thus become able to recreate other systems.</p> | ||

| + | <p>To Engelbart "bootstrapping" meant several related things.</p> | ||

| + | <p>First of all – and this is the succinct way to understand the core of his vision – Engelbart, as a systemic thinker, clearly saw that the most effective way one can invest his creative capabilities (and make "the largest contribution to humanity") is by applying them to creativity itself – and improving <em>everyone's</em> creative capabilities, and our ability to make good use of the results thereof.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Furthermore, Doug the systemic thinker knew that positive feedback leads to exponential growth. And so he saw [[bootstrapping|<em>bootstrapping</em>]] as the only way our capabilities to cope with the accelerated growth of the "complexity times urgency" of our problems.</p> | ||

| + | <p>And finally – Doug saw that talking about how to "solve our problems" or "improve our systems", or writing academic articles about that, is just not good enough. (He saw, in other words, what we've been calling the [[Wiener's paradox|<em>Wiener's paradox</em>]].) So [[bootstrapping|<em>bootstrapping</em>]] then emerges as what we must do if we <em>really</em> want to make a difference.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | ------- | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Right way to innovate</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>Democracy for the third millennium</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | The task is nothing less than to build a new society and new institutions for it. With technology having become the most powerful change agent in our society, decisive battles will be won or lost by the measure of how seriously we take the challenge of restructuring the “joint systems” of society and technology. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

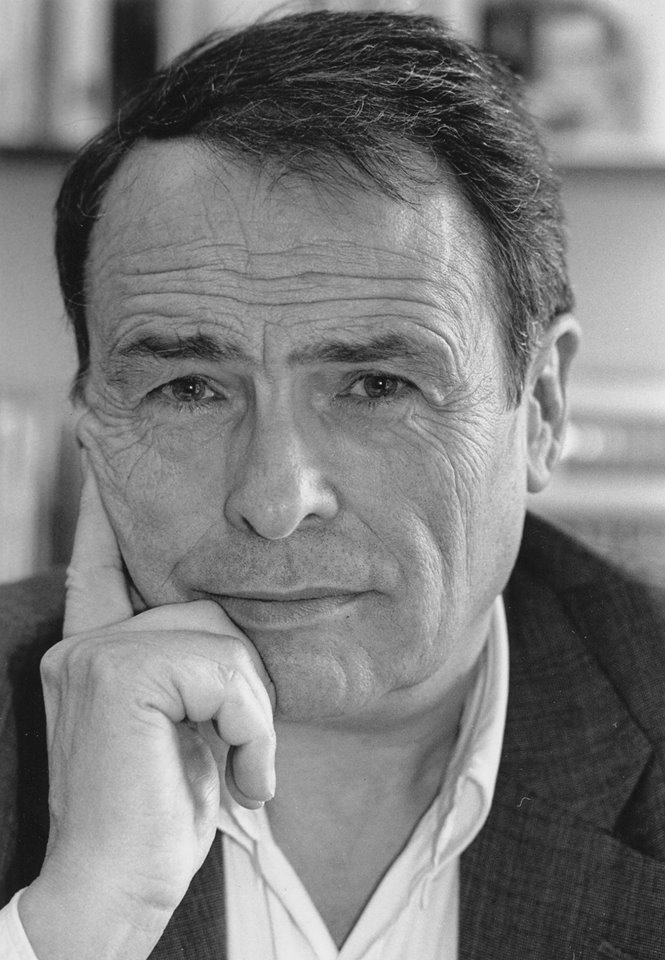

| + | Erich Jantsch reached and reported the above conclusion quite exactly a half-century ago – at the time when Doug Engelbart and his team were showing their demo.</p> | ||

| + | <p>We weave these two histories together – the story of Engelbart and the story of Jantsch – in the second book of Knowledge Federation trilogy. So far we've seen that we need the capability to rebuild institutions and institutionalized patterns of work and interaction to be able to take advantage of fundamental insights and of new information technology. (Or in the language of Thomas Kuhn, we have seen that this is necessary to resolve the reported anomalies in those two key domains of knowledge work). By telling about Erich Jantsch we'll be able to bring in the third. How shall we call it? Our choice is in the title of this section – which is also the subtitle of the book we've just mentioned. We could just as well be talking about "sustainability" or "thrivability" or "creative action". Why we chose "democracy" will hopefully become transparent after you've read a bit further.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>First things first</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Jantsch got his doctorate in astrophysics in 1951, when he was only 22. But having recognized that more physics is not what our society most urgently needs, he soon got engaged in a study (for the OECD in Paris) of what was then called "technological planning" – i.e. of the strategies that different countries (the OECD members) used to orient the development and deployment of technology. (<em>Are there</em> such strategies? – you might rightly ask. Isn't it "the market and only the market" the answers to such questions? You'll have no difficulty noticing the underlying <em>big question</em> – What is guiding us toward our future? And that how we answer this question splits us into into two (subcultures, or paradigms): Those of us who believe in "the invisible hand" – and those who don't. Recall Galilei...)</p> | ||

| + | <p>And so when The Club of Rome was to be initiated (fifty years ago at the time of this writing) as an international think tank whose mission was to evolve and to <em>be</em> the evolutionary guidance or the 'headlights' to our global society (as we shall see in our next story), it was natural that Jantsch would be chosen to put the ball in play, by giving a keynote talk.</p></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Jantsch.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Erich Jantsch]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3">< | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> |

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>How systemic innovation got conceived</h3> | ||

| + | <p>With a doctorate in physics, it was not difficult to Jantsch to put two and two together and see what needed to be done. If our civilization is on a disastrous course, if it lacks (as Engelbart put it) suitable headlights and braking and steering controls, or (to use a cybernetician's more scientific tone) suitable "information and control", then there's a single capability that we as society need to be able to correct this problem – the capability to <em>rebuild</em> our systems. So that we may <em>become</em> capable of seeing where we are going, and steering.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Another way of saying this is that [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] <em>is</em> steering – because without it we can neither choose our evolutionary course nor our future. And even the <em>right</em> information remains impotent, and ultimately useless.</p> | ||

| + | <p>So right after The Club of Rome's first meeting, Jantsch gathered a group of creative leaders and researchers, mostly from the systems community, in Bellagio, Italy, to put together the necessary insights and methods. The result was a [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] methodology. By calling it "rational creative action", Jantsch suggested a message that is of our central interest: Certainly there are many ways in which we can be creative. But if our creative action is to be <em>rational</em> – then here is what we need to do. </p> | ||

| + | <p>Rational creative action begins with forecasting, which explores different future scenario, and ends with an action selected to enhance the likelihood of the <em>desired</em> scenario or scenarios. What they called "planning" had nothing to do with the kind of planning that was at the time used in the Soviet Union: | ||

| + | <blockquote>[T]he pursuance of orthodox planning is quite insufficient, in that it seldom does more than touch a system through changes of the variables. Planning must be concerned with the structural design of the system itself and involved in the formation of policy.” | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | Do we really need [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]]? Can't we just rely on "the survival of the fittest" and "the invisible hand"? Jantsch observes that the nature of the problems we create when relying on the "invisible hand" is compelling us to develop [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] as our <em>next</em> evolutionary step. | ||

| + | <blockquote>We are living in a world of change, voluntary change as well as the change brought about by mounting pressures outside our control. Gradually, we are learning to distinguish between them. We engineer change voluntarily by pursuing growth targets along lines of policy and action which tend to ridgidify and thereby preserve the structures inherent in our social systems and their institutions. We do not, in general, really try to change the systems themselves. However, the very nature of our conservative, linear action for change puts increasing pressure for structural change on the systems, and in particular, on institutional patterns.</blockquote></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Back to democracy</h3> | ||

| + | <p>You might now already be having an inkling of the contours of the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]]; how all these seemingly disparate pieces – the way we use the language, the way we use information technology, and the way we go about resolving the large contemporary issues – can snuggly fit together <em>in two entirely different ways</em>!</p> | ||

| + | <p>Take, for example, the word "democracy". In the old [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]], democracy is what it is – the "free press", "free elections", the representative bodies. As long as they are all there, by definition – we live in a democracy. The nightmare scenario in this order of things is a dictatorship, where the dictator has taken away from the people all those conventional instruments of democracy, and he's ruling all by himself.</p> | ||

| + | <p>But there is another, <em>emerging</em> way to look at the world, and at democracy in particular – to consider it as a social order where the people are in control; where they can control their society, and steer it and choose their future. The nightmare scenario in this order of things is what Engelbart showed on his second slide mentioned above – it's an order of things where <em>nobody</em> has control! Simply because the whole thing is structured so that <em>nobody</em> can see where the whole thing is headed, or change its course.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Back to bootstrapping</p> | ||

| + | <p>In this second order of things (where we don't rely our civilization's and our children's future on "the invisible hand" but use the best available knowledge to see where we are headed and steer</p> – [[bootstrapping|<em>bootstrapping</em>]] is readily seen as the very next and vitally important step. We must adapt our institutions to give us the capabilities we lack. But those institutions – that's us, isn't it? Nobody has the power, or the knowledge, to order for example the university to recreate itself in a certain way. The university itself will need to do that!</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>The emerging role of the university</h3> | ||

| + | <p>If [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] is the necessary new capability that our systems and our civilization at large now require, to be able to steer a viable course into the future – then who (that is, what institution) may be the most natural and best qualified to foster this capability? Jantsch concluded that the university (institution) will have to be the answer. And that to be able to fulfill this role, the university itself will need to update its own system. | ||

| + | <blockquote>[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewal. It may have to become a political institution, interacting with government and industry in the planning and designing of society’s systems, and controlling the outcomes of the introduction of technology into those systems. This new leadership role of the university should provide an integrated approach to world systems, particularly the ‘joint systems’ of society and technology.” </blockquote> | ||

| + | In 1969 Jantsch spent a semester at the MIT, writing a 150-page report about the future of the university, from which the above excerpt was taken, and lobbying with the faculty and the administration to begin to develop this new way of thinking and working in academic practice.</p> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-6"><h3> | + | <h3>The evolutionary vision</h3> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>This however brief sketch of Erich Jantsch vision and legacy would be unjustly incomplete without at least mentioning his studies of evolution.</p> |

| + | <p>Jantsch had at least two strong reasons for this interest. The first one was his insight – or indeed lived experience – that the basic institutions and other societal systems tend to be too immense to be significantly affected by any human act. Working with evolution, however, gives us an entirely new degree of freedom, and of impact. "I'm a trimtab", Fuller wrote. (If this may evoke associations with Engelbart's "bootstrapping", then you are spot on!)</p> | ||

| + | <p>Another reason Jantsch had for this interest was that he saw it as a genuinely new paradigm in science, and an emerging scientific frontier. | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | With Ervin Laszlo we may say that having addressed ourselves to the understanding and mastering of change, and subsequently to the understanding of order of change, or process, what we now need is an understanding of order of process (or order of order of change) – in other words, an understanding of evolution. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | While the traditional cybernetic approach aims at stability and equilibrium, evolution, and life itself, are served by <em>dys</em>equilibrium. While the traditional science aims at objectivity, the evolutionary paradigm requires that we see ourselves as <em>part of</em> the system – and that we evolve in a way that may best suit the system's evolution. (If this is reminding you of the academic reality on the other side of the metaphorical [[mirror|<em>mirror</em>]], then again you are spot on!) While the traditional sciences tend to focus on reversible phenomena, evolution is intrinsically <em>irreversible</em>. </p> | ||

| + | <p>Towards the end of his life, Jantsch became increasingly interested in the so-called "spiritual" phenomena and practices – having perceived among them potential "trimtabs".</p> | ||

| + | <p>Jantsch spent the last decade of his life living in Berkeley, teaching sporadic seminars at U.C. Berkeley and writing prolifically. Ironically, the man who with such passion and insight lobbied that the university should take on and adapt to its vitally important new role in our society's evolution – never found a home and sustenance for his work at the university. </p> | ||

| + | <p>In 1980 Jantsch published two books about "the evolutionary paradigm", and passed away after a short illness, only 51 years old. An obituarist commented that his unstable income and inadequate nutrition might have contributed to this early end. In his will Jantsch asked that his ashes be tossed into the ocean, "the cradle of evolution".</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2 style="color:red">Reflection</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>The future of innovation</h3> | ||

| + | <p>We offer this [[reflection about the future of innovation]] to give you a chance to pause and connect the dots.</p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | ------- | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Right handling of our planetary condition</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>An unknown hero</h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | The human race is hurtling toward a disaster. It is absolutely necessary to find a way to change course.</blockquote> | ||

| + | [[Aurelio Peccei]] – the co-founder, firs president and the motor power behind The Club of Rome – wrote this in 1980, in One Hundred Pages for the Future, based on this global think tank's first decade of research.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Peccei was an unordinary man. In 1944, as a member of Italian Resistance, he was captured by the Gestapo and tortured for six months without revealing his contacts. Here is how he commented his imprisonment only 30 days upon being released: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | My 11 months of captivity were one of the most enriching periods of my life, and I regard myself truly fortunate that it all happened. Being strong as a bull, I resisted very rough treatment for many days. The most vivid lesson in dignity I ever learned was that given in such extreme strains by the humblest and simplest among us who had no friends outside the prison gates to help them, nothing to rely on but their own convictions and humanity. I began to be convinced that lying latent in man is a great force for good, which awaits liberation. I had a confirmation that one can remain a free man in jail; that people can be chained but that ideas cannot. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3">[[File:Peccei.jpg]]<br><small><center>[[Aurelio Peccei]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <p> Peccei was also an unordinarily able business leader. While serving as the director of Fiat's operations in Latin America (and securing that the cars were there not only sold but also produced) Peccei established Italconsult, a consulting and financing agency to help the developing countries catch up with the rest. When the Italian technology giant Olivetti was in trouble, Peccei was brought in as the president, and he managed to turn its fortunes around. And yet the question that most occupied Peccei was a much larger one – the condition of our civilization as a whole; and what we may need to do to take charge of this condition.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>How to change course</h3> | ||

| + | <p>In 1977, in "The Human Quality", Peccei formulated his answer as follows: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p> | ||

| + | <p>And to leave no doubt about this point, he framed it even more succinctly: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | On the morning of the last day of his life (March 14, 1984), while working on "The Club of Rome: Agenda for the End of the Century", Peccei dictated to his secretary from a hospital bed that | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | human development is the most important goal. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>Peccei's and Club of Rome's insights and proposals (to focus not on problems but on the condition or the "problematique" as a whole, and to handle it through systemic and evolutionary strategies and agendas) have not been ignored only by "climate deniers", but also by activists and believers. </p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2 style="color:red">Reflection</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>Connecting the dots</h3> | ||

| + | <p> </p> | ||

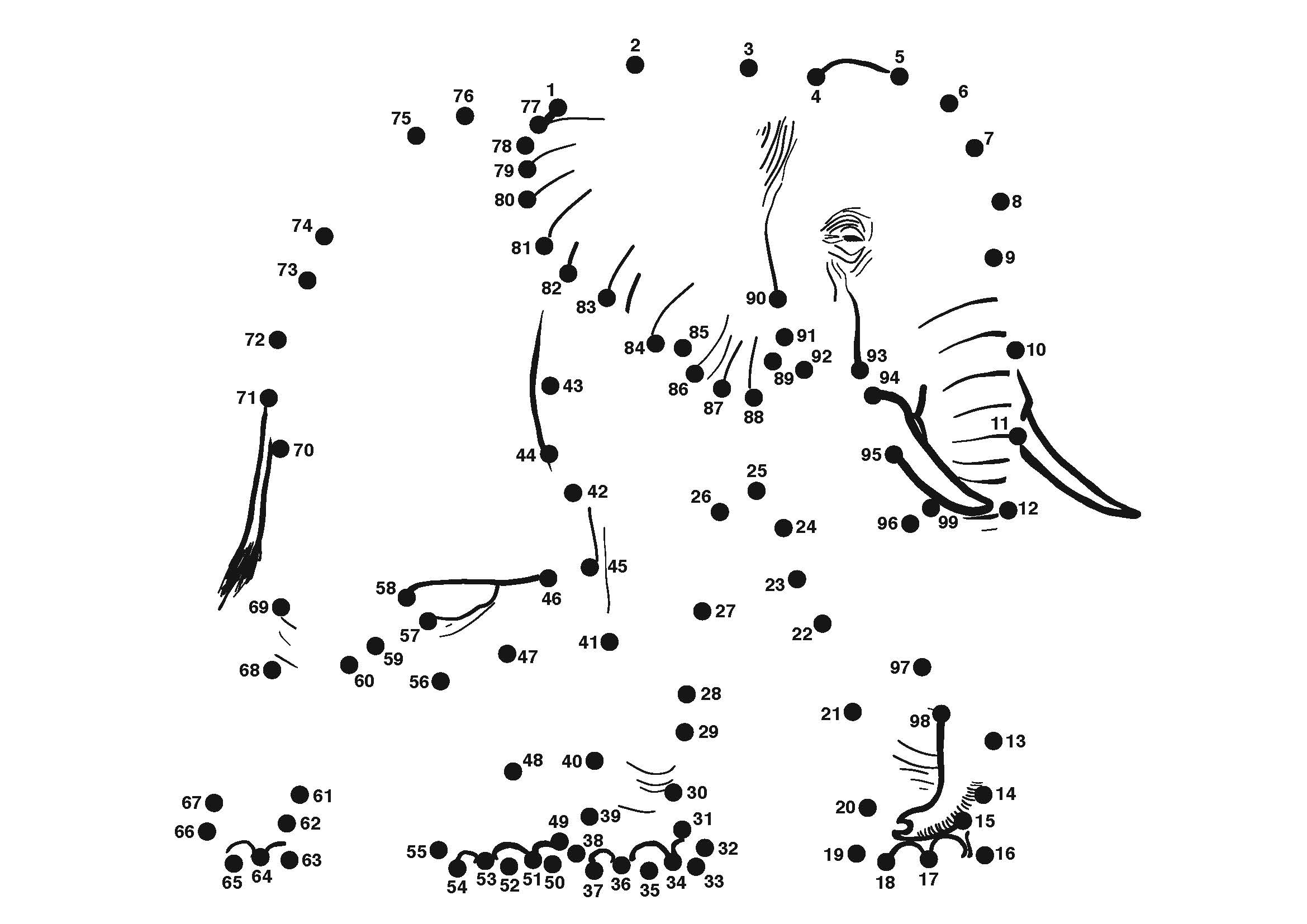

| + | <p>[[File:Elephant.jpg]]<br><small><center>It remains to connect the dots.</center></small></p> | ||

| + | <p> </p> | ||

| + | <p>In what way can "a great cultural revival" <em>realistically</em> happen?</p> | ||

| + | <p>The key strategic insight here is to see why a <em>very</em> large change can be easy, even when smaller and obviously necessary changes might seem impossible: You cannot put an elephant's ear on a mouse – even if this might vastly improve his hearing.</p> | ||

| + | <p>On the other hand, large, sweeping changes can happen by a landslide, as each change, like a falling domino, naturally leads to another. </p> | ||

| + | <p>So the key question is – <em>How to begin</em> such a change?</p> | ||

| + | <p>The natural first step, we propose, is to <em>connect the dots</em> – and see where we are going or <em>out to</em> be going, see how all the pieces snuggly fit together.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Already combining Peccei's core insight with the one of Heisenberg will bring us a large step forward</p> | ||

| + | <p>Peccei observed that our future depends on our ability to revive <em>culture</em>, and identified improving the human quality is the key strategic goal. Heisenberg explained how the "narrow and rigid" way of looking at the world that the 19th century science left us with was <em>damaging</em> to culture – and in particular to its parts which traditionally governed human ethical development, notably the religion.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Can we build on what Heisenberg wrote, and recreate religion in an entirely new way – which would support us in "great cultural revival"?</p> | ||

| + | <p>The Garden of Liberation [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] (see Federation through Applications) and the Liberation book (the first in Knowledge Federation Trilogy, see Federation through Conversations) will show that indeed we can! Religion is now often assumed to be no more than a rigid and irrational adherence to a belief system. A salient characteristic of the described religion-reconstruction [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] is to <em>liberate</em> us (that is, <em>both</em> religion <em>and</em> science) from holding on to <em>any</em> dogmatically held beliefs!</p> | ||

| + | <p>Combining the core insights of Jantsch and Engelbart is even easier, as they are really just two sides of a single coin.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Jantsch identified [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] as that key lacking capability in our capability toolkit, which we must have to be able to steer our ride into the future. Engelbart identified it as the capability which we need to be able to use the new technology to our advantage. We now have the technology that not only enables, but indeed <em>demands</em> [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]]. What are we waiting for?</p> | ||

| + | <p>When you browse through our collection of [[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] that are provided in Federation through Applications, and see concretely and in detail the larger-than-life improvements of our condition that can be achieved by improving or reconstructing our core institutions or systems, when you see that an avalanche-like or Industrial Revolution-like wave of change that is ready to occur – then you'll have but one question in mind: "Why aren't we doing this?!" </p> | ||

| + | <p>A [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] answer to this <em>most interesting</em> question is given in Federation through Conversations – by weaving together insights of [[giants|<em>giants</em>]] in the humanities. We shall see how what we've been calling "our reality picture" is likely to be seen as our [[doxa|<em>doxa</em>]] – a power-related instrument of socialization that keeps us in a certain systemic status quo (recall Galilei).</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> We are especially enthusiastic about the prospects of combining together the fundamental, the humanistic and the innovation-and-technology related insights.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Notice how our <em>reifications</em> – identifying public informing with what the journalists are doing, and also science, and education, and democracy and... – with their present systemic implementations – is preventing us from seeing them as systems within the larger system of society, and adapting them to the roles they need to perform, and the qualities they need to have – with the help of the new technology. It is not an accident that Benjamin Lee Whorf was one of Doug Engelbart's personal heroes (Doug considered himself "a Whorfian")! There's never an end to discovering beautiful, and subtle, connections. In our prototype portfolio you'll find numerous examples; but let's here zoom in on just a couple of them. </p> | ||

| + | <p>The Club of Zagreb [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] is our redesign of The Club of Rome, based on The Game-Changing Game [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]]. The key point here is to use the insights and the power of the seniors (they are called Z-players) – to empower the young people (the A-players) – to change the systems in which they live and work. </p> | ||

| + | <p> All our answer are, once again, given as [[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] accompanied by an invitation to a conversation through which they will evolve further. By developing those conversations, we'll be seeing <em>and</em> materializing the [[invisible elephant|<em>elephant</em>]]! </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Occupy your university</h3> | ||

| + | <p><blockquote>[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewal </blockquote> | ||

| + | wrote Erich Jantsch. In this way he provided an answer to <em>the</em> key question this conversation is leading us to – Where might this sort of change naturally begin?</p> | ||

| + | <p>Why blame the Wall Street bankers for our condition? Or Donald Trump? Shouldn't we rather see them as <em>symptoms</em> of a social-systemic condition, in which the flow of knowledge is what may bring healing, and solutions. And this flow of knowledge – isn't that really <em>our</em> job?</p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | ----- | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em>Our</em> story</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>How Engelbart's dream came true</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Doug Engelbart passed away on July 2nd, 2013. Less than two weeks later, his desire to see his ideas taken up by an academic community came true! And that community – the International Society for the Systems Sciences – just couldn't have be better chosen.</p> | ||

| + | <p>At this society's 57th yearly conference, in Haiphong Vietnam, this research community began to self-organize according to Engelbart's principles – by taking advantage of new media technology to become "collectively intelligent". And to extend its outreach further into a knowledge-work system, which will connect systemic change initiatives around the world, and help them learn from one another, and from the systems science research. At the conference Engelbart's name was often heard.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>Systemic innovation must grow out of systems science research</h3> | ||

| + | <p>There is a reason why Knowledge Federation remained the [[transdiscipline|<em>transdiscipline</em>]] for [[knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]], why we have not taken up the so closely related and larger goal, of [[bootstrapping|<em>bootstrapping</em>]] the [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]]. If it is to be done properly – and especially if we interpret "properly" in an academic sense – then [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] must grow out of systems science research – which alone can tell us how to understand systems, how to improve them and intervene in them. If we, the knowledge federators, should do our job right, then we must [[knowledge federation|<em>federate</em>]] this body of knowledge, we must not try to reinvent it!</p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"> | ||

| + | <h3>Jantsch's legacy lives on</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Alexander Laszlo was the ISSS President who initiated the mentioned development.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Alexander was practically born into systemic innovation. Didn’t his father Ervin, himself a creative leader in the systems community, point out that our choice was “evolution or extinction” in the very title of one of his books? So the choice left to Alexander was obvious – and he became a promoter and leader of conscious or systemic evolution. </p></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3 round-images">[[File:Laszlo.jpg]]<br><small><center>[[Alexander Laszlo]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <p>Alexander’s PhD advisor was Hasan Özbekhan, who wrote the first 150-page systemic innovation theory, as part of the Bellagio team initiated by Jantsch. He later worked closely in the circle of Bela H. Banathy, who for a period of a couple of decades held the torch of systemic innovation–related developments in the systems community.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>We came here to build a bridge</h3> | ||

| + | <p>As serendipity would have it, at the point where the International Society for the Systems Sciences was having its 2012 meeting in San Jose, at the end of which Alexander was appointed as the society's president, Knowledge Federation was having its presentation of The Game-Changing Game (a generic, practical way to change institutions and other large systems) practically next door, at the Bay Area Future Salon in Palo Alto. (The Game-Changing Game was made in close collaboration with Program for the Future – the Silicon Valley-based initiative to complete Engelbart's unfinished revolution. Doug and Karin Engelbart joined us to hear a draft of our presentation in Mei Lin Fung's house, and for social events. Bill and Roberta English – Doug's right and left hand during the Demo days – were with us all the time.)</p> | ||

| + | <p>Louis Klein – a senior member of the systems community – attended our presentation, and approached us saying "I want to introduce you to some people". He introduced us to Alexander Laszlo and his team.</p> | ||

| + | <p>"Systemic thinking is fine", we wrote in an email, "but what about systemic <em>doing</em>?" "Systemic doing is exactly what we are about", they reassured us. So we joined them in Haiphong.</p> | ||

| + | <p> "We are here to build a bridge", was the opening line of our presentation at the Haiphong ISSS conference, " between two communities of interest, and two domains – systems science, and knowledge media research." The title of the article we brought to the conference was "Bootstrapping Social-Systemic Evolution". We talked about Jantsch and Engelbart who needed each other to fulfill their missions – and never met, in spite of living just across the Golden Gate Bridge from each other. We also shared our views on [[epistemology|<em>epistemology</em>]] and the larger emerging [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]] – and proposed that if the systems research or movement should fulfill its vitally important societal purpose, then it needs to embrace [[bootstrapping|<em>bootstrapping</em>]] or self-organization as (part of) its mode of operation. </p> | ||

| + | <p>If you've seen the short video we shared on Youtube as "Engelbart's last wish", then you'll see how what we did answers to it quite precisely: We realized that systemic self-organization was beginning at a spot in the global knowledge-work system from which it could most naturally scale further; and we joined it, to help it develop further.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Knowledge Federation was conceived by an act of bootstrapping</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Knowledge Federation was initiated in 2008 by a group of academic knowledge media researchers and developers. At our first meeting, in the Inter University Center Dubrovnik (which as an international federation of universities perfectly fitted our later development), we realized that the technology that our colleagues were developing could "make this a better world". But that to help realize that potential, we would need to organize ourselves differently. Our second meeting in 2010, whose title was "Self-Organizing Collective Mind", brought together a multidisciplinary community of researchers and professionals. The participants were invited to see themselves not as professionals pursuing a career in a certain field, but as cells in a collective mind – and to begin to self-organize accordingly. </p> | ||

| + | <p>What resulted was Knowledge Federation as a [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] of a [[transdiscipline|<em>transdiscipline</em>]]. The idea is natural and simple: a trandsdisciplinary community of researchers and other professionals and stakeholders gather to create a systemic [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] – which can be an insight or a systemic solution for knowledge work or in any specific domain of interest. In this latter case, this community will usually practice [[bootstrapping|<em>bootstrapping</em>]], by (to use Alexander's personal motto) "being the systems they want to see in the world". This simple idea secures that the knowledge from the participating domain is represented in the [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] and vice-versa – that the challenges that the [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] may present are taken back to the specific communities of interest and resolved. </p> | ||

| + | <p>At our third workshop, which was organized at Stanford University within the Triple Helix IX international conference (whose focus was on the collaboration between university, business and government, and specifically on IT innovation as its enabler) – we pointed to [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] as an emerging and necessary new trend; and as (the kind of organization represented by) [[knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]] as its enabler. Again the Engelbarts were part of our preparatory activities, and the Englishes were part of our panel as well. Our workshop was chaired by John Wilbanks – who was then the Vice President for Science in Creative Commons.</p> | ||

| + | <p></p> | ||

| + | <p>[[File:BCN2011.jpg]] <br><small><center>Paddy Coulter (director of Oxford Global Media and former director of Oxford University Reuters School of Journalism), Mei Lin Fung (founder of the Program for the Future) and David Price (co-founder of Debategraph and of Global Sensemaking) speaking at our 2011 workshop "An Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism" in Barcelona.</center></small></p> | ||

| + | <p>At our workshop in Barcelona, later that year, media creatives joined the forces with innovators in journalism, to create a [[prototypes|<em>prototype</em>]] for the journalism of the future. </p> | ||

| + | <p>A series of events followed – in which the [[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] shown in Federation through Applications were created.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Knowledge Federation is a federation</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Throughout its existence, and especially in this early period, Knowledge Federation was careful to make close ties with the communities of interest in its own domain, so that our own body of knowledge is not improvised or reinvented but federated. Program for the Future, Global Sensemaking, Debategraph, Induct Software... and multiple other initiatives – became in effect our federation.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The longer story will be told in the book Systemic Innovation (Democracy for the Third Millennium), which will be the second book in Knowledge Federation Trilogy. Meanwhile, we let our portfolio of [[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] presented in Federation through Application tell this story for us.</p> | ||

| + | <p>From the repertoire of [[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] that resulted from this collaboration (see a more complete report in Federation through Applications), we here highlight two.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>The Lighthouse</h3> | ||

| + | <p>It's really the model of the headlights, applied in a specific key domain.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Lighthouse2.jpg]]<br><small><center>The initial Lighthouse design team, at the ISSS59 conference in Berlin where it was formed. The light was subsequently added by our communication design team, in compliance with their role.</center></small> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>If you imagine stray ships struggling on the rough seas of the survival of the fittest competition – then The Lighthouse is showing the way to the harbor of a whole new continent, where the way of working and existing together is collaboration, to create new systems and through them a "better world". </p> |

| + | <p>In the context of the systems sciences, The Lighthouse extends the conventional repertoire of a research community (conferences, articles, books...) into a whole new domain – distilling a single insight for our society at large, which is on the one hand transformative to the society, and on the other hand explains to the public why the research field is relevant to them, why it has to be given far larger prominence and attention than it has hitherto been the case.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>Leadership and Systemic Innovation</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Leadership and Systemic Innovation is a doctoral program that Alexander initiated at the Buenos Aires Institute of Technology in Argentina. It was later accompanied by a Systemic Innovation Lab. The program – the first of its kind – educates leaders capable of being the guides of (the transition to) systemic innovation. </p> | ||

| + | <p>As we have seen, in 1969 Erich Jantsch made a similar proposal to the MIT, but without result. Now the Argentinian MIT clone has taken the torch.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | ----- OLDER --- | ||

| − | + | <div class="page-header" > <h1>Federation through Stories</h1> </div> | |

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 92: | Line 432: | ||

----- | ----- | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *** OLDER *** | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="page-header" > <h1>Federation through Stories</h1> </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p>The first and most important thing you need to know is that what's being presented here is not only or even primarily an idea or a proposal or an academic result. We intend this to be an <em>intervention</em> into our academic and social reality. And more specifically an invitation to a conversation. </p> | ||

| + | <p>And when we say "conversation", we don't mean "just talking". The conversations we want to initiate are intended to <em>build</em> communication in a certain new way, both regarding the media and the manner of communicating, <em>and</em> regarding the themes. We use the [[dialogs|<em>dialog</em>]] – which is a manner of speaking that sidesteps all coercion into a worldview and replaces it by genuine listening, collaboration and co-creation. By conversing in this way we also bring due attention to completely new themes. We evolve a public sphere, or a [[collective mind|<em>collective mind</em>]], capable of thinking new thoughts, and of developing public awareness about those themes. Here in the truest sense the medium is the message.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The details being presented are intended to ignite and prime and energize those [[dialogs|<em>dialogs</em>]]. And at the same time <em>evolve</em> through those [[dialogs|<em>dialogs</em>]]. In this way we want to prime our collective intelligence with some of the ideas of last century's [[giants|<em>giants</em>]], and then engage it to create insights about the themes that matter. </p> | ||

| + | <p>There are at least four ways in which the four detailed modules of this website can be read. </p> | ||

| + | <p>One way is to see it as a technical description or a blueprint of a new approach to knowledge (or metaphorically a lightbulb). Then you might consider | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> Federation through Images as a description of the underlying principle of operation (how electricity can create light that reaches further than the light of fire)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Stories as a description of the suitable technology (we have the energy source and the the wiring and all the rest we need)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Application as a description of the design, and of examples of application (here's how the lightbulb may be put together, and look – it works!)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Conversations as a business plan (here's what we can do with it to satisfy the "market needs"; and here's how we can put this on the market, and have it be used in reality</li> | ||

| + | </ul></p> | ||

| + | <p>Another way is to consider four detailed modules as an Enlightenment or next Renaissance scenario. In that case you may read | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Images as describing a development analogous to the advent of science</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Stories as describing a development analogous to the printing press (which provided the very illumination by enabling the spreading of knowledge)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Applications as describing the next Industrial and technological Revolution, a new frontier for innovation and discovery</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Conversations as describing the equivalent of the Humanism and the Renaissance (new values, interests, lifestyle...)</li> | ||

| + | </ul></p> | ||

| + | <p>The third way to read is to see this whole thing as a carefully argued <em>case</em> for a new [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]] in knowledge work. Here the focus is on (1) reported anomalies that exist in the old [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]] and how they may be resolved in the new proposed one and (2) a new creative frontier, that every new [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]] is expected to open up. Then you may consider | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Images as a description of the fundamental anomalies and of their resolution</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Stories as a description of the anomalies in the use and development of information technology, and more generally of knowledge at large</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Applications as a description or better said of a map of the emerging creative frontier, showing – in terms of real-life [[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] what can be done and how</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Conversations as a description of societal anomalies that result from an anomalous use of knowledge – and how they may be remedied</li> | ||

| + | </ul></p> | ||

| + | <p>And finally, you may consider this an application or a showcase of [[knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]] itself. Naturally, we'll apply and demonstrate some of the core technical ideas to plead our case. You may then read | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Images as a description and application of [[ideograms|<em>ideograms</em>]] – which we've applied to render fundamental-philosophical ideas of giants accessible, and in effect create a cartoon-like introduction to a novel approach to knowledge</li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Stories brings forth [[vignettes|<em>vignettes</em>]] – which are the kind of interesting, short real-life stories one might tell to a party of friends over a glass of wine, and which enable one to "step into the shoes of a giant" or "see through his eyeglasses" </li> | ||

| + | <li>ALT </li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Applications as a portfolio of [[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] – a characteristic kind of results that suit the new approach to knowledge – which in [[knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]] serve as (1) models (showing how for ex. education or journalism may be different, who may create them and how), (2) interventions ([[prototypes|<em>prototypes</em>]] are embedded in reality and acting upon real-life practices aiming to change them) and (3) experiments (showing us what works and what doesn't).<li> | ||

| + | <li>Federation through Applications as a small portfolio of [[dialogs|<em>dialogs</em>]] – by which the new approach to knowledge is put to use</li> | ||

| + | </ul></p> | ||

| + | <h3>Highlights</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Instead of providing you an "executive summary", which would probably be too abstract for most people to follow, we now provide a few anecdotes and highlights, which – we feel – will serve better for mobilizing and directing your attention, while already extracting and sharing the very essence of this presentation. As always, we'll use the ideas of [[giants|<em>giants</em>]] as 'bread crumbs' to mark the milestones in our story or argument.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h3>Social construction of truth and meaning</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Sixty years ago, in "Physics and Philosophy", [[Werner Heisenberg]] explained how | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | the nineteenth century developed an | ||

| + | extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not | ||

| + | only science but also the general outlook of great masses of | ||

| + | people. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | He then pointed out how this frame of concepts was too narrow and too rigid for expressing some of the core elements of human culture – which as a result appeared to modern people as irrelevant. And how correspondingly limited and utilitarian values and worldviews became prominent. Heisenberg then explained how modern physics disproved this "narrow frame"; and concluded that | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of | ||

| + | concepts of the nineteenth century. | ||

| + | </blockquote></p> | ||

| + | <p>If we now (in the spirit of [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]], and the emerging [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]]) consider that the social role of the university (as institution) is to provide good knowledge and viable standards for good knowledge – then we see that just this Heisenberg's insight alone gives us an <em>obligation</em> – which we've failed to respond to for sixty years.</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3 round-images"> [[File:Heisenberg.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Werner Heisenberg]]<br>the icon of [[design epistemology]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <p>The substance of Federation through Images is to show how <em>the fundamental insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy allow us to develop a way out of "the rigid frame" </em> – which is a rigorously founded methodology for creating truth and meaning about any issue and at any level of generality, which we are calling [[polyscopy|<em>polyscopy</em>]]. You may understand [[polyscopy|<em>polyscopy</em>]] as an adaptation of "the scientific method" that makes it suitable for providing the kind of insights that our people and society need, or in other words for [[knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]]. In essence, [[polyscopy|<em>polyscopy</em>]] is just a generalization of the scientific approach to knowledge, based on recent scientific / philosophical insights – as we've already pointed out by talking about [[design epistemology|<em>design epistemology</em>]], which is of course the epistemological foundation for [[polyscopy|<em>polyscopy</em>]]. </p> | ||

| + | <h3>Information technology</h3> | ||

| + | <p>You may have also felt, when we introduced [[knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]] as 'the light bulb' that uses the new technology to illuminate the way, that we were doing gross injustice to IT innovation: Aren't we living in the Age of Information? Isn't our information technology (or in other words our civilization's 'headlights') indeed <em>the most modern</em> part of our civilization, the one where the largest progress has been made, the one that best characterizes our progress? In [[STORIES|Federation through Stories]] we explain why this is not the case, why the candle headlights analogy works most beautifully in this pivotal domain as well – by telling the story of Douglas Engelbart, the man who conceived, developed, prototyped <em>and demonstrated</em> – in 1968 – the core elements of the new media technology, which is in common use. This story works on many levels, and gives us a <em>textbook</em> example to work with when trying to understand the emerging [[paradigm|<em>paradigm</em>]] and the paradoxical dynamics around it (notice that we are this year celebrating the 50th anniversary of Engelbart's demo...).</p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | Digital technology could help make this a better world. But we've also got to change our way of thinking. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | These two sentences were (intended to be) the first slide of Engelbart's presentation of his vision for the future of (information-) technological innovation in 2007 at Google. We shall see that this 'new thinking' was precisely what we've been calling [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]]. Engelbart's insight is so central to the overall case we are presenting, that we won't resist the urge to give you the gist of it right away.</p> | ||