STORIES

Contents

- 1 Federation through Stories

Federation through Stories

Information technology and contemporary needs

Liberating and directing creative work

On our main page we suggested that when we liberate our creative work in general, and our knowledge work in particular, from subservience to age-old patterns and routines and outmoded assumptions, and then motivate it and orient it differently, a sweeping Renaissance– like change may be expected to result. We motivated this observation, and our initiative, by three large changes that took place during the past century – of epistemology, of information technology, and of our society's condition and information needs. In Federation through Images we took up the first motive. Here our theme will be the remaining two.

In Federation through Images we used the image of a bus with candle headlights to make a sweepingly large claim: When innovation (or creative work in general) is "knowledge-based" and so directed as to improve or complete the larger whole in which what is being innovated has a role, then the difference this may make, the benefits that may result to our society, are similar as the benefits of substituting light bulbs for candles may be to the people in that bus.

There is, however, an obvious alternative – and that is what is in effect today. Two alternatives, to be exact. In academic research, we insist on using the inherited ways of creating knowledge – even if they might be 'candles'; and in technological innovation we simply aim to maximize profit, and trust that "the invisible hand" of the market will turn that into common good (or that the 'bus' in which we are riding into the future will be safe and sound and secure that we'll continue living in the best of all possible worlds. The real-life stories we are about to tell will help us make a case for a more up-to-date alternative.

The nature of our stories

Our stories illustrate a larger point

We choose our stories to serve as parables. In a fractal-like manner, each of them will reflect – from a specific angle, of course – the entire situation our creative work and specifically knowledge work is in. So just as the case was with our ideograms, our stories too can be worth one thousand words. They too can condense and vividly display a wealth of insight. Bring to mind again the iconic image of Galilei in house prison, whispering eppur si muove. The stories we are about to tell might suggest that also in our own time similar situations and dynamics are at play.

How to lift up an idea of a giant

The stories we'll tell, which are technically called vignettes, are also part of our technical portfolio. They'll help us lift up core insights of giants from undeserved anonymity. vignettes are engaging, lively, catchy, sticky... real-life people and situation stories, the kind of thing one might want to tell to an assembly of friends over a glass of vine. Their role is to distill core ideas of daring thinkers from the vocabulary of their field, and turn them into interesting subjects of conversation. And thereby also, of course, give them the power of impact.

By joining vignettes together into threads, and threads into patterns and patterns into a gestalt – we can create an overarching view of our situation, which shows how the situation may (need to) be handled.

The incredible history of Doug

How the Silicon Valley failed to hear its giant in residence

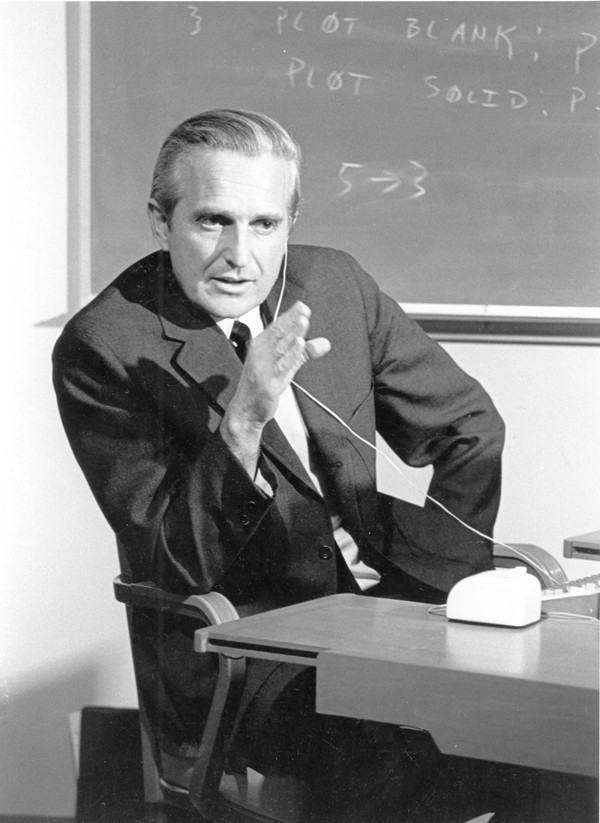

Before we go into the details of this story, take a moment to see how it works as a parable. The story is about how the Silicon Valley failed to understand and even hear its giant or genius in residence, even after having recognized him as such! This makes the story emblematic: The Silicon Valley is the world's hottest innovation hub. Are those people there smart? Exceptionally so, there can be no doubt about that! So this story will both serve to point to a new direction, that is, to the elephant – which is what Doug was trying to do to the Valley (just look at his photo and you'll see that). The fact that the Valley ignored him will serve as a warning to the rest of us – and an invitation to look deeper into this matter

How it all began

Having decided, as a novice engineer in December of 1950, to direct his career so as to maximize its benefits to the mankind, Douglas Engelbart thought intensely for three months about the best way to do that. Then he had an epiphany.

On a convention of computer professionals in 1968 Engelbart and his SRI-based lab demonstrated the computer technology we are using today – computers linked together into a network, people interacting with computers via video terminals and a mouse and windows – and through them with one another.

In the 1990s it was finally understood (or in any case some people understood) that it was not Steve Jobs and Bill Gates who invented the technology, or even the XEROS PARC, from where they took it. Engelbart received all imaginable honors that an inventor can have. Yet he made it clear, and everyone around him knew, that he felt celebrated for a wrong reason. And that the gist of his vision had not yet been understood, or put to use. "Engelbart's unfinished revolution" was coined as the theme for the 1998 Stanford University celebration of his Demo. And it stuck.

The man whose ideas created "the revolution in the Valley" passed away in 2013 – feeling he had failed.

How it all ended

What was it that Engelbart saw in his vision, and pursued so passionately throughout his long career? What was it that people around him could not see? We'll answer by zooming in on one of the many events where Engelbart was celebrated, and when his vision was in the spotlight – a videotaped panel that was organized for him at Google in 2007. This will give us an opportunity to explain his vision – if not in his own words, then at least with his own Powerpoint slides. Here is how his presentation was intended to begin.

Around that time it became clear that Engelbart's long career was coming to an end. By choosing title "A Call to Action!", Engelbart obviously intended make it clear that what he wanted to give to Google, and to the world through Google, was a direction and a call to pursue it.

The first slide pointed to a large and as yet unfulfilled opportunity that is immanent in digital technology. The digital technology can help make this a better world! But to realize this potential of technology, we need to change our way of thinking.

The second slide was meant to explain the nature of this different thinking, and why we needed it. The slide points to a direction. Doug talks about a 'vehicle' we are riding in. You'll notice that part of the message here is the same as in our Modernity ideogram, which we discussed at length in Federation through Images. But there's also more; the vehicle has inadequate "steering and braking controls".

The third slide was there to point to way to remedy this problem. To set the stage for explaining the essence of Doug's vision; for understanding the purpose and the value of his many technical ideas and contributions (which is what the remainder of the slides were about); and ultimately for making his call to action.

But let's wait with this third slide. Before we talk about the solution, let's first make sure we understand what the problem is.

We shall come to this story and continue it in just a moment. But before we do that, we shall do a bit of 'connecting the dots' around Doug's framing of the problem, in his second slide.

Unsustainable by design

Worse than a dictatorship

So let us now look at Doug's second slide from an angle that is familiar to everyone – democracy. In the old ( and still so stubbornly dominant) traditional order of things, democracy is the set of processes and institutions that we associate with this word. As long as we have the constitution and the elections and the press are free, it is assumed, we have democracy. We the people are in control. The nightmare scenario in this order of things is a dictatorship, where a dictator has taken from the people those affordances of control and tokens of freedom.

But what Doug was pointing to is another, much worse nightmare scenario – where nobody has control! Where the "vehicle" in which we are riding into the future lacks the structure (or metaphorically suitable "headlights" and "steering and braking") that would make it controllable. A dictator may come to his senses. His more reasonable son may succeed him. The generals or the people may make a coup. But if the system as a whole is not controllable by design – then we really have a problem!

The science of control

A scientific reader may have noticed that Engelbart's seemingly innocent metaphor in Slide 2 has a technical-scientific interpretation. In cybernetics, which is a scientific study of (the relationship between information and) control, "feedback" and "control" are household terms. Just as the bus must have functioning headlights and steering and braking controls, so must any system have suitable feedback (inflow of suitable information), and suitable control (a way to apply the incoming information to correct its course or functioning or behavior) – if it is to be steerable or viable or "sustainable".

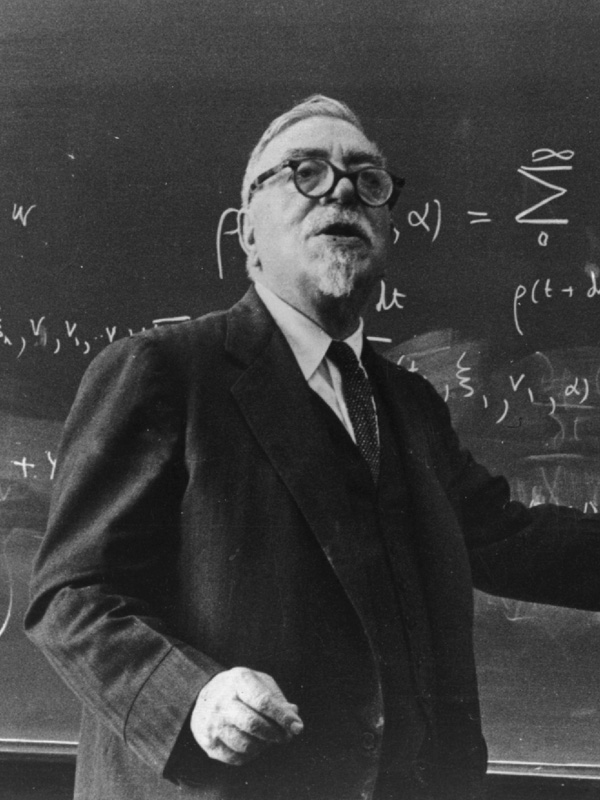

Norbert Wiener might be a suitable iconic giant to represent (the vision that inspired) cybernetics for us. He was recognized as a potential giant already as a child. So he studied mathematics, zoology and philosophy, and finally got his doctorate in mathematical logic from Harvard – when he was only 17! Then he went on to do seminal work in a number of fields – one of which was cybernetics.

We'll represent Wiener here with the final chapter of his 1948 book Cybernetics, titled "Information, Language and Society'." We'll briefly – as briefly as we are able without spoiling the story – highlight two pints from this chapter, two dots to connect, in two brief sections. We'll mention two more giant on whose shoulders he was standing. Here's the first one.

The feedback is broken

The first of the Wiener's two key insights we'll point to is that our communication, or our society's "feedback", is dysfunctional and must be rebuilt.

Wiener cites Vannevar Bush, who was his MIT colleague and twice his boss (first as the MIT dean, and then as the leader of the U.S. WW2 scientific effort), to make this point. And since Bush also inspired Engelbart, and since he's a suitable icon giant for this most central point, it's time that we introduce him here properly with a brief story and a photo. <p>Vannevar Bush was the giant who most vividly and from an authoritative position pointed to the urgent need for (what we are calling) knowledge federation – already in 1945!

A pre-WW2 pioneer of computing machinery, and professor and dean at the MIT, During the war Bush served as the leader of the entire US scientific effort – supervising about 6000 leading scientists, and assuring that the Free World is a step ahead in developing all imaginable weaponry including The Bomb. And so in 1945, the war just barely being finished, Bush wrote an article titled "As We May Think", where the tone is "OK, we've won the great war. But one other problem still remains to which we scientists now need to give the highest priority – and that is to recreate what we do with knowledge after it's been published". He urged the scientists to focus on developing suitable technology and processes.

Engelbart heard him. He read Bush's article in 1947, as a young army recruit, in a Red Cross library in the Philippines, and it helped him 'see the light' a couple of years later. But Bush's article inspired in part also another development – and that's what we'll turn to next.

The market won't give us control

There is an obvious alternative to all this – the market! The free competition. The belief that we don't really need headlights, that we don't really need knowledge federation and systemic innovation – that all we need to do is worry about "our own" interests, and "the invisible hand" of the market will secure that everything is for the better in the best of all worlds. Wiener's second insight is that there is no "invisible hand" to rely on; that we must do the work we were relegating to it ourselves. Listen for a moment to Wiener's tone. Is it suggesting that some deep and power-related prejudices are at play (recall Galilei...):

The "homeostatic process" here is what we've been calling "feedback-and-control". It's been defined as "feedback mechanism inducing measures to keep a system continuing".There is a belief, current in many countries, which has been elevated to the rank of an official article of faith in the United States, that free competition is itself a homeostatic process: that in a free market, the individual selfishness of the bargainers, each seeking to sell as high and buy as low as possible, will result in the end of a stable dynamics of prices, and with redound to the greatest common good. This is associated with the very comforting view that the individual entrepreneur, in seeking to forward his own interest, is in some manner a public benefactor, and has thus earned the great reward with which society has showered him. Unfortunately, the evidence, such as it is, is against this simple-minded theory.

Wiener made a transition most interesting for us – between the first of the above insights to the second. He did that by pointing to the work of another giant whose essential message was ignored. His point was "See this really central insight that my distinguished colleague found out, and yet he found himself ignored – truly our communication doesn't work!" The giant was John von Neumann, whose many seminal contributions include the design of the first digital computer – and (with Morgenstern) the game theory, which is what Wiener was talking about.

Let's add to Wiener's observation that the research on a specific theme that interests us most here virtually exploded in the 1950s – i.e. after Cybernetics was published, resulting in more than one thousand research articles. The theme is popularly known as "prisoner's dilemma". All we'll need from this research here, however, is once again the most simple fact this research stands for – that it may be the case that rational self-service (exact, mathematical maximization of one's own gains) brings all players to an outcome that is inferior to what they would achieve had they collaborated. The point here is that collaboration may lead to a win-win situation; competition may lead to a lose-lose situation!

We don't need to go into details. Our theme here is perhaps the core belief, which is as germane to our contemporary condition as the unquestionable reliance on the scriptures was five centuries ago – the belief that we don't really need to team up and collaborate and build a better world (or systems); that all we really need is to do is to play competitively within the existing systems. If we agree (make a convention) that religion is the ethical fiber of the society – what binds each of us to a purpose and all of us into a society – then this qualifies as our contemporary religion.

The alternative is what Wiener was establishing, and arguing for – cybernetics. If we cannot trust the market, then what can we trust? We need suitable information to show us how to evolve and steer our systems, and our society or democracy at large. We can develop that information through a scientific study of natural and man-made systems, and abstracting from them to create general insights and rules. That's of course what cybernetics is about. You may now begin to understand knowledge federation / systemic innovation as the next step in the same direction. The details will follow.

Democracy 2.0

Toward an informed approach to contemporary issues

"We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them," said Einstein. Systemic thinking offers itself as a natural or informed alternative. And if we follow this alternative for just one step, if we begin to apply it – as we just did – then Einstein's most famous word of wisdom can be paraphrased as "We cannot solve our problems with the same systems we used when we created them." If you are still frowning, more evidence will be provided; and an invitation to resolve the remaining hesitancies in a conversation.

If, however, you are ready to join us in exploring this possibility, then you might already anticipate, perhaps with trepidation, the possibility of reducing all our problems, with all their "wickedness" and complexity, to a single and straight-forward challenge – of updating our systems!

You might then have no difficulty understanding why we are talking about democracy: If we the people should really be in control, and if suitable controls presently don't even exist, then the very first thing our democracy must be able to do to still merit that name is to develop the capability to recreate itself, that is, its own systems. Or more generally, to recreate 'our games', instead of confining us to playing competitively within them.

The science behind innovation

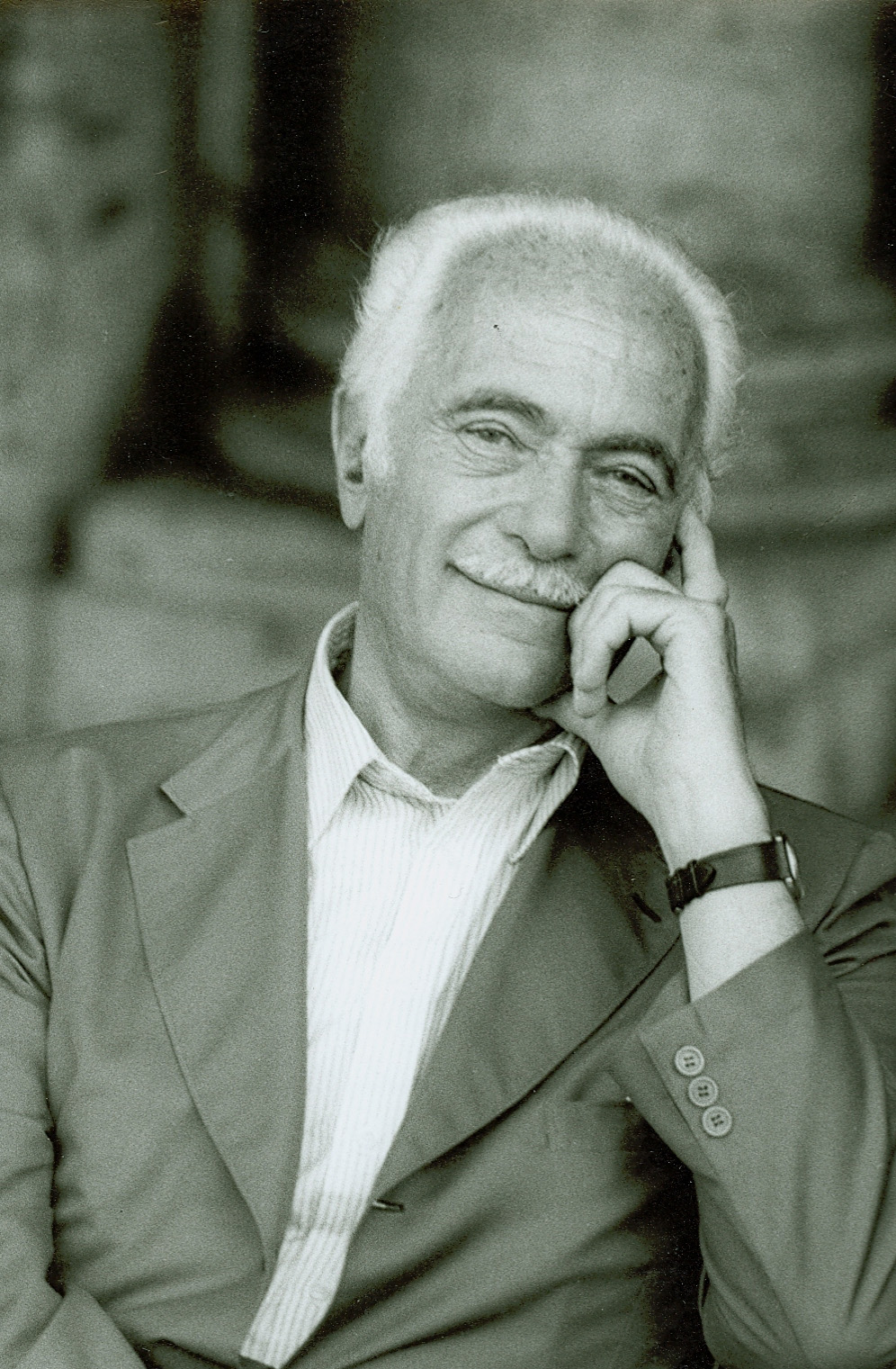

Having received his doctorate in astrophysics at the tender age of 22, from the University of Vienna, Erich Jantsch realized that it is here on Earth that his attention is needed. And so he ended up researching, for the OECD in Paris, the theme that animates our initiative (how our ability to create and induce change can be directed far more purposefully and effectively). Jantsch's specific focuse was on the ways in which technology was being developed and introduced in different countries, the OECD members. Jantsch and the OECD called this issue "technological planning". Is it only the market? Or is there some way we can more effectively direct the development and use of the rapidly growing muscles of our technology?

So when The Club of Rome (a global think tank, consisting of 100 selected international and interdisciplinary members, organized to do research on the future prospects of mankind, and if the situation demands it also intervene) was about to be initiated, in 1968, it was natural to invite Jantsch to give the opening keynote.

Immediately after the opening of The Club of Rome Jantsch made himself busy crafting solutions. By following him through three steps of this process, we shall be able to identify three core insights, three pieces in our 'elephant puzzle', which we owe to Jantsch.

But before we do that, let's put on our map Aurelio Peccei, the giant whose keen insight and resolute initiative made The Club of Rome and its various achievements and insights possible.

We must find a way to change course

"The human race is hurtling toward a disaster. It is absolutely necessary to find a way to change course", Aurelio Peccei (the co-founder, firs president and the motor power behind The Club of Rome) wrote this in 1980, in One Hundred Pages for the Future, based on this think tank's first decade of research.

Peccei was an unordinary man. During the WW2 he was captured by the Gestapo and tortured for six months, without revealing his contacts. He later wrote that he was grateful for this experience because it formed him. Peccei was also an uncommonly able and successful business leader. While serving as the director of Fiat's operations in Latin America, where the cars were not only sold but also produced, he established Italconsult, a consulting and financing agency to help the development of the Third World countries. When the Italian technological giant Olivetti was in trouble, Peccei was brought in as the president; he managed to bring Olivetti up again. And yet the question that most intensely preoccupied Peccei was still much larger than the ones just mentioned – the nature of our civilization's condition, and how this condition was changing.

Here is one of the ways in which Peccei later framed the answer (in 1977, in The Human Quality, his personal reflections on the human condition and his recommendation for handling it):

Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world.

Planning as feedback, systemic innovation as control

With a doctorate in physics, it was not difficult to Jantsch to put two and two together and se what needed to be done. If our civilization is on a disastrous course, the reason must be that (as Engelbart put it) the "headlights and braking and steering controls) we have inherited from the past no longer serve their most central purpose. So let's then waste no time, let's get busy creating new ones! Right after The Club of Rome meeting Jantsch gathered a group of creative leaders and systemic thinkers and researchers in Bellagio, Italy, to co-create a draft. The result was so basic that Jantsch called it "rational creative action". The message is obvious and central to our interest: Certainly there are many ways in which one can be creative. But if our creative action is to be rational – then these essential ingredients must be present in it.

Rational creative action begins with forecasting, which explores different future scenario; it ends with an action selected to enhance the likelihood of the desired scenario or scenarios. A key role is played by a new social process they called "planning" (notice that this had nothing to do with the kind of planning that was at the time used in the Soviet Union):

[T]he pursuance of orthodox planning is quite insufficient, in that it seldom does more than touch a system through changes of the variables. Planning must be concerned with the structural design of the system itself and involved in the formation of policy.”

Policies, which are the objective of planning (as the authors of the Bellagio Declaration envisioned it) specify both the institutional changes and the norms and value changes that might be necessary to make our goal-oriented action in a true sense rational and creative (Jantsch, 1970):

Policies are the first expressions and guiding images of normative thinking and action. In other words, they are the spiritual agents of change—change not only in the ways and means by which bureaucracies and technocracies operate, but change in the very institutions and norms which form their homes and castles.”

The emerging role of the university

The next question in Jantsch's stream of thought and action was roughly this: If "rational creative action" is a necessary new capability that our systems and our civilization at large now require, then who – that is, what institution – may be the most natural and best qualified to foster this capability? Jantsch concluded that the university (institution) will have to be the answer. And that to be able to fulfill this role, the university itself will need to update its own system.

[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewal. It may have to become a political institution, interacting with government and industry in the planning and designing of society’s systems, and controlling the outcomes of the introduction of technology into those systems. This new leadership role of the university should provide an integrated approach to world systems, particularly the ‘joint systems’ of society and technology.”In 1969 Jantsch spent a semester at the MIT, writing a 150-page report about the future of the university, from which the above excerpt was taken, and lobbying with the faculty and the administration to begin to develop this new way of thinking and working in academic practice.

Evolution is the key

In the 1970s Jantsch lived in Berkeley, wrote prolifically, and taught occasional seminars at the U.C. Berkeley. This period of his life and work was marked by a new insight, which was triggered by his experiences with working on global / systemic change, and some profound scientific insights brought to him, initially, by Ilya Prigogine, the Nobel laureate scientist who visited Berkeley in 1972. Put very briefly, this involves two closely related insights:

- we cannot – that is, nobody can – recreate the large systems including the largest, our civilization, in any way directly; where we can make a difference – and hence where we must focus on – is their evolution;

- the living and evolving systems are governed by an entirely different dynamic than physical systems – which needs to be understood</p> <p>Jantsch was especially interested in understanding the relationship between our that is, people's values and ways of being, and our evolution. He saw us as entering the "evolutionary paradigm". The title of his 1975 book "Design for Evolution" points unequivocally toward the same direction that we tried to frame with our four keywords. Specifically systemic innovation we adopted directly from Jantsch.

Engelbart's unfinished revolution

What Engelbart saw

What is it that Engelbart saw? Why was this not understood? How important is it? We are now ready to answer those questions by revisiting the first three slides prepared for his 2007 call to action at Google. This story will serve two roles: (1) we'll share a not-yet-understood life-changing insight of a giant; (2) the way his insight was handled – or mishandled – by the world's leading IT innovation incubator (the Silicon Valley) will serve as an experiment offering the resolution to our core issue (should innovation / creative work be informed / systemic – or should we rely on free competition / the market). We will then have a story-book confirmation of the basic wisdom that we introduced in Federation through Images with the help of the Modernity ideogram (bus with candle headlights image) – namely that while innovation that aims at systemic wholeness will now make quite literally a world of difference, we are still in the habit of inheriting "the candles" and ignoring that opportunity.

The 20th century printing press

The printing press is a suitable metaphor for us here. Gutenberg's invention is often mentioned as a major factor that led to the Enlightenment – by making knowledge sharing incomparably more efficient. What technology might play a similar role today?

"The answer is obvious", we imagine you think, "It's the Web!" "Of course it's the Web", we'll let Engelbart answer, by his very first slide "but we also have to change the way we think!" Doug's second slide explained what this new way of thinking is about. And we explored its scientific roots through cybernetics and The Club of Rome work.

Engelbart's epiphany

The third slide will allow us to explain the crux of Engelbart's vision. Let's look closer at each of its three paragraphs.

The first paragraph sets the stage for Doug's core discovery.

Many years ago I dreamed that digital technology could greatly augment our collective human capabilities for dealing with complex, urgent problems.Doug's motivation was that – as he explained in his second slide – our civilization is rushing into the future at an accelerating speed. What we the people need above all is a way to deal with complex and urgent issues. To Doug this factor – complexity times urgency – was the core challenge, and what was to be tackled by "augmenting our collective intelligence".

The second paragraph frames the core of Engelbart's vision, and contribution.

Computers, high-speed communications, displays, interfaces—as if suddenly, in an evolutionary sense, we are getting a super new nervous system to upgrade our collective social organisms."A super new nervous system!" The reference here is to the completely new capability that the new media technology affords us. Doug called it CoDIAK (Concurrent Development, Integration and Application of Knowledge). The point is in the word "concurrent". We are linked together in such a way that we can think together and create together – as if we were nerve cells in a single organism. You put something on the Web and instantly anyone in the world can see it! People can be subscribed and be notified. You may have a question – someone else may have an answer... Compare this to the printing press – which could only vastly speed up what the people (the scribes, or the monks in the monasteries) were already doing – copying manuscripts. But the principle of operation remained the same – publishing! But when we are all connected to each other through interactive media technology – completely new processes become possible. And as we shall see – also necessary!

To see how this may help us deal with complexity and urgency of problems, imagine your own organism going toward a wall. (You may think this matter is simple – but we know scientifically that there is some quite complex processing of sensory data that leads to this gestalt.) Imagine now that your eyes see that something is wrong, but are trying to communicate it to the brain by publishing research articles in some specialized field of science. Imagine furthermore that the cells in your nervous system have not specialized and organized themselves to make sense of impulses, filter out the less relevant ones... Imagine that everyone in your body is using the nervous system to merely broadcast information! Would you be confused? Well that's exactly the condition in which the development of information technology has brought us to.

The third paragraph points to the unfulfilled part, which remained only a dream.

I dreamed that people could seriously appreciate the potential of harnessing the technological and social nervous system to improve the collective IQ of our various organizations.Technological and social nervous system. Doug never tired of emphasizing that what the technology does and what the people do must evolve together. And that progress of the "tools system" has not been paralleled with a similar progress of the "human system".

Engelbart's legacy

The meaning and the value of everything that Engelbart created, or dreamed of, must be understood in the context just presented.

Even the technical pieces that he received the credit for, the interactive user interface, collaboration on a distance... Doug experimented with linking people together in a seamless way. With a mouse in the right hand and the chorded keyset in the left, and the eyes fixed on the screen – one does not even need to move his hands to do most of the instant processing...

Similarly the Open Hyperdocument System, which was the design philosophy underlying the NLS system that was demonstrated in 1968. People thinking together will not necessarily create... old-fashioned books and articles! Why not let the new hypermedia documents freely evolve, or even better, be loose conglomerations of a variety of media pieces, assembled together according to need... But the Word and the Powerpoint and the email and the Photoshop... – they are all just reproducing the processing of the pre-Web kind of documents. Each in its own document format, not interoperable... Can't create new workflows!

And then there are higher-level constructs, quite a few of them. Let's just mention a couple: the Networked Improvement Community (NIC) is a basic new socio-technical system for a (generic) discipline – the B-level improvement activity... But there's another, C level – improving the improvers, organized as a NIC of NICs. But that's exactly what we are calling the transdiscipline; and that's quite precisely what the cybernetics, and the systems sciences, are about.

It is most interesting in the larger context we are exploring to see that Engelbart developed an original methodology for systemic innovation – already in 1962, i.e. six years before the systems scientists did that in Bellagio! The methodology is based on "augmentation system"... (explain?)

The incredible part

There are several points that make this history of Doug in a true sense incredible. The first one is that he had this epiphany already in 1951, when there were only a handful of computers in the world, and (practically) nobody had seen one. Those computers were gigantic monsters made out of old-fashioned radio tubes; and they served exclusively for scientific calculations in large labs such as Los Alamos. At that point Doug saw people linked to computers via interactive video terminals, and through computers to each other, through an interactive network.

The other incredible point is that he tried for more than a half-century to explain his insight to the Silicon Valley – and failed!

The unfinished part

Engelbart was quite clear that it was a paradigm that he was struggling against. When in the early 1990s he taught the "Bootstrap Seminar" to share his ideas and initiate their implementation, he would begin by talking about the historical paradoxical responses to emerging paradigms. (An example was IBM's Thomas Watson's prediction that "there is a world market for about five computers".) He would then ask the participants to discuss paradigm-related mishaps and challenges in pairs. Then he would talk more about paradigms.

Engelbart also saw an original solution to the Wiener's paradox. He called it bootstrapping. The point is to not (only) tell the world how the systems should be, but engage in re-creating systems hands-on. Typically, but not exclusively, this is achieved when the developers of the system use themselves as the initial human part of the system. This idea was the core of Doug's all action in the last two decades of his career. When in the late 1980s he and his daughter Christina created an institute to share his gift to the world, the institute was first called "Bootstrap Institute", and it was later renamed "Bootstrap Alliance". The idea is clear – to bootstrap, the key will be to create alliances with businesses and universities and other institutions, and bootstrapping the systemic change together with them.

Wiener's paradox

Publishing had no effect

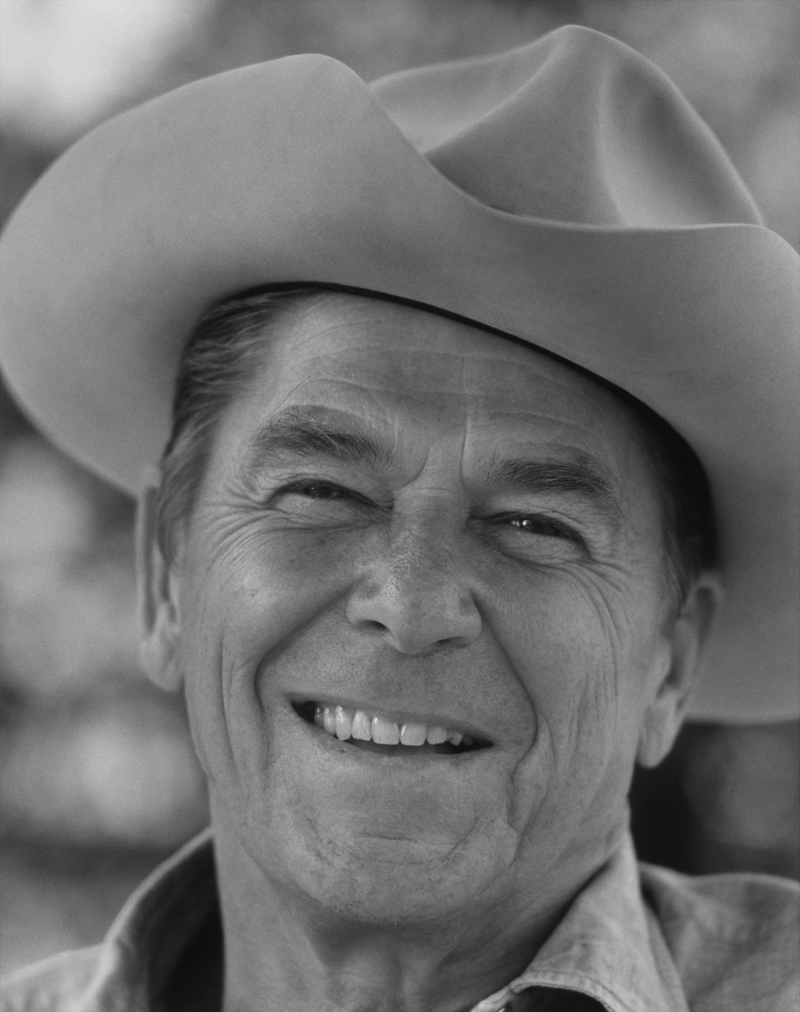

Ronald Reagan is not presented here as one of the giants, but as a person who none the less can open up our eyes to the nature of our situation, and of the emerging paradigm, perhaps even a lot better than the words of the more visionary people may. In the 1980 – when Erich Jantsch passed away at the tender age of 51 (an obituary mentioned malnutrition as a possible cause...), having just issued two books about the "evolutionary paradigm" in science and in our understanding and handling of systems, Ronald Reagan became the 40th U.S. president on a clear agenda: We can only trust the market! The moment we begin to interfere with its perfect mechanisms, we are asking for trouble.

The point here is not whether he was right or wrong, but the lack of knowledge federation. The words of our giants just simply had no effect on how the votes were cast – and how the world ended up being steered!

What we have is a paradox

"As long as a problem is treated as a paradox, it can never be resolved,...". What we have is not a problem, it's a paradox! To see that, notice that Norbert Wiener etc.

In 2015 we presented an abstract and talk titled "Wiener's paradox – we can resolve it together" to the 59th conference of the International Society for the Systems Sciences. The point was.

The solution is bootstrapping

The alternative – we must BE the systems! Engelbart - bootstrapping. Jantsch - action! Our design epistemology...

Doug's last wish...

The future has already begun

Be the systems you want to see in the world

Fortunately, our story has a happy ending. (...)

Less than two weeks after Douglas Engelbart passed away – on July 2, 2013 – his dream was coming true in an academic community. AND the place could not be more potentially impactful than it was! As the President of the ISSS, on the yearly conference of this largest organization of systems scientists, which was taking place in Haiphong, Vietnam, Alexander Laszlo initiated a self-organization toward collective intelligence.

He really had two pivotal ideas. One was to make the community intelligent. The other one was to make an intelligent system for coordinating change initiatives around the globe. (An extension of).

Alexander was practically born into this way of thinking and working. His father...

We came to build a bridge

We came to Haiphong with the story about Jantsch and Engelbart; and with the proposal "We are here to build a bridge"...

And indeed – the bridge has been built! The two initiatives have federated their activities most beautifully!

Prototypes include LaSI SIG & PHD program, the SIL... And The Lighthouse project, among others.

The meaning of The Lighthouse (although it belongs really to prototypes, and to Applications): It breaks the spell of the Wiener's paradox. It creates a lighthouse, for the systems community, to attract stray ships to their harbor. It employs strategic - political thinking, systemic self-organization in a research community, and contemporary communication design, to create impactful messages about a single issue, and placing them into the orbit: CAN WE TRUST "THE MARKET"? or do we need systemic understanding and innovation and design?

Innovation 2.0

The system

As Doug said – it's just to change our way of thinking!

We gave our design team what might be the challenge of our time – to make this design object palpable and clear to people. The above System ideogram is what they came up with.

We let this ideogram stand for this key challenge – to help people see themselves as parts of larger systems. To see how much those systems influence our lives. And to perceive those systems as our, that is human creations – and see that we can also re-create them!

Changing scales

Polyscopy as a methodology in knowledge creation and use has an interesting counterpart in systemic innovation as we are presenting it here. Yes, we have been focused so much on the details, that we completely neglected the big picture. But information – and also innovation, of course – exist on all levels of detail! Should we not make sure that the big picture is properly in place, that we have the right direction, or that the large system is properly functioning, before we start worrying about the details?

The next industrial revolution?

So forget for a moment all that has been said here. This is not about the global issues, or about information technology. We are talking about something far larger and more fundamental. Think about "the systems in which we live and work", as Bela H. Banathy framed them. Imagine them as gigantic machines, which we are of course part of. Their function is to take our daily work as input, and produce socially useful output. Do they? How well are they constructed? Are they wasting our daily work, or even worse – are they using it against our best interests?

See

Evangelizing systemic innovation.

The emerging societal paradigm is often seen as a result of some specific change, for example to "the spiritual outlook on life", or to "systemic thinking". A down-on-earth, life-changing insight can, however, more easily be reached by observing the stupendous inadequacy of our various institutions and other systems, and understanding it as a consequence of our present values and way of looking at the world. The "evangelizing prototypes" are real-life histories and sometimes fictional stories, whose purpose is to bring this large insight or gestalt across. They point to uncommonly large possibilities for improving our condition by improving the systems. A good place to begin may be the blog post Ode to Self-Organization – Part One, which is a finctional story about how we got sustainable. What started the process was a scientist observing that even though we have all those incredible time-saving and labor-saving gadgets – we seem to be more busy than the people ever were! What happened with all that time we saved? (What do you think...?) Toward a Scientific Understanding and Treatment of Problems is an argument for the systemic approach that uses the metaphor of scientific medicine (which cures the unpleasant symptoms by relying on its understanding of the underlying anatomy and physiology) to point to an analogous approach to our societal ills. The Systemic Innovation Positively recording of a half-hour lecture points to some larger-than-life benefits that may result. The already mentioned introductory part (and Vision Quest) of The Game-Changing Game is a different summary of those benefits. The blog post Information Age Coming of Age is the history of the creation and presentation (at the Bay Area Future Salon) of The Game-Changing Game, which involves Doug Engelbart, Bill and Roberta English and some other key people from the Engelbart's intimate community.

Evangelizing knowledge federation.

The wastefulness and mis-evolution of our financial system is of course notorious. Yet perhaps even more spectacular examples of mis-evolution, and far more readily accessible possibilities for contribution through improvement, may be found in our own system – knowledge-work in general, and academic research, communication and education in particular. (One might say that the bankers are doing a good job making money for the people who have money...) That is what these evangelizing prototypes for knowledge federation are intended to show. On several occasions we began by asking the audience to imagine meeting a fairy and being approached by (the academic variant of) the usual question "Make a wish – for the largest contribution to human knowledge you may be able to imagine!" What would you wish for? We then asked the audience to think about the global knowledge work as a mechanism or algorithm; and to imagine what sort of contribution to knowledge a significant improvement to this algorithm would be. We then re-told the story about the post-war sociology, as told by Pierre Bourdieu, to show that even enormously large, orders-of-magnitude improvements are possible! Hear the beginning of our 2009 evangelizing talk at the Trinity College, Dublin, or read (a milder version) at the beginning of this article.

Knowledge Work Has a Flat Tire is a springboard story we told was the beginning of one of our two 2011 Knowledge Federation introductory talks to Stanford University, Silicon Valley and the world of innovation (see the blog post Knowledge Federation – an Enabler of Systemic Innovation, and the article linked therein). Eight Vignettes to Evangelize a Paradigm is a collection of such stories.

The incredible history of Doug continues

Bring to mind again the image of Galilei in house prison... It is most fascinating to observe how even most useful and natural ideas, when they challenge the prevailing paradigm, are ignored or resisted by even the best among us. The Google doc Completing Engelbart's Unfinished Revolution, is our recent proposal to some of the leaders of Stanford University and Google (who knew us and about us from before). Part of the story is about how Doug Engelbart's larger-than-life message, and "call to action" were outright ignored at the presentation of Doug at Google in 2007. And if you can read it between the lines, you'll in it yet another interesting story – showing the inability of the current leaders to allocate the time and attention needed for understanding the emerging paradigm; and pointing to a large opportunity for new, more courageous and more visionary leaders to take the lead.

Unraveling the mystery

... the theory that explains the data... how we've been evolving culturally ... as homo ludens, as turf animals... see it also in this way... huge paradox - homo ludens academicus...

HEY but this is really the whole point!!!

When the above stories are heard and digested, not only the story of Engelbart must seem incredible, but really the entire big thing: How can it be possible that we the people (and so clever people none the less – The Valley!) have ignored insights whose importance literally cannot be overstated? What is really going on? Perhaps there is something we need to understand about ourselves, something very basic, that we haven't seen before? It turns out – and isn't this what the large paradigm changes really are about – that the heart of the matter will be in an entirely different perception of the human condition, with entirely new issues... That is what The Paradigm Strategy poster aims to model, as one of our prototypes. Here is where the vignette are woven together into all those higher-level constructs: threads, patterns, and ultimately to a gestalt, showing what is to be done. The giants here are mostly from the humanities, linguistics, cognitive science – Bauman, Bourdieu, Chomsky, Damasio, Nietzsche... We'll say more about the substance of this conversation piece in Federation through Conversations. For now you may explore The Paradigm Strategy poster on your own.