Difference between revisions of "Main Page"

m |

m |

||

| Line 137: | Line 137: | ||

<div class="col-md-3"></div> | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

<div class="col-md-7"> | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| − | <p>To some of us in Knowledge Federation Doug has been both an inspirational figure | + | <p>To some of us in Knowledge Federation Doug has been both an inspirational figure and a revered friend.</p> |

| − | <p>We are making this website public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Engelbart's Demo – where the revolutionary technology and ideas he created were shown to public.</p> | + | <p>We are making this website public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Engelbart's Demo – where the revolutionary technology and ideas he created were first shown to public.</p> |

</div></div> | </div></div> | ||

----- | ----- | ||

Revision as of 15:16, 24 October 2018

Contents

Introducing our initiative

A historical parallel

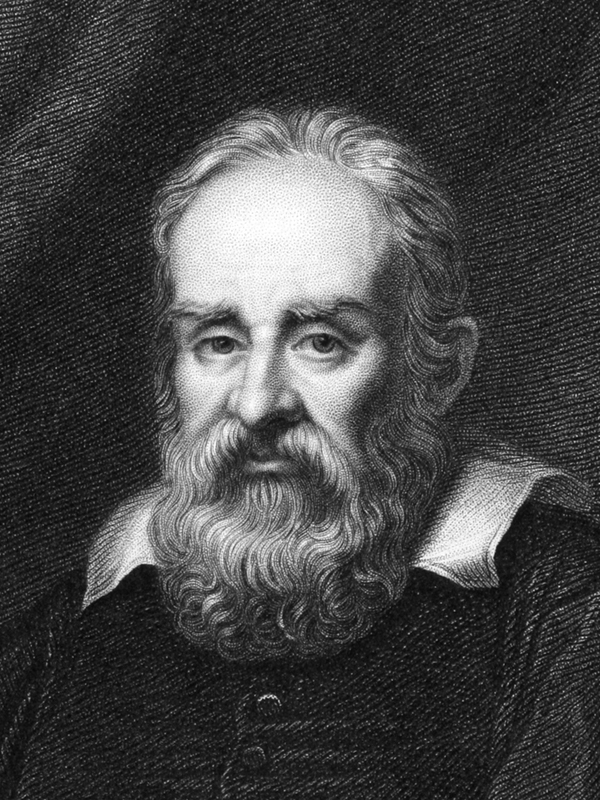

To understand the vision that motivates our initiative, think about the world at the twilight of the Middle Ages and the dawn of the Renaissance. Recall the devastating religious wars, terrifying epidemics... Bring to mind the iconic image of the scholastics discussing "how many angels can dance on a needle point". And another iconic image, of Galilei in house arrest a century after Copernicus, whispering "and yet it moves" into his beard.

Observe that the problems of the epoch were not resolved by focusing on those problems, but by a slow and steady development of an entirely new approach to knowledge. Several centuries of accelerated and sweeping evolution followed. Could a similar advent be in store for us today?

Our discovery

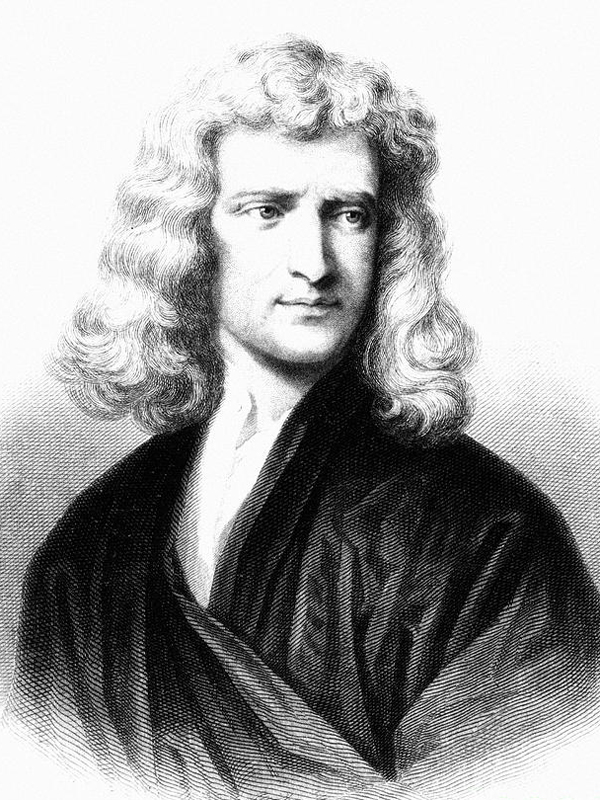

"If I have seen further," Sir Isaac Newton famously declared, "it is by standing on the shoulders of giants." The point of departure of our initiative was a discovery. We did not discover that the best ideas of our best minds were drowning in an ocean of glut. Vannevar Bush, a giant, diagnosed that nearly three quarters of a century ago. He urged the scientists to focus on that disturbing trend and find a remedy. But needless to say, this too drowned in glut.

What we did find out, when we began to develop and apply knowledge federation as a remedial practice, was that now just as in Newton's time, the insights of giants add up to a novel approach to knowledge. And that just as the case was then, the new approach to knowledge leads to new ways in which core issues are understood and handled.

Our strategy

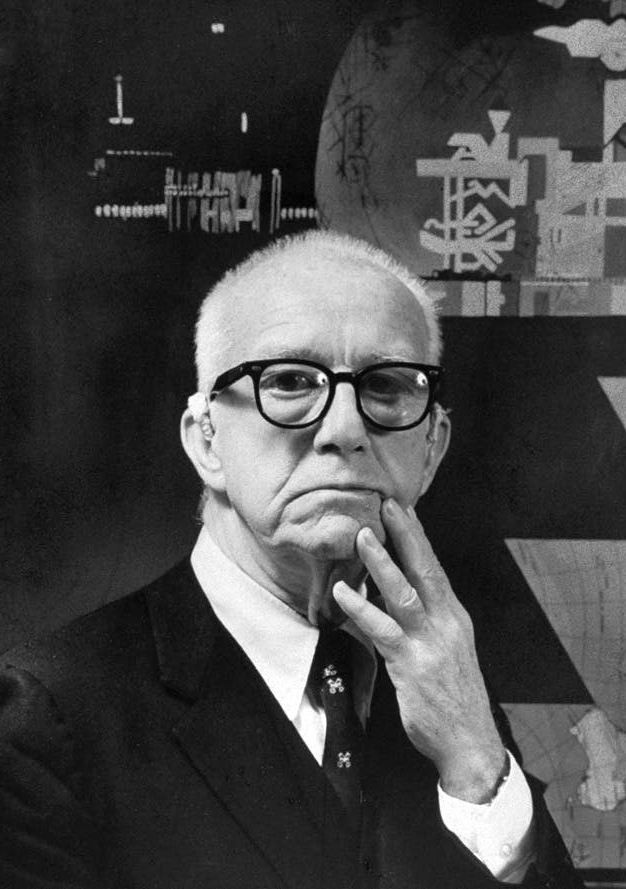

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality", observed Buckminster Fuller. "To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” So we built knowledge federation as a model (or technically a prototype) of a new way to work with knowledge (or a paradigm); and of a new institution (the transdiscipline) that is capable of developing this new new approach to knowledge as an academic and real-life praxis (informed practice).

By sharing this model we do not aim at conclusive answers. Our aim is indeed much higher – it is to open up a creative frontier where the ways in which knowledge is created and used, and more generally the ways in which our creative efforts are directed, are brought into focus and continuously recreated and improved.

Introducing knowledge federation

Connecting the dots

As our logo might suggest, knowledge federation means 'connecting the dots' – combining disparate pieces of information and other knowledge resources together, so that they may make sense, or function, in a new way. We adopted this keyword from political and institutional federation, where smaller entities are united to achieve higher visibility and impact – while preserving some suitable degree of their identity and autonomy.

Big picture science

If the word "paradigm" may not mean much to you, think of knowledge federation simply as big picture science.

"There is only one quality more important than "know how". This is "know what" by which we determine not only how to accomplish our purposes but what our purposes are to be."

This Norbert Wiener's observation is the key to understanding what practical difference a suitable big picture science might make. Science has given us a tremendously powerful "know how". We now need a similarly powerful "know what" to know how to use it beneficially and safely. We need the big picture science, the "know what", to be able to understand what specific results mean – and why they are relevant to us. The "know what" knowledge is needed to secure that the disciplinary academic results have the real-world impact they need to have.

Contemporary media informing does not give us the big picture either. The journalists alone cannot possibly synthesize the knowledge we own into a big picture.

With the information we have, we are like the people lost in a forest, who can only see the trees but not the forest. By seeing the trees, we are capable of navigating through them. And by not seeing the forest, we remain incapable of choosing a direction. Hence we choose our way in the only way that's still available – by finding a well-frequented trail and following the crowd. But a crowd of people too can be lost!

Our vision

We are not proposing to replace science and journalism, but to complement them. And also to link them with each other, and with the arts and the technological innovation and other creative fields.

We submit that it is mandatory to put in place a new socio-technical infrastructure, with its own division and organization of creative work, just as science and journalism now have. We need the praxis of producing big-picture knowledge, guiding principles, rules of thumb – to inform the core issues of our personal and social lives. What issues may benefit from such knowledge? What might the information that carries it be like? In what way may it be created? We need a new academic praxis to answer such questions. Part of our purpose is to provide sufficiently rich and solid answers to consolidate a proof of concept, to show that this indeed can and needs to be done. And to initiate the doing.

A natural approach to knowledge

What we have undertaken to put in place is what one might call the natural approach to knowledge. Think on the one side of all the knowledge we own, in academic articles and also broader. Include the heritage of the world traditions. Include the insights reached by creative people daily. Think on the other side of all the questions we need to have answered. Think of all the insights that could inform our lives, the rules of thumb that could direct our action. Imagine them occupying distinct levels of generality. The more general an insight is, the more useful it can be. You may now understand knowledge federation as whatever we the people may need to do to create, organize, synchronize, update and keep up to date the various elements of this hierarchy.

Put simply, knowledge federation is the creation and use of knowledge as we may need it – to be able to understand the increasingly complex world around us; to be able to live and act in it in an informed, sustainable or simply better way.

You may think of knowledge federation as a way to liberate science from disciplinary constraints, combine it with what we've learn about knowledge and knowledge work from journalism, art and communication design, and apply the result to illuminate any question or issue where prejudices and illusions still need to be dispelled.

Our vision is of an informed post-traditional and post-industrial society – where our understanding and handling of the core issues of our lives and times reflect the best available knowledge; where knowledge is created and integrated and applied with that goal in mind; and where information technology is developed and used accordingly.

And yet it's a paradigm

"But we cannot just create a new academic field out of nothing", we imagine might be your complaint. "Our ideas of what constitutes good knowledge have been evolving since antiquity – and now find their foremost expression in science and philosophy." Part of our purpose is to show that the state of the art in science and philosophy not only enables, but indeed requires that we – that is, those of us who are academic professionals or otherwise professionally in charge of giving good knowledge to people – develop an entirely new set of fundamental principles and practices that will orient our handling of knowledge; and our innovation and other creative work in general.

A related part of our purpose is to prime the development of this praxis – by offering knowledge federation as an initial prototype.

Reflection

Different thinking

In what ways may our thinking need be different, if we should be able to understand and develop a paradigm?We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

First of all, we need to give it the time it requires. A paradigm being a harmonious yet complex web of relationships, some amount of mental processing is obviously unavoidable if we should be able to form a coherent mental image, see that the things really do fit together a lot better when rearranged in a new way.

Systemic thinking

Another way in which our thinking needs to be different, we propose, is that it must be systemic. This very brief intuitive introduction to systemic thinking will help you pause and take a moment to reflect, at this suitable point. And it will also point to some down-to-earth social realities for you to look at in this new way – and already anticipate what all this may mean concretely.

Knowledge federation introduces itself

Knowledge federation as a language

Science taught us to think in terms of velocities and masses and experiments and natural causes. Knowledge federation too is a way to think and speak.

We'll now let knowledge federation introduce itself in its own manner of speaking.

Before we do that, this brief historical note will help you see why that manner of speaking is just a straight-forward adaptation of conventional science.

Science as a language

The rediscovery of Aristotle (whose works had been preserved by the Arabs) was a milestone in medieval history. But the scholastics used his rational method to only argue the truths of the Scriptures.

Aristotle's natural philosophy was common-sense: Objects tend to fall down; the heavier objects tend to fall faster than the lighter ones. Galilei saw a flaw in this theory and proved it wrong experimentally, by throwing stones from the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

Galilei – undoubtedly one of Newton's "giants" – also brought mathematics into this affaire: v = gt. The constant g can be measured by an experiment. We can then use the formula to predict precisely what speed v an object will have after t seconds of falling.

This approach to knowledge proved to be so superior to what existed, and so fertile, that it naturally became the standard of excellence that all knowledge was expected to emulate.

A curious-looking mathematical formula

But why use only maths?

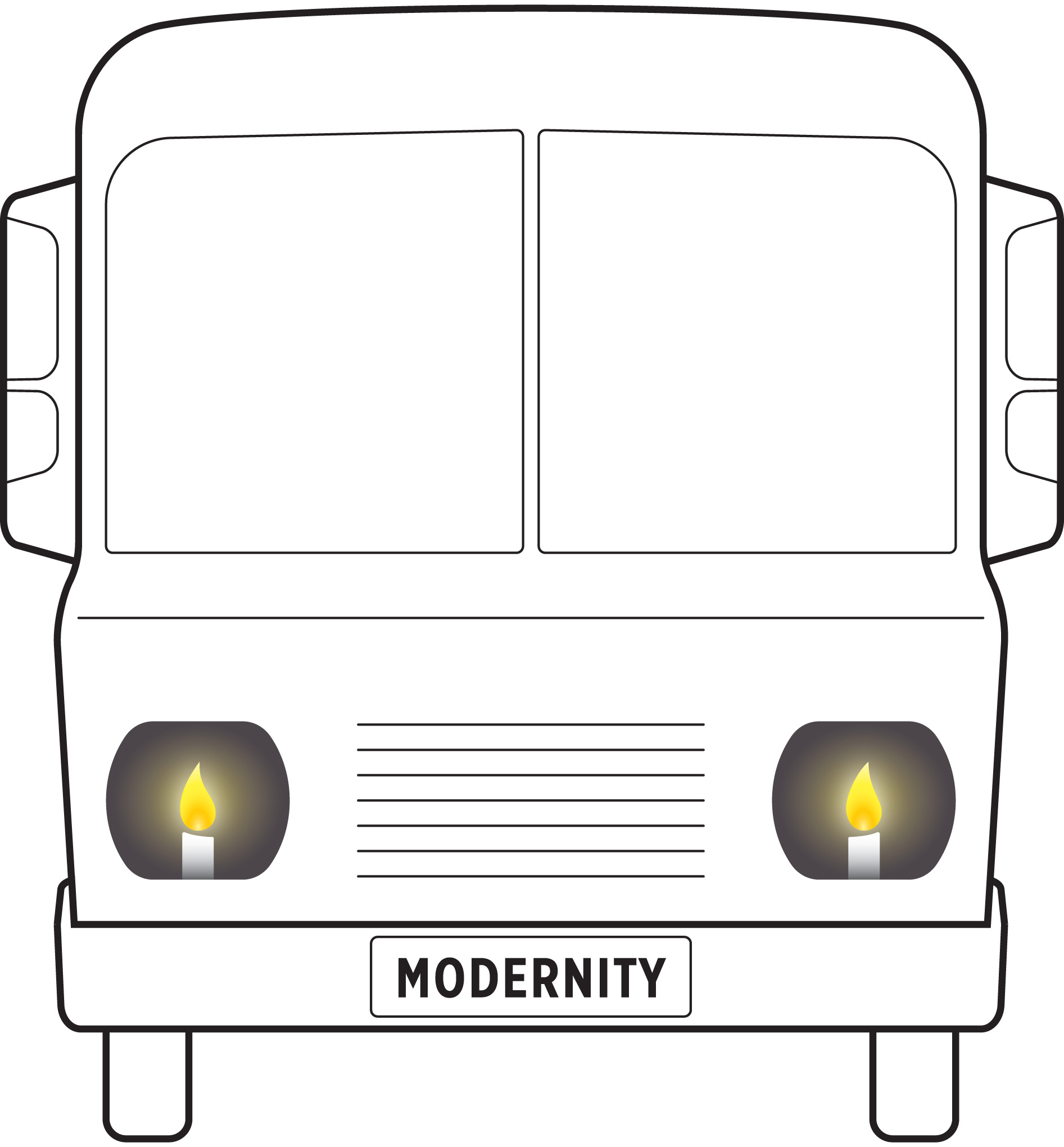

Ideograms can be understood as a straight-forward generalization of the language of mathematics. Think of the above example as a curious-looking mathematical formula. Just as Galilei's formula did, this ideogram describes a relationship (called pattern) between two things, represented by the bus and its headlights. But while mathematical formulas can express only quantitative relationships, an ideogram can represent virtually any relationship, even an emotional one.

An ideogram can also express the nature of a situation (for which we use the keyword gestalt)! Imagine us riding in a bus with candle headlights, through dark and unfamiliar terrain and at an accelerating speed. By depicting modernity as a bus with candle headlights, the Modernity ideogram points to an incongruity and a paradox. In our hither-to modernization we have forgotten to modernize something quite essential – and ended up in peril.

But there's a natural remedy!

Unraveling the paradox

A mathematical formula is just an abstract relationship, which acquires a concrete meaning – becomes "physics" – when we interpret its variables; when we say that v is the velocity of a falling object and t is the elapsed time. The formula then tells us how those entities are to be adjusted to each other.

Notice that even when interpreted in this way, the relationship remains an ideal one. "Free fall" is only an abstraction; Galilei's formula will not explain the falling of a parachutist or a feather.

In an analogous way, the Modernity ideogram expresses an abstract relationship between two entities, the bus and its headlights. It tells us how those entities are to be adjusted to one another. We can now make this abstract relationship concrete, and also useful, by assigning concrete interpretations to those two entities – just as we do in science.

We take advantage of the Modernity ideogram and define four new concepts. They will help us explain precisely what may need to be done to resolve the disquieting situation the ideogram is pointing to. They will also allow us to point precisely to four ways in which our creation and use of knowledge, our creative work in general, and societal evolution (or ride into the future) at large may need to be different.

Notice that what we are talking about is still just an abstract theory. Its relevance and accuracy will need to be confirmed by resorting to experience. That is what the remainder of this website, its four main modules, will provide.

Design epistemology

The larger issue here is epistemology – by which we mean the assumptions and values that determine what knowledge is considered worth creating and relying on.

If you consider the light of the headlights to be information or knowledge, and the headlights to represent the activities by which knowledge is created and applied, then you'll easily understand the interpretation we are pointing at. The design epistemology means considering knowledge and knowledge work as man-made things; and as essential building blocks in a much larger thing, or things, or systems. This new epistemology empowers us to develop knowledge and knowledge work and to apply them and to assess their value based on how well they serve their core roles within larger systems – such as 'showing the way'.

Notice how thoroughly this epistemology reconfigures the value matrix that orients our knowledge work today. When knowledge is considered to be pieces in a reality puzzle, then every piece might seem equally relevant. The media can then select whatever its audiences may be interested in. But when knowledge is conceived of as the light that needs to show us the next curve on the road, then the priorities are entirely different. Relevance, and the nature and the quality of information that provides the right insight and guidance, become core issues.

Furthermore those core issues become research issues. The research that tends to be most valued and considered academically fundamental or "basic" is the one whose aim is to discover the details of the puzzle of nature. In the order of things pointed to by the design epistemology, it is the research whose goal is to construct the core elements of an entirely different puzzle – of the socio-technical system or systems by which knowledge is created and disseminated – that becomes fundamental or basic. The most honored product of conventional science is an academic article in a reputed publication. In this new order of things the honor belongs just as much to the most impactful creative act, of any kind – that may bring the process of dissolving the core anomaly a step further.

In Federation through Images we will explain how exactly this idea can be extended into a complete paradigm. To see that the epistemology is at the core of every paradigm, and of the general paradigm we call science in particular, notice that Galilei was not tried for claiming that the Earth was moving. That was just a technical detail. It was his epistemology that got him into trouble – his belief that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. Galilei was required to "abjure, curse and detest" those opinions (Wikipedia).

Knowledge federation

You may now understand knowledge federation as simply suitable 'headlights', as the quest for those 'headlights', and as the 'factory' (transdiscipline) capable of creating them. You may also understand knowledge federation as the knowledge and knowledge work that follow by consistent application of the design epistemology.

The Modernity ideogram also bears a subtler message. What the bus with candle headlights is lacking above all are the high-beam headlights – which can illuminate a long-enough stretch of the road to provide for safe driving. You may now easily see how this points to the need for a "big picture science". You may also see the Modernity ideogram as the first example of a suitable big-picture result – which reveals the nature a situation and shows what needs to be done.

No sequence of improvements of the candle will produce the lightbulb. The resolution of our quest is in the exact sense of the word a paradigm – a fundamentally and thoroughly new way to conceive of knowledge and to organize its handling. To create the lightbulb, we need to know that this is possible. And we also need a model. You will now easily understand what's being told here as a description of that model. Why waste time trying to improve 'the candle' – when it's really 'the lightbulb' we should be talking about and creating?

Systemic innovation

If you consider the movement of the bus to be the result of our creative efforts or of "innovation", then systemic innovation is what resolves the paradox that the Modernity ideogram is pointing to. You may understand systemic innovation as informed innovation, as the way we'll innovate when a strong-enough light's been turned on.

We practice systemic innovation when our primary goal is to make the whole thing functional or vital or whole. Here "the whole thing" may of course be a whole hierarchy of things, in which what we are doing or creating has a role.

There are two complementary ways to say what systemic innovation is. One is to (focus on the bus and) say that systemic innovation is innovation on the scale of the large and basic socio-technical systems, such as education, public informing, and knowledge work at large. The other one is to (focus on the headlights and) say that systemic innovation is innovation whose primary aim and responsibility is the good condition or functioning or wholeness of the system or systems in which what we are creating has a role. But of course those two definitions are just two ways of saying the same thing.

Here too there's a subtle message. You'll easily understand the reason, why a dramatic improvement in the way we use our capacity to create or innovate is possible, if you just compare the principle the Modernity ideogram is pointing at with the way innovation is directed today. The dollar value of the headlights is course a factor to be considered; but it's insignificant compared to the value of the whole bus (which in reality may be our civilization and all of us in it; or all our technology taken together; or the results of our daily work, which move the 'bus' forward; or whatever else may be organizing our efforts and driving us toward a future). It is this difference in value – between the dollar value of the headlights and the real value of this incomparably larger entity and of all of us in it – that you may bear in mind as systemic innovation's value proposition. The dramatic message of our image is that systemic innovation is what can make the difference between "the whole thing" turning into a mass suicide machine – and a well-functioning vehicle, capable of taking us anywhere we may reasonably want to be.

To see that the change this is pointing to reaches well beyond industrial innovation, to see why we indeed propose systemic innovation as the signature theme of an impending Renaissance-like change, notice that the dollar value is just one of our characteristic oversimplifications, which has enabled us to reduce a complex issue (value) in a complex reality to a single parameter – and then apply rational or 'scientific' thinking to optimize our behavior accordingly.

Guided evolution of society

If you'll consider the movement of the bus to be our society's travel into the future, or in a word its evolution, then guided evolution of society is what resolves the paradox. Our ride into the future, posits the Modernity ideogram, must be illuminated by suitable information. We must both create and use information accordingly.

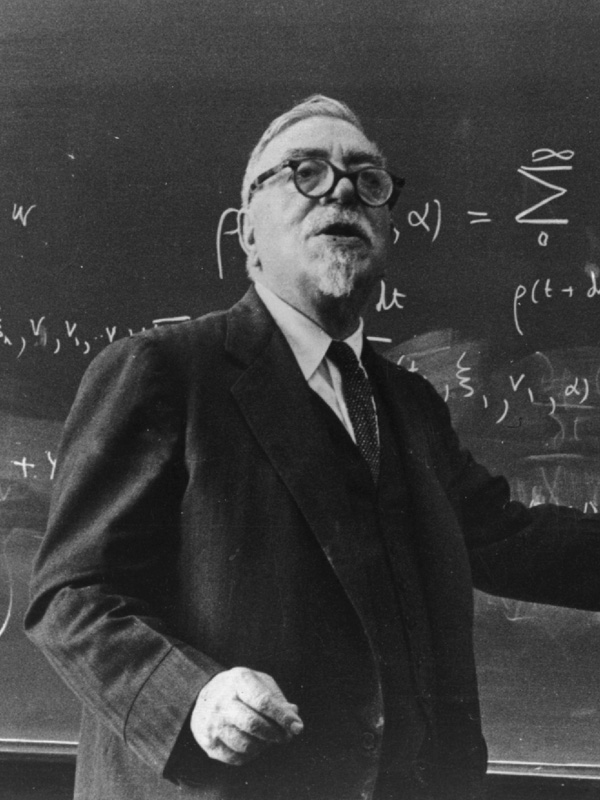

We took this keyword from Bela H. Banathy, who considered the guided evolution of society to be the second great revolution in our civilization's history – the first one being the agricultural revolution. While in this first revolution we learned to cultivate our bio-physical environment, in the next one we'll learn to cultivate our socio-cultural environment. Here is how Banathy formulated this vision:

We are the first generation of our species that has the privilege, the opportunity, and the burden of responsibility to engage in the process of our own evolution. We are indeed chosen people. We now have the knowledge available to us and we have the power of human and social potential that is required to initiate a new and historical social function: conscious evolution. But we can fulfill this function only if we develop evolutionary competence by evolutionary learning and acquire the will and determination to engage in conscious evolution. These are core requirements, because what evolution did for us up to now we have to learn to do for ourselves by guiding our own evolution.

Completing Engelbart's unfinished revolution

A new iconic image

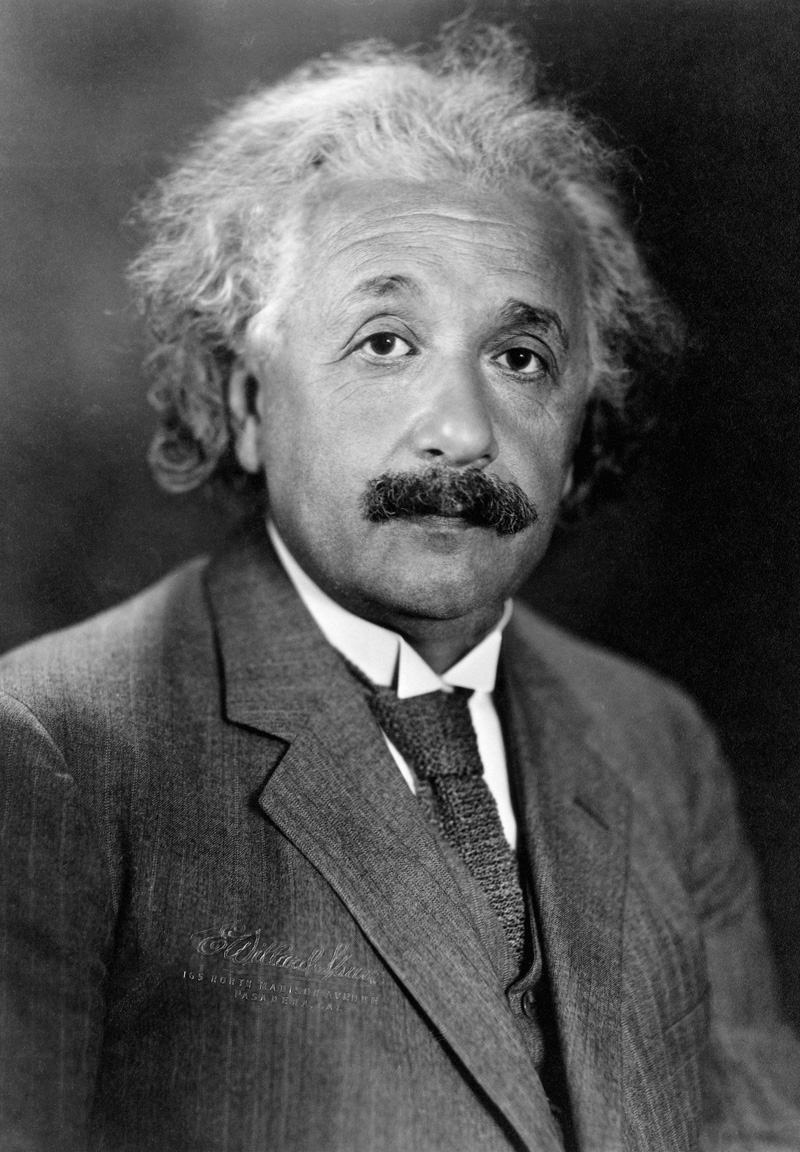

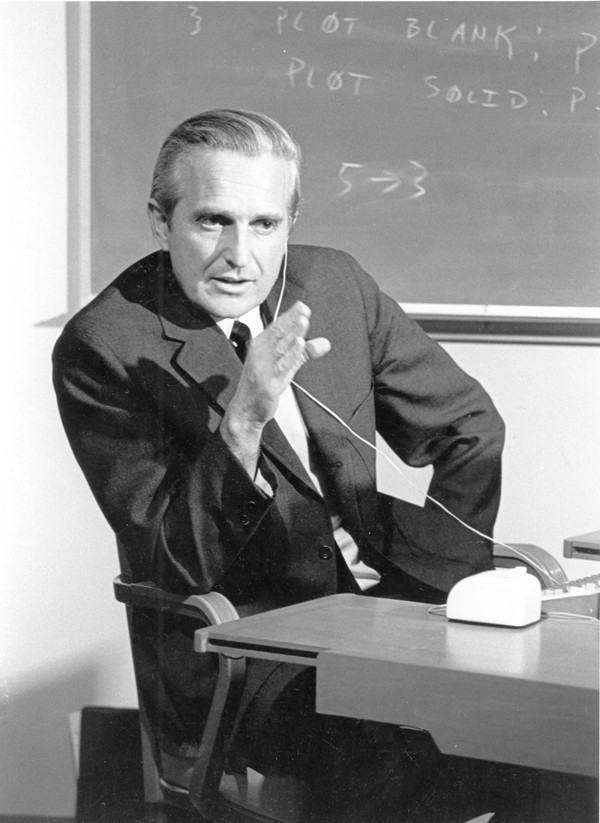

Of the many iconic stories you will find of these pages, there is one that we feel compelled to highlight on this front page – the story of Douglas Engelbart and of his "unfinished revolution". This story is about a man who created some of the most significant parts of the knowledge media technology we have today. And who did that by pursuing a much larger vision, whose essence has remained ignored – and to whose completion we have humbly endeavored to contribute.

As we shall see in Federation through Stories, these two sentences were intended to frame Engelbart's message to the world. We shall see that the required new thinking is precisely systemic thinking or systemic innovation, we have been pointing to.Digital technology could help make this a better world. But we've also got to change our way of thinking.

Engelbart, as we shall show, envisioned and created knowledge federation and systemic innovation – although he never used these keywords.

To some of us in Knowledge Federation Doug has been both an inspirational figure and a revered friend.

We are making this website public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Engelbart's Demo – where the revolutionary technology and ideas he created were first shown to public.

Summary

How we plead our case

We use knowledge federation to explain, showcase and propose knowledge federation.

Each of the four main modules of this website will use a specific set of techniques – to focus on a specific side of our issue.

Our immediate goal is to make a case for a new paradigm in knowledge work – to be added to the academic repertoire of fields and activities, and integrated in conventional institutional repertoire of practices. And to initiate an structured public dialog – which will both enable our proposal to evolve further, by engaging everyone's collective intelligence. And which will also build the new communication infrastructure, as a public sphere capable of assimilating the insights of giants, building on them through everyone's engagement and contribution, and producing the kind of guiding insights that are now urgently needed.

Federation through Images

The focus is, roughly, on design epistemology and its consequences.

We show how big picture scientific method can be developed RIGOROUSLY, based on state of the art insights in science and philosophy.

We use ideograms to create a cartoon-like introduction of the philosophical underpinnings of a refreshingly novel approach to knowledge.

Federation through Stories

We use vignettes – short, lively, catchy, sticky... real-life people and situation stories – to explain and empower some of the core ideas of daring thinkers. A vignette liberates an insight from the language of a discipline and enables a non-expert to 'step into the shoes' of a leading thinker, 'look through his eye glasses'. By combining vignettes into threads, and threads into higher units of meaning, we take this process of federation all the way to the kind of direction-setting principles we've just been talking about.

The four vignettes will roughly correspond to the four keywords we introduced above, respectively.

Each will, we submit respectfully, be sufficient on its own to justify our proposal.

Federation through Applications

We cover the knowledge federation / systemic innovation creative frontiers by showing examples. What might journalism be like, which would be capable of draw insights from relevant areas of knowledge, and combining them to provide suitable orientation and guidelines to the people in the complex world? In what way might we distill the core ideas from a technical scientific result and make them accessible wider audiences? In what way may education need to be different to enable (and not hinder) social-systemic change? Those and many other questions are answered by showing concrete practical applications – already embedded in practice.

The "applications" here are prototypes – which are the kind of results that are suitable to ...

Federation through Conversations

Here we both sharpen the focus – by choosing three themes that will ignite the change. And we initiate the public dialogs.