STORIES

Contents

Federation through Stories

Modern physics had a gift for humanity

Unraveling the rigid frame

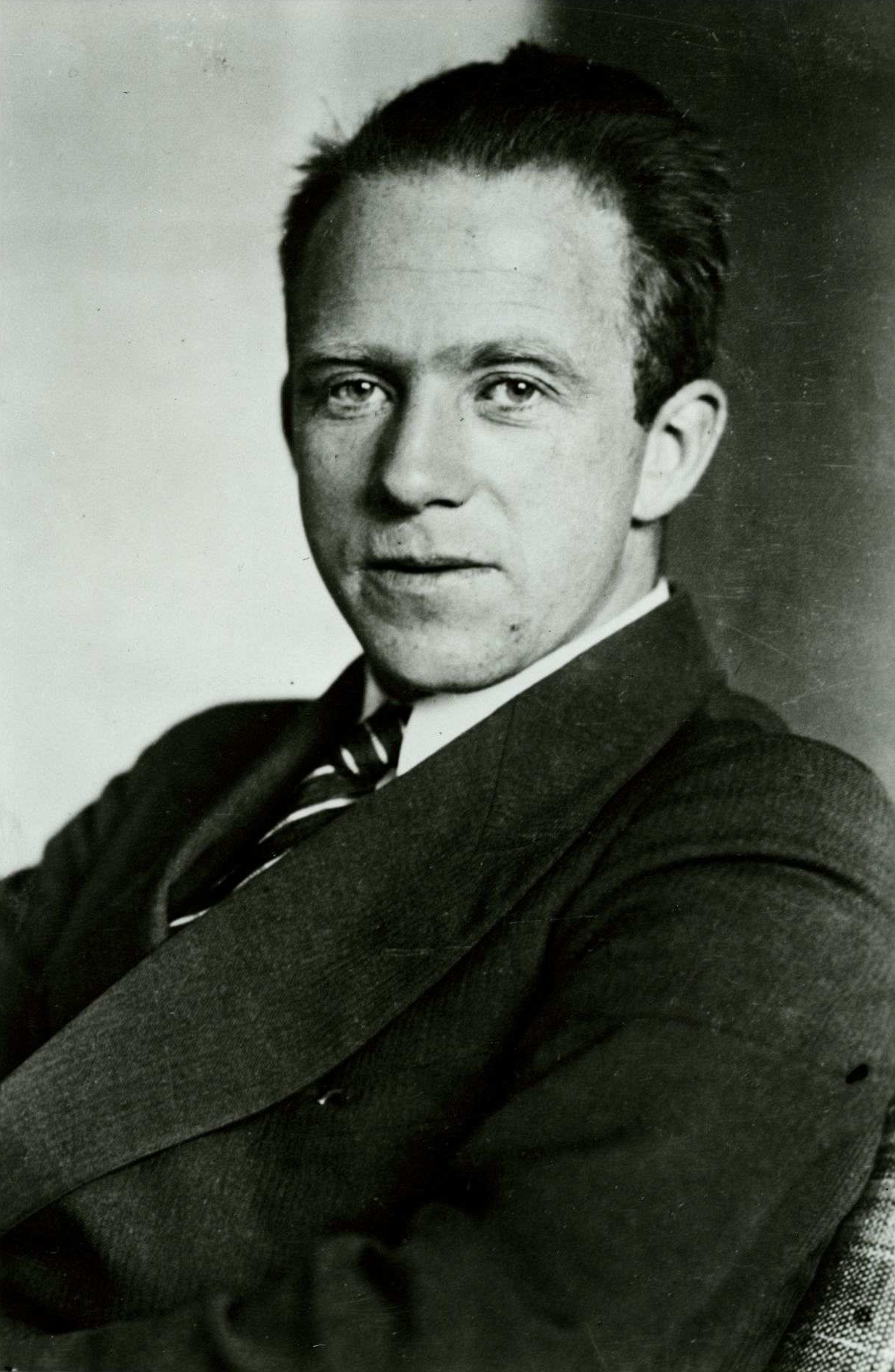

(T)he nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people.

Werner Heisenberg got his Nobel Prize in 1932, "for the creation of quantum mechanics" which he did while still in his twenties. As a mature scientist he realized, however, that modern physics had a gift for humanity that was well beyond physics or even science at large, which had not been recognized. To correct that, in 1958 he published "Physics and Philosophy" (subtitled "the revolution in modern science"), from which the above excerpt was taken.

In this manuscript, Heisenberg explained how science rose to prominence based on its fascinating successes in deciphering the secrets of nature. And how, as a side effect, the specialized way of looking that led to those successes in the specialized domains of science became dominant also elsewhere – which was damaging to those finer sides of our social and cultural existence where this "rigid frame" could no longer be reasonably applied.

Heisenberg then explained how modern physics disproved this "narrow frame"; and concluded that

one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century.

Please pause for a moment to reflect about what this really means. A modern physicist is telling us that perhaps "the most important change brought about" by modern physics was the dissolution of the rigid frame.

The rigid frame – and its ethical and cultural consequences – are, however, now at least as strong in everyday life as they were in Heisenberg's time! Cultural processes were set into motion which are not so easily reversed.

If we now (in the spirit of systemic innovation, and the emerging paradigm) consider that the social role of the university (as institution) is to provide good knowledge and viable standards for good knowledge – then we see that just this Heisenberg's insight alone gives us an obligation to correct the error he was pointing to – which we've failed to attend to for sixty years.

The incredible history of Doug

An epiphany

In December of 1950 Douglas Engelbart was a young engineer newly graduated from university, just engaged and freshly employed. He was looking at his career as a straight path to retirement. And he did not like what he saw.

Life should be more than that! So he made a decision – to direct his career so as to maximize its benefits to the mankind.

Facing now an interesting optimization problem, this idealistic young engineer spent three months thinking intensely how exactly to direct his efforts. Then he had an epiphany. The computer had just been invented. And the humanity had all those problems that were growing in complexity and urgency, which it didn't know how to solve. What if...

To begin to pursue his vision, Engelbart quit his job and enrolled at the doctoral program in computer science at U.C. Berkeley.

How Silicon Valley failed to understand its giant in residence

It took awhile for the people in Silicon Valley to realize that the core technologies were not developed by Steve Jobs and Bill Gates; nor at the XEROX Palo Alto Research Center where they took them from – but by Douglas Engelbart and his SRI-based research team. On December 9, 1998 a large conference was organized at Stanford University to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Engelbart's Demo, where the networked interactive digital media technology – the kind of thing that is in common use today – was first shown to the public. Engelbart received the highest honors including the Presidental award and the Turing prize (a computer science equivalent to Nobel Prize). Allen Kay (another Silicon Valley personal computing pioneer) remarked "What will the Silicon Valley do when they run out of Doug's ideas?".

And yet it was clear to Doug – and he also made it clear to others – that he felt celebrated for wrong reasons. The crux of his vision remained unfulfilled, and even ignored. Doug was notorious for telling people "You just don't get it!"

On July 2, 2013 Doug passed away, celebrated and honored – yet feeling he had failed.

The Silicon Valley failed to understand its giant in residence – even after having recognized him as that!

The 21 century printing press

What was it that the Silicon Valley developers, business leaders and academics "just didn't get"?

The printing press is a fitting metaphor for answering this question, in the context of our big picture story, because the printing press was to a large degree the technical invention that led to the Enlightenment, by making knowledge widely accessible. If we would now ask what technology might play a similar role in the next Enlightenment-like change, you would most probably answer "the Web or (if you are technical) "the network-interconnected interactive digital media". And your answer would be right.

But there's a catch!

While there can be no doubt that the printing press led to a revolution in knowledge work, this revolution was only a revolution in quantity. The printing press only made what the scribes were doing more efficient! To communicate, people still needed to write and publish books, and hope that the people who needed what's written in them would find them on a shelf.

The network-interconnected interactive digital media, however, is a disruptive technology of a completely new kind; it is not a broadcasting device, but in a truest sense a "nervous system" connecting people together.

There are two very different ways in which this technology can be developed and put to use.

One of them is the habitual way – to use it as we used the printing press, to just increase the efficiency of what the people were already doing, help them print and publish faster all those articles and books and letters and...? (In the language of our central metaphor, this would mean using the new electrical technology to re-implement the candle.)

To see the problem this way of using the new technology most naturally leads to, imagine that your own nervous system were used in this way; that all your sensory cells were using your nervous system to just broadcast data to your brain. Your sanity would surely suffer. Well that's what has happened with (to use one of Doug's favorite keywords) our collective intelligence.

Neil Postman would observe – in 1990, just before the Web:

The tie between information and action has been severed. ...It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it.

Engelbart's legacy

Digital technology could help make this a better world. But we've also got to change our way of thinking.

These two sentences were intended to frame Engelbart's message to the world – that was to be delivered at Google in 2007. </p>

If there is sill doubt that it was systemic thinking Doug had in mind, consider the following excerpt (from an interview Doug gave as a part of a Stanford University research project):

I remember reading about the people that would go in and lick malaria in an area, and then the population would grow so fast and the people didn't take care of the ecology, and so pretty soon they were starving again, because they not only couldn't feed themselves, but the soil was eroding so fast that the productivity of the land was going to go down. Sol it's a case that the side effects didn't produce what you thought the direct benefits would. I began to realize it's a very complex world. I began to realize it's a very complex world. (...) Someplace along there, I just had this flash that, hey, what that really says is that the complexity of a lot of the problems and the means for solving thyem are just getting to be too much. So the urgency goes up. So then I put it together that the product of these two factors, complexity and urgency, are the measure for human organizations or institutions. The complexity/urgency factor had transcended what humans can cope with. It suddenly flashed tthat if you could do something to improve human capability to deal with that, then you'd realy contribute something basic. That just resonated. Then it unfolded rapidly. I think it was just within an hour that I had the image of sitting at a big CRT screen with all kinds of symbols, new and different symbols, not restricted to our old ones. The computer could be manipulating, and you could be operating all kinds of things to drive the computer. The engineering was easy to do; you could harness any kind of a lever or knob, or buttons, or switches, you wanted to, and the computer could sense them, and do something with it.

To see the crux of Engelbart's intended contribution to humanity, reflect on the difference a functioning nervous system could make with respect to humanity's ability to deal with complexity and urgency. To see why "different thinking" alias systemic innovation is necessary to get us there, imagine yourself walking toward a wall. Imagine that your eyes see that, but they are trying to tell it to your brain by writing academic articles in some specialized field of knowledge.

What the humanity's new nervous system required was, of course, a completely new division, specialization and coordination of knowledge work – that would turn the physical nervous system into a well-functioning one. And this is the context in which Engelbart's various less known technical contributions need to be understood. All of them – the open hyperdocument system, the networked improvement community, the dynamic knowledge repository and numerous others – were intended to be, and can only be understood, as building blocks in a completely new approach to knowledge.

While Engelbart was celebrated as a genius technology developer, his contribution will only be properly recognized when we consider it as a revolutionary contribution to human knowledge – or in other words as in the proper sense of the word academic.

But alas – Engelbar was only making a pivotal contribution to humanity's handling of knowledge; and to humanity's future. Having thus failed to be part of any of the recognized academic disciplines, his contribution remained unrecognized.

Reflection

The way ahead

We are now at a point where the view of our present evolutionary moment has become very clear. The nervous system metaphor can help! Read our brief vision statement and then reflect about what we must do to respond to the pressing need of this moment – to learn to coordinate the action of our society's organs and organ systems, and in that way take advantage of our society's 'nervous system' we've just acquired.

The future of the university

Subtitle

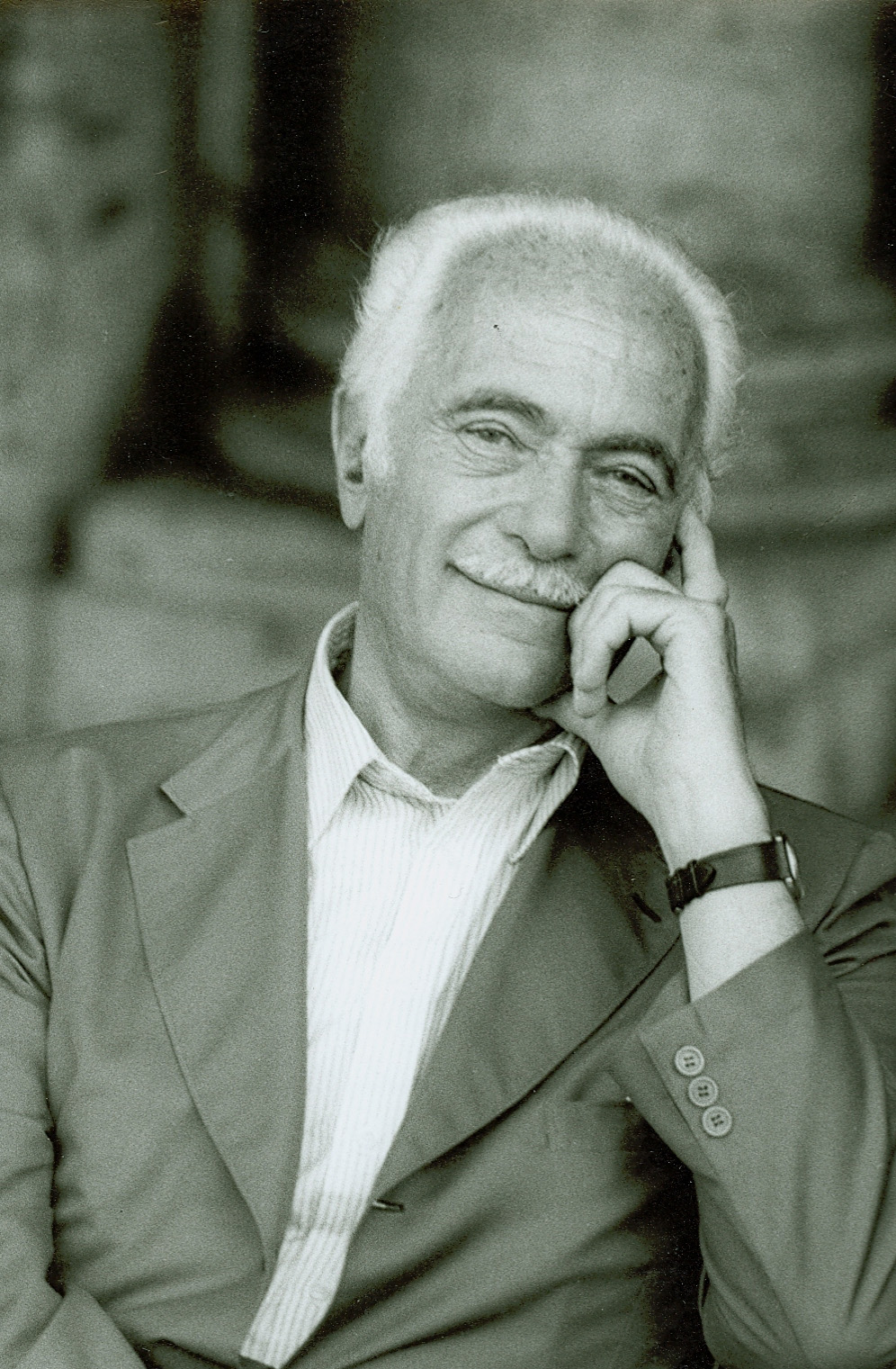

Fifty years ago Erich Jantsch made a proposal for the university of the future, and made an appeal that the university take the new leadership role which, as he saw it, was due.

[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewal.

Suppose the university did that. Suppose that we opened up the university to take such a leadership role. What new ways of working, results, effects... could be achieved? What might this new creative frontier look like, what might it consist of, how may it be organized?

The technique demonstrated here is the prototypes – which are the characteristic products of systemic innovation. Here's a related question to consider: If we should aim at systemic impact, if our key goal is to re-create systems including our own – then the traditional academic articles and book cannot be our only or even our main product. But what else should we do? And how?

Planning as feedback, systemic innovation as control

With a doctorate in physics, it was not difficult to Jantsch to put two and two together and see what needed to be done. If our civilization is on a disastrous course, and if it lacks suitable "headlights and braking and steering controls) or (to use a cybernetician's more scientific tone) "feedback and control" – then there's a single capability that we as society are lacking, which can correct this problem – the capability to look into the future, and steer the way by correcting our systems.

So right after The Club of Rome's first meeting, Jantsch gathered a group of creative leaders and researchers, mostly from the systems community, in Bellagio, Italy, to put together necessary insights and methods. The result was so basic that Jantsch called it "rational creative action". The message is obvious and central to our interest: Certainly there are many ways in which we can be creative. But if our creative action is to be rational – then these essential ingredients must be present.

Rational creative action begins with forecasting, which explores different future scenario; it ends with an action selected to enhance the likelihood of the desired scenario or scenarios. So what they called "planning" (notice that this had nothing to do with the kind of planning that was at the time used in the Soviet Union) was envisioned as the new and enhanced feedback that our society lacked in order to have control over its future:

[T]he pursuance of orthodox planning is quite insufficient, in that it seldom does more than touch a system through changes of the variables. Planning must be concerned with the structural design of the system itself and involved in the formation of policy.”

Policies, which are the objective of planning (as the authors of the Bellagio Declaration envisioned it) specify both the institutional changes and the norms and value changes that might be necessary to make our goal-oriented action in a true sense rational and creative (Jantsch, 1970):

Policies are the first expressions and guiding images of normative thinking and action. In other words, they are the spiritual agents of change—change not only in the ways and means by which bureaucracies and technocracies operate, but change in the very institutions and norms which form their homes and castles.”

The emerging role of the university

The next question in Jantsch's stream of thought and action was roughly this: If systemic innovation is a necessary new capability that our systems and our civilization at large now require, then who – that is, what institution – may be the most natural and best qualified to foster this capability? Jantsch concluded that the university (institution) will have to be the answer. And that to be able to fulfill this role, the university itself will need to update its own system.

[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewal. It may have to become a political institution, interacting with government and industry in the planning and designing of society’s systems, and controlling the outcomes of the introduction of technology into those systems. This new leadership role of the university should provide an integrated approach to world systems, particularly the ‘joint systems’ of society and technology.”In 1969 Jantsch spent a semester at the MIT, writing a 150-page report about the future of the university, from which the above excerpt was taken, and lobbying with the faculty and the administration to begin to develop this new way of thinking and working in academic practice.

Evolution is the key

In the 1970s Jantsch lived in Berkeley, wrote prolifically, and taught occasional seminars at the U.C. Berkeley. This period of his life and work was marked by a new insight, which was triggered by his experiences with working on global / systemic change, and some profound scientific insights brought to him, initially, by Ilya Prigogine, the Nobel laureate scientist who visited Berkeley in 1972. Put very briefly, this involves two closely related insights:

- we cannot – that is, nobody can – recreate the large systems including the largest, our civilization, in any way directly; where we can make a difference – and hence where we must focus on – is their evolution;

- the living and evolving systems are governed by an entirely different dynamic than physical systems – which needs to be understood</il>

Jantsch was especially interested in understanding the relationship between our – that is, people's values and ways of being, and our evolution. He saw us as entering the "evolutionary paradigm". Bela Banathy cited him extensively in "Guided Evolution of Society". The title of Jantsch's 1975 book "Design for Evolution" points unequivocally in the same direction as our four core keywords. The keyword systemic innovation we adopted from him directly.

The incredible part

Norbert Wiener was of course not alone in observing that a meta-discipline was needed, that would (1) provide a common language and body of knowledge for communication among and beyond the sciences and (2) provide us an understanding of systems, so that we may secure that they the core socio-technical systems we are creating are suitably structured, and thereby also "sustainable". Von Bertalanffy reached similar conclusions from the venture point of mathematical biology; and so did a number of others, in their own way. In 1954 Bertalanffy was joined by biologist Ralph Gerard, economist Kenneth Boulding and mathematician Anatol Rapoport at the Stanford Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences – and they created an organization that later included (as a federation) most of the others including cybernetics, and became the International Society for the Systems Sciences. Realizing the importance of this new frontier, many brave young women and men joined the systems movement, and the body of research grew immensely.

The research in the part of games theory that Wiener found especially interesting also subsequently exploded. During the 1950s more than a thousand research articles were published on the so-called "prisoner's dilemma". The message from this research that will be for our story can be found in the opening of the corresponding Wikipedia page: It is that perfectly rational competition, where everyone maximizes the personal gain, can lead to a condition where everyone is worth off than what would be reached through cooperation.

Erich Jantsch spent the last decade of his life living in Berkeley, teaching sporadic seminars at U.C. Berkeley and writing prolifically. Ironically, the man who with such passion and insight wrote about how the university would need to change to help us master our future, and lobbied for such change – never found a home and sustenance for his work at the university.

In 1980 Jantsch published two books with a wealth of insights on "evolutionary paradigm" – whose purpose was to inform the evolutionary path of our society; he passed away after a short illness, only 51 years old. An obituarist commented that his unstable income and inadequate nutrition might have been a factor. In his will Jantsch asked that his ashes be tossed into the ocean, "the cradle of evolution".

In that same year Ronald Reagan became the 40th U.S. president on the agenda that the market, or the free competition, is the only thing we can rely on. That same "simple-minded theory", as Norbert Wiener called it, marks our political life still today. It is also what directs our technological innovation and creative work in general, and hence also our travel into the future.

How to change course

Just another hero

The human race is hurtling toward a disaster. It is absolutely necessary to find a way to change course.Aurelio Peccei – the co-founder, firs president and the motor power behind The Club of Rome – wrote this in 1980, in One Hundred Pages for the Future, based on this global think tank's first decade of research.

Peccei was an unordinary man. In 1944, as a member of Italian Resistance, he was captured by the Gestapo and tortured for six months without revealing his contacts. Here is how he commented his imprisonment only 30 days upon being released:

My 11 months of captivity were one of the most enriching periods of my life, and I regard myself truly fortunate that it all happened. Being strong as a bull, I resisted very rough treatment for many days. The most vivid lesson in dignity I ever learned was that given in such extreme strains by the humblest and simplest among us who had no friends outside the prison gates to help them, nothing to rely on but their own convictions and humanity. I began to be convinced that lying latent in man is a great force for good, which awaits liberation. I had a confirmation that one can remain a free man in jail; that people can be chained but that ideas cannot.

Peccei was also an unordinarily able business leader. While serving as the director of Fiat's operations in Latin America (and securing that the cars were there not only sold but also produced) Peccei established Italconsult, a consulting and financing agency to help the developing countries catch up with the rest. When the Italian technology giant Olivetti was in trouble, Peccei was brought in as the president, and he managed to turn its fortunes around. And yet the question that most occupied Peccei was a much larger one – the condition of our civilization as a whole; and what we may need to do to take charge of this condition.

In 1977, in "The Human Quality", Peccei formulated his answer as follows:

Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world.

On the morning of the last day of his life (March 14, 1984), while dictating "The Club of Rome: Agenda for the End of the Century" to his secretary from a hospital, Peccei identified "human development" as "the most important goal".

Peccei's and Club of Rome's insights and proposals (to focus not on problems but on the condition or the "problematique" as a whole, and to handle it through systemic and evolutionary strategies and agendas) have not been ignored only by "climate deniers", but also by activists and believers.

Reflections

Putting it all together

TBA