Difference between revisions of "N-keywords"

m |

m |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

<p>"In the beginning was logos and logos was with God and the logos was God." I use <em><b>logos</b></em> as <em><b>keyword</b></em> to point to this reconstruction because it helps us comprehend what exactly went wrong and why. To the philosophers of antiquity, "logos" was the principle according to which God structured the world; which <em>enables</em> us humans to comprehend the world and dance with it harmoniously. How and why this is at all possible—here the opinions differed; and gave rise to a wealth of stream of thought and cultural directions. But "logos" did rather poorly from then on; it did not translate well into Latin; and during the Middle Ages it was believed that <em><b>logos</b></em> was revealed to us humans through God's own son; and so was all further quest of <em><b>logos</b></em> forgotten or even forbidden.</p> | <p>"In the beginning was logos and logos was with God and the logos was God." I use <em><b>logos</b></em> as <em><b>keyword</b></em> to point to this reconstruction because it helps us comprehend what exactly went wrong and why. To the philosophers of antiquity, "logos" was the principle according to which God structured the world; which <em>enables</em> us humans to comprehend the world and dance with it harmoniously. How and why this is at all possible—here the opinions differed; and gave rise to a wealth of stream of thought and cultural directions. But "logos" did rather poorly from then on; it did not translate well into Latin; and during the Middle Ages it was believed that <em><b>logos</b></em> was revealed to us humans through God's own son; and so was all further quest of <em><b>logos</b></em> forgotten or even forbidden.</p> | ||

<p>Descartes and his colleagues revived it—but conceived it as the quest for "objective" and unchanging truth; which is, they took this for granted, revealed to the mind as the <em>sensation</em> of absolute certainty. You'll now easily comprehend how from that point on <em>everything</em> went wrong: Instead of conscientiously looking at things from all sides in order to <em><b>see them whole</b></em>—we ended up getting stuck with <em>whatever</em> way of looking at things there was that gave the mind that comforting sensation; and we <em>ignored</em> whatever might threaten it!</p> | <p>Descartes and his colleagues revived it—but conceived it as the quest for "objective" and unchanging truth; which is, they took this for granted, revealed to the mind as the <em>sensation</em> of absolute certainty. You'll now easily comprehend how from that point on <em>everything</em> went wrong: Instead of conscientiously looking at things from all sides in order to <em><b>see them whole</b></em>—we ended up getting stuck with <em>whatever</em> way of looking at things there was that gave the mind that comforting sensation; and we <em>ignored</em> whatever might threaten it!</p> | ||

| − | <h3>Seduced by reductionistic comprehension—we failed to even <em>notice<em> when <b>knowledge</b></em> became impossible.</h3> | + | <h3>Seduced by reductionistic comprehension—we failed to even <em>notice</em> when <em><b>knowledge</b></em> became impossible.</h3> |

<p>In the <em>Liberation</em> book this is made transparent already in Chapter Two; where I tell the <em><b>thread</b></em> (short sequence of <em><b>vignettes</b></em>) where Nietzsche first portrays us modern humans (at the turn of the <em>twentieth</em> century!) as (already!) overwhelmed by "the abundance of disparate impressions" and "the tempo of <nowiki>[their]</nowiki> influx"; so that we "instinctively resists taking in anything, taking anything deeply"; and "unlearn spontaneous action <nowiki>[and]</nowiki> merely react to stimuli from outside". How do we cope with the overabundance of data (made to stimulate and not help us comprehend) on one side, and the staggering complexity of our world on the other, I asked; and let Anthony Giddens give an answer: “The threat of personal meaninglessness is ordinarily held at bay because routinised activities, in combination with basic trust, sustain ontological security. Potentially disturbing existential questions are defused by the controlled nature of day-to-day activities within internally referential systems." Are you beginning to see how <em><b>materialism<em><b>—our modernity's present <em><b>paradigm</b></em>—naturally emerged from this foundation? In the book I summed this up by adapting (Johan Huizinga's) <em><b>homo ludens</b></em> as <em><b>keyword</b></em>; and calling it a 'cultural species, which (unlike the cultural <em><b>homo sapiens</b></em> who seeks <em><b> knowledge</b></em> to choose directions) simply learns 'the rules of the game' of one's profession and other society's <em><b>systems</b></em>; and performs in them competitively, aiming to further (what he perceives as) his own interests.</p> | <p>In the <em>Liberation</em> book this is made transparent already in Chapter Two; where I tell the <em><b>thread</b></em> (short sequence of <em><b>vignettes</b></em>) where Nietzsche first portrays us modern humans (at the turn of the <em>twentieth</em> century!) as (already!) overwhelmed by "the abundance of disparate impressions" and "the tempo of <nowiki>[their]</nowiki> influx"; so that we "instinctively resists taking in anything, taking anything deeply"; and "unlearn spontaneous action <nowiki>[and]</nowiki> merely react to stimuli from outside". How do we cope with the overabundance of data (made to stimulate and not help us comprehend) on one side, and the staggering complexity of our world on the other, I asked; and let Anthony Giddens give an answer: “The threat of personal meaninglessness is ordinarily held at bay because routinised activities, in combination with basic trust, sustain ontological security. Potentially disturbing existential questions are defused by the controlled nature of day-to-day activities within internally referential systems." Are you beginning to see how <em><b>materialism<em><b>—our modernity's present <em><b>paradigm</b></em>—naturally emerged from this foundation? In the book I summed this up by adapting (Johan Huizinga's) <em><b>homo ludens</b></em> as <em><b>keyword</b></em>; and calling it a 'cultural species, which (unlike the cultural <em><b>homo sapiens</b></em> who seeks <em><b> knowledge</b></em> to choose directions) simply learns 'the rules of the game' of one's profession and other society's <em><b>systems</b></em>; and performs in them competitively, aiming to further (what he perceives as) his own interests.</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 16:17, 29 October 2023

Contents

Federation through Keywords

(Ulrich Beck, The Risk Society and Beyond, 2000)

Imagine us in “the risk society”—impregnated with existential risks we don’t know how to handle; we shall not move beyond the risk society—as long as we look at those problems through the same concepts we used when we created them.

The first and most important thing you want to know about these keywords is that they are custom-defined ways of looking or technically scopes; when I turn for instance culture into a keyword—I am not defining what culture "really is"; but giving you a way to look at the infinitely complex real thing; and producing a sort of a projection plane, to greatly simplify the matter. The point is that we can only see things whole if we look at them from all sides; and that if we can discover a way of looking that shows the thing as not whole—then the thing is not whole even when by "normal" way of looking it does look perfectly fine.

Keywords elevate us 'on the shoulders of giants' so we may see further.

As custom-defined words, keywordsenable us to think and speak in new ways. By creating keywords we can give old words such as “science” and “religion” a distinct function and a new life; keyword creation is a means to linguistic and institutional recycling.

When adopted from the terminology of an academic field, cultural tradition or frontier thinker, keywords enable us to account for what’s been seen, experienced or comprehended; to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’ and see further; to see things in new ways and see them whole.

Paradigm

I use the word paradigm informally—to point to a general societal and cultural order of things; where everything depends on everything else; and also more formally as Thomas Kuhn did—to point to a (1) different way to conceive of a certain domain of interest, which (2) resolves the reported anomalies and (3) opens up a new frontier for research and development.

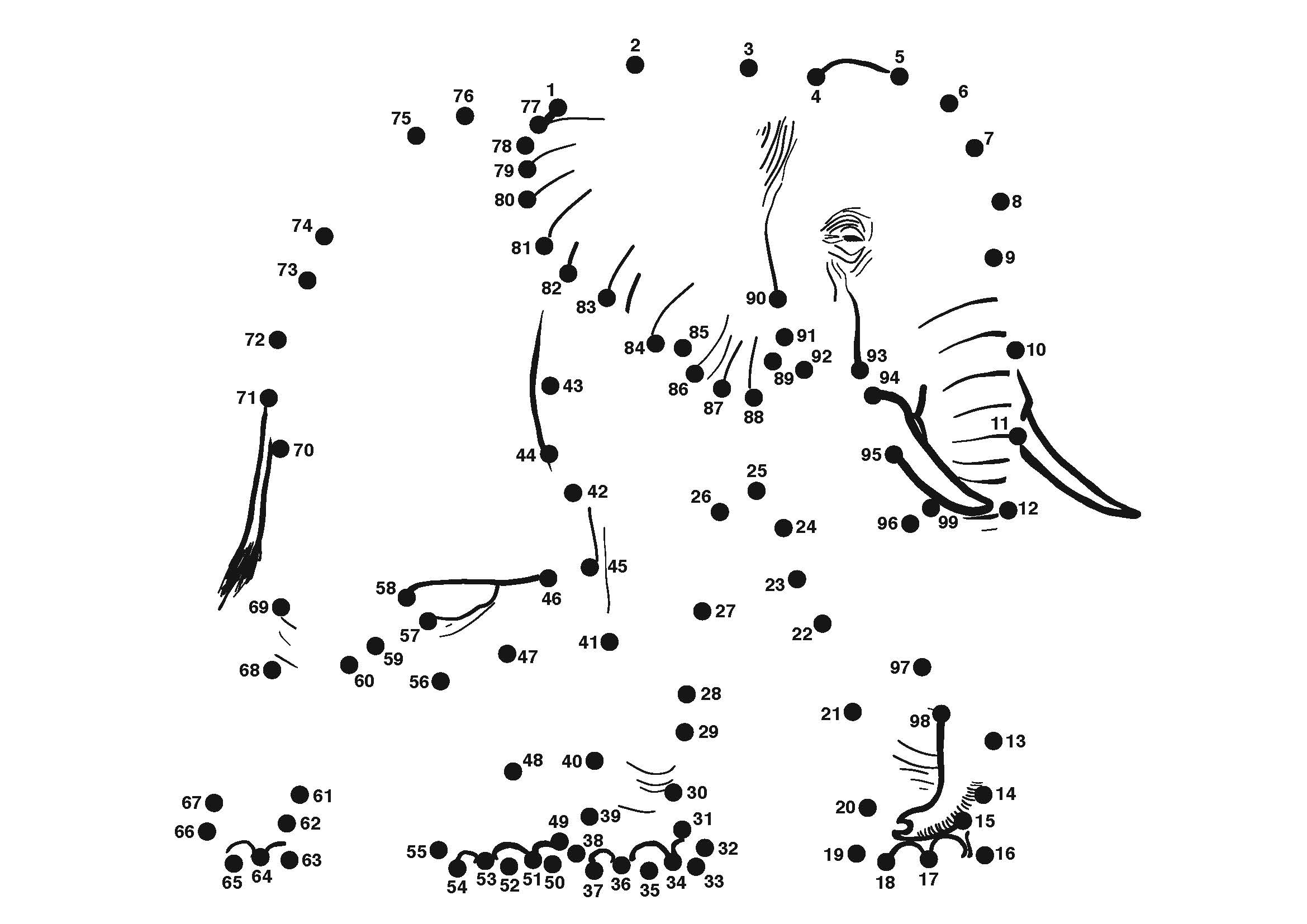

The Liberation book begins with the iconic image of Galilei in house arrest whispering "And yet it moves!"; and develops an analogy—between that historical moment when a sweeping paradigm shift was about to happen (from the Middle Ages and tradition, to the Enlightenment and Modernity) and our own time; where the paradigm is again ready to shift; because the reported anomalies demand that it does; and because we already own the information that comprehensive change requires.

It remains to 'connect the dots'.

Logos

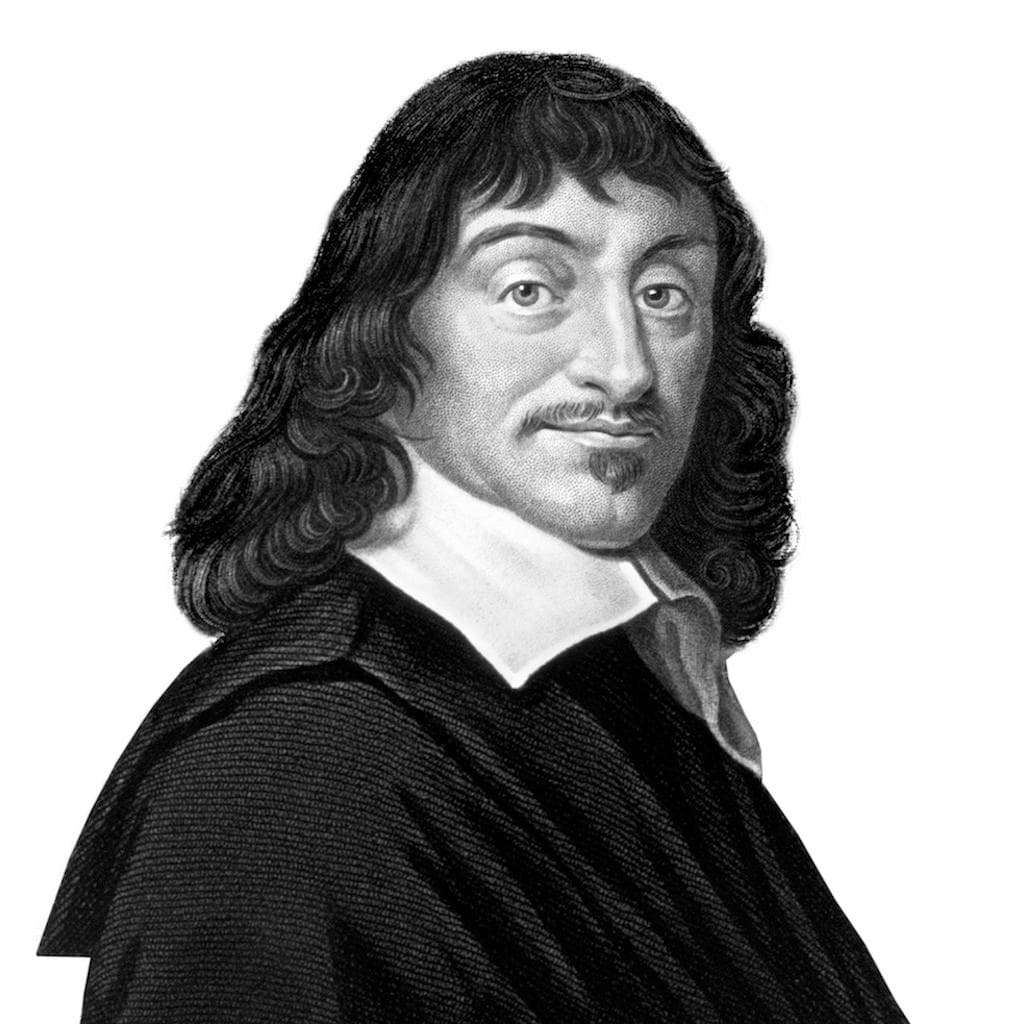

(René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, 1641)

The reason why we must do as Descartes did—and "demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations"—is that he and his Enlightenment comrades got it all wrong!

"In the beginning was logos and logos was with God and the logos was God." I use logos as keyword to point to this reconstruction because it helps us comprehend what exactly went wrong and why. To the philosophers of antiquity, "logos" was the principle according to which God structured the world; which enables us humans to comprehend the world and dance with it harmoniously. How and why this is at all possible—here the opinions differed; and gave rise to a wealth of stream of thought and cultural directions. But "logos" did rather poorly from then on; it did not translate well into Latin; and during the Middle Ages it was believed that logos was revealed to us humans through God's own son; and so was all further quest of logos forgotten or even forbidden.

Descartes and his colleagues revived it—but conceived it as the quest for "objective" and unchanging truth; which is, they took this for granted, revealed to the mind as the sensation of absolute certainty. You'll now easily comprehend how from that point on everything went wrong: Instead of conscientiously looking at things from all sides in order to see them whole—we ended up getting stuck with whatever way of looking at things there was that gave the mind that comforting sensation; and we ignored whatever might threaten it!

Seduced by reductionistic comprehension—we failed to even notice when knowledge became impossible.

In the Liberation book this is made transparent already in Chapter Two; where I tell the thread (short sequence of vignettes) where Nietzsche first portrays us modern humans (at the turn of the twentieth century!) as (already!) overwhelmed by "the abundance of disparate impressions" and "the tempo of [their] influx"; so that we "instinctively resists taking in anything, taking anything deeply"; and "unlearn spontaneous action [and] merely react to stimuli from outside". How do we cope with the overabundance of data (made to stimulate and not help us comprehend) on one side, and the staggering complexity of our world on the other, I asked; and let Anthony Giddens give an answer: “The threat of personal meaninglessness is ordinarily held at bay because routinised activities, in combination with basic trust, sustain ontological security. Potentially disturbing existential questions are defused by the controlled nature of day-to-day activities within internally referential systems." Are you beginning to see how materialism<b>—our modernity's present <b>paradigm</b>—naturally emerged from this foundation? In the book I summed this up by adapting (Johan Huizinga's) <b>homo ludens</b> as <b>keyword</b>; and calling it a 'cultural species, which (unlike the cultural <b>homo sapiens</b> who seeks <b> knowledge</b> to choose directions) simply learns 'the rules of the game' of one's profession and other society's <b>systems</b>; and performs in them competitively, aiming to further (what he perceives as) his own interests.</p>

</div>

</div>