Holotopia: Collective mind

Contents

- 1 H O L O T O P I A: F I V E I N S I G H T S

- 2 Collective mind

- 2.1 Stories

- 2.2 The Wiener's paradox

- 2.3 The academic big question

- 2.4 Our collective mind is just plain insane

- 2.5 The cultural big question

- 2.6 Ideogram

- 2.7 Keywords

- 2.8 Ideogram

- 2.9 Knowledge federation

- 2.10 Transdiscipline

- 2.11 Prototype

- 2.12 Bootstrapping

- 2.13 Prototypes

- 2.14 Information holon

- 2.15 Knowledge Federation

- 2.16 TNC2015

- 2.17 BCN2011

H O L O T O P I A: F I V E I N S I G H T S

Collective mind

The printing press revolutionized communication, and enabled the Enlightenment. But we too are witnessing a similar revolution—the advent of the Internet, and the interactive digital media. Are we really calling that a pair of candle headlights?

We look at the way in which this new technology is being used. And at the principle of organization that underlies this use. Without noticing, we have adopted a principle of organization that suited the old technology, the printing press—broadcasting. But the new technology, by linking us together in a similar way as the nervous system links the cells in an organism, enables and even demands completely new modalities of organization. Imagine if your own cells were using your nervous system to merely broadcast data! In a collective mind, broadcasting leads to collective madness—and not to "collective intelligence" as the creators of the new technology intended.

Stories

The Wiener's paradox

The root of the paradox is that the system is broken (our 'bus' does not have proper 'headlights' or 'steering'), i.e. structured so that it is incapable of using information to steer (as Wiener pointed out, already in 1948).

The resolution to the paradox is bootstrapping—co-creating new systems, with our own minds and bodies.

The academic big question

Consider the academia as a system: It has a vast heritage to take care of, and make use of. Selected creative people come in. They are given certain tools to work with, certain ways how to work, certain communication tools that will take their results and turn them into socially useful effect. How effective, and efficient, is the whole thing as a system? Is it taking advantage of the invaluable (especially in this time when our urgent need is creative change) resources that have been entrusted to it?

Enter information technology...

The big point here is that the academia's primary responsibility or accountability is for the system as a whole, and for each of its components. The academia had an asset, let's call him Pierre Bourdieu. This person was given a format to write in—which happened to be academic books and articles. He was given a certain language to express himself in. How good are those tools? Could there be answers to this question (which the academi has, btw, not yet asked in any real way) that are incomparably, by orders of magnitude, better than what the academia of his time afforded to Bourdieu? And to everyone else, of course.

Analogy with the history of computer programming

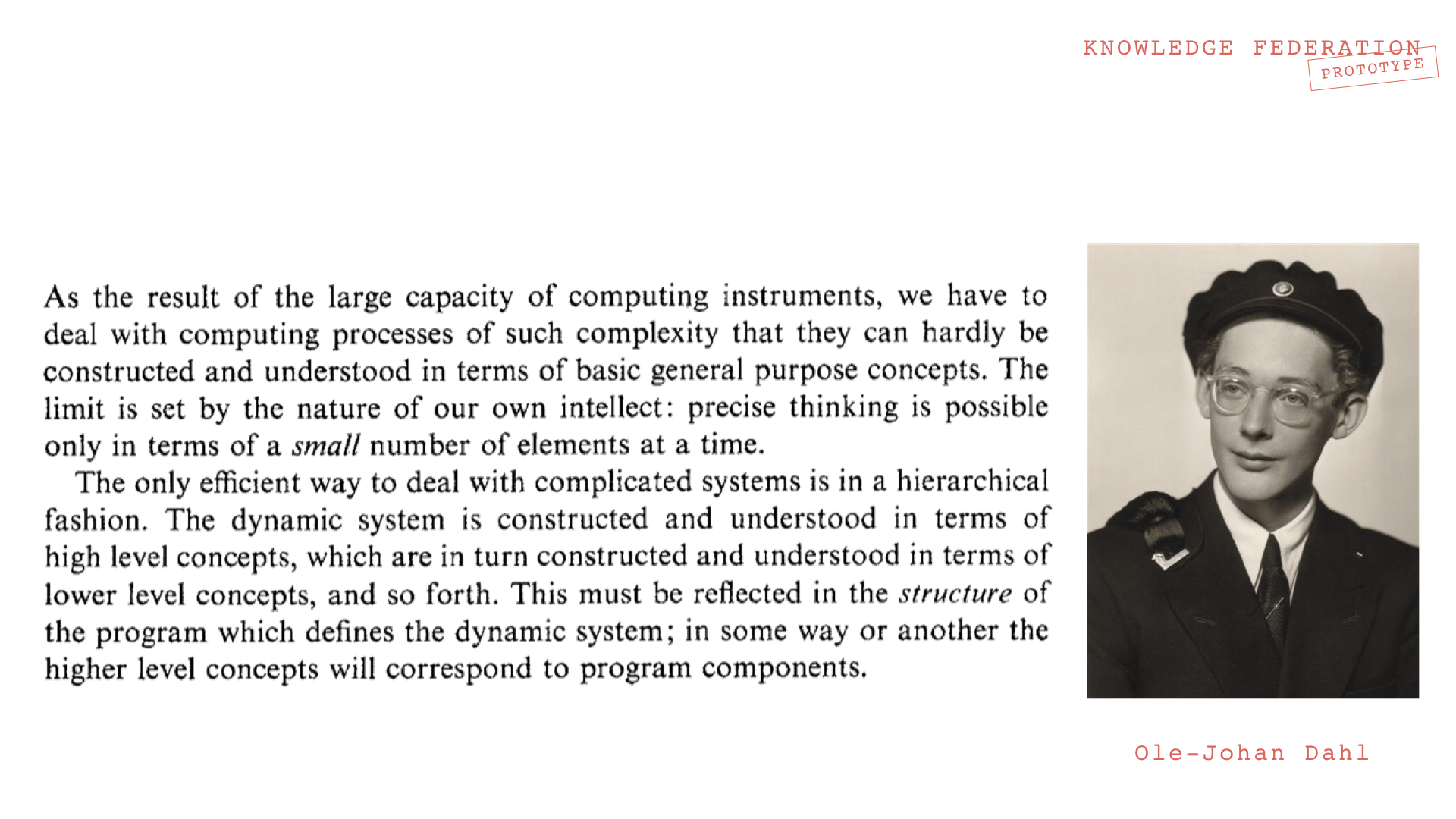

We point to the analogy between the situation in computer programming following the advent of the computer, in response to which computer programming methodologies were developed—and the situation in our handling of information following the advent of the Internet. In the first years of computing, ambitious software projects were undertaken, which resulted in "spaghetti code"—a tangled up mess of thousands of lines of code, which nobody could understand, detangle and correct. The programmers were coming in and out of those projects, and those who stepped in later had to wonder whether to throw the whole thing away and begin from scratch—or to continue to try to correct it.

A motivating insight that needs to be drawn from this history is that a dramatic increase in size of the thing being handled (computer programs and information) can not be effectively responded to by merely more of the same. A structural change (a different paradigm) is what the situation is calling for.

A new paradigm is needed

Edsger Dijkstra, one of the pioneers of the development of methodologies, argued that programming in the large is a completely different thing than programming in the small (for which textbook examples and the programming tools at large were created at the time):

“Any two things that differ in some respect by a factor of already a hundred or more, are utterly incomparable.”

Doug Engelbart used to make the same point (that the increase in size requires a different paradigm) by sharing his parable of a man who grew ten times in size (read it here).

The key point

The solution was found in developing structuring and abstraction concepts and methodologies (as we summarized here). Among them, the Object Oriented Methodology is the best known example.

The key insight to be drawn from this analogy: computers can be programmed in any programming language. The creators of the programming methodologies, however, took it as their core challenge, and duty, to give the programmers the conceptual and technical tools that would coerce them to write code that is comprehensible, maintainable and reusable. The Object Oriented Methodology responds to this challenge by conceiving of computer programming as modeling of complex systems—in terms of a hierarchy of "objects". An object is a structuring device whose purpose is to "export function" (make a set of functions available to higher-order objects), and "hide implementation".

Without yet recognizing this, the academia now finds itself in a similar situation as the creators of computer programming methodologies. The importance of finding a suitable response to this challenge cannot be overrated.

Implications for cultural revival

There is also an interesting difference between computer programming and handling of information: The fact that a team of programmers can no longer understand the program they are creating is easily detected—the program won't run on the computer; but how does one detect the incomparably larger and more costly problem—that a generation of people can no longer comprehend the information they own? And hence the situation they are in?

Our collective mind is just plain insane

The Incredible History of Doug

The most wonderful story, however, is without The Incredible History of Doug (Engelbart), introduced by the story of Vannevar Bush. This story will be federated in the book "Systemic Innovation" (subtitle "The Future of Democracy"), which is the second book we are preparing as part of the tactics for launching the Holotopia project.

What more to say about the fact that Vannevar Bush, as the academic strategist par excellence, identified the problem we are talking with as the problem the scientists must focus on and resolve—already in 1945? And that Douglas Engelbart understood that (well beyond what Bush anticipated) digital computers, when equipped with interactive terminals and joined into a network, can serve as in effect a collective nervous system—and enable incomparably better ways to respond to the "complexity times urgency" issue, that underlies the humanity's contemporary challenges. See our summary here. This short video introduces The Incredible History of Doug, this one explains his vision.

It remains to highlight the main point.

A collective mind, combined with broadcasting (the process we've inherited from the printing press), spells collective madness—and not "collective intelligence" as Engelbart, and also Bush, intended.

What if

There are quite a few pieces of anecdotal evidence, and even some theoretical ones, that suggest that real or systemic or outside of the box creativity, as well as our comprehension of complex matters, depend on a slow, annealing-like process, which requires a relaxed and defocused state of mind (some of them were discussed in the blog post Tesla and the Nature of Creativity).

Here is an ad-hoc possibility.

A frog leaps and catches a passing fly. Had the fly been still, the frog would not have noticed it.

Already very primitive organisms have adapted, through the survival of the fittest, to pay attention to movement and to changes of light and shadow—that being an easy way to detect food, and predators. What if the contemporary media keep us captive by taking advantage of some similarly primitive properties of our mechanism of perception?

"The average length of a shot on network television is only 3.5 seconds, so that the eye never rests, always has something new to see", Postman observed in "Amusing Ourselves to Death".

Have we developed a lifestyle that precludes such creativity, and comprehension?

Has "a great cultural revival" become a cultural impossibility?

The cultural big question

Here we may begin from the archetypal image, of a mother by the bedside or a grandfather by a fire place, telling kids the stories of old... In focus here are cultural reproduction... and human quality... in the age of ubiquitous and pervasive digital media.

Nietzsche already warned us

Already Nietzsche warned us that the overabundance of impressions that modernity has give us keeps us dazzled, unable to digest and to act, but merely reacting... See Intuitive introduction to systemic thinking.

Neil Postman studied this issue academically, and thoroughly.

At NYU, where he chaired the Department of Culture and Communication, he created a graduate program in "media ecology"—and by naming it thus put his finger exactly at the sore spot.

Postman's best known work, his 1985 book "Amusing Ourselves to Death", is a careful argument showing... well, here is a summary by his son, Andrew Postman, in the introduction he wrote for the 20th anniversary edition:

Is it really plausible that this book about how TV is turning all public life (education, religion, politics, journalism) into entertainment; how the image is undermining other forms of communication, particularly the written word; and how our bottomless appetite for TV will make content so abundantly available, context be damned, that we'll be overwhelmed by "information glut" until what is truly meanmingful is lost and we no longer care what we've lost as long as we're being amused. ... Can such a book possibly have relevance to you and The World of 2006 and beyond?

Guy Debord saw that this issue was political

The technical keyword here is "alienation" (Debord operated within the ideological framwork of neo-Marxism), but Debord's insights are invaluable, and need to be federated. Seen within the power structure and symbolic reality framework, they will be (we anticipate) be a lot more easy to digest for a contemporary reader.

But yes, his point–it is that the addictive effect the new media have on us must be seen, and handled, as a key means of disempowerment. His "Society of the Spectacle" has lately been drawing increased attention—see this commentary in the Guardian, and this video where Debord's work is introduced as a "critique of a society which he saw as being ever more obsessed with images and appearances, over reality, truth and experience".

Is "human quality" eroded by the new media.

And what is to be done about that?

We need to look at ourselves in the mirror

The deeper underlying question is the one of academic self-identity.

Wll the academia remain "an objective observer" of all the structural changes in our cultural reproduction that are going on? Or will it take a proactive stance?

Ideogram

Our civilization is like an organism that has recently grown beyond bounds ("exponentially")—and now represents a threat to its environment, and to itself. By a most fortunate mutation, this creature has recently developed a nervous system, which could allow it to comprehend the world and coordinate its actions. But the creature is using it only to amplify its most primitive, limbic impulses.

Keywords

Ideogram

Placeholder—for a variety of techniques that can be developed by using contemporary media technology. The point here is to condense lots and lots of insights into something that communicates them most effectively—which can be a poem, a picture, a video, a movie....

Instead of using media tools addictively, and commercially, we use them to rebuild the culture—as people have done through ages. The difference is made by the knowledge federation infrastructure—which secures that what needs to be federated gets federated.

Knowledge federation

We use this keyword, knowledge federation, in a similar way as "design" and "architecture" are commonly used—to signify both a set of activities, and an academic field that develops them.

As a set of activities, knowledge federation can now be understood as the workings of a well-functioning collective mind. Instead of broadcasting, the cells and organs (researchers, disciplines, communities...) process the information they are handling and dispatch suitably prepared pieces to suitable other cells and organs. The prefrontal lobe receives what it needs. And so do the muscles. In the development of a collective mind that federates knowledge, the cells self-organize, specialize, develop completely new goals, processes, ways of working...

How does it all work? 'Programming' our collective mind is what knowledge federation as transdiscipline is all about. It draws insights from all relevant fields—and weaves them into the very functioning of our collective mind. Yes, this is roughly what philosophy was or appeared to be all about, in the old paradigm.

As an academic field, knowledge federation develops the praxis of knowledge federation. There is phenomenally much to be done—since everything that the tradition has given us and we customarily take for granted (all those 'candles'...) now need to be reassessed and reconfigured.

In the analogy with computer programming, knowledge federation roughly corresponds to object orientation. Here is how Old-Johan Dahl, one of the creators of the Object Oriented Methodology, described the underlying idea.

Transdiscipline

Roughly corresponds to the discipline.

Prototype

Enable knowledge federation and give agency—by forming a transdiscipline around a prototype.

Bootstrapping

Enables knowledge federation to overcome its basic obstacle, the Wiener's paradox—instead of merely writing and observing, we co-create systems by using our own bodies and minds as material.

As Engelbart rightly observed, bootstrapping is the key next step in the collective mind re-evolution.

Prototypes

Information holon

Roughly corresponds to "object".

Knowledge Federation

prototype of "the transdiscipline for knowledge federation. Modeled by analogy with an academic discipline—to contain everything from epistemological underpinnings and methodology, to social processes and institutional organization. All very different, of course, adapted to the needs of transdisciplinary work, and knowledge federation.

TNC2015

Tesla and the Nature of Creativity (TNC2015) is a complete example of knowledge federation in academic communication—shows how a research result is federated. See the Tesla and the Nature of Creativity and A Collective Mind – Part One blog posts.

BCN2011

The Barcelona Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism (BCN2011) is a complete prototype showing how public informing can be reconstructed, to federate the most relevant information, according to the needs of people and society. A description with links is provided here.