Difference between revisions of "Holotopia"

m |

m |

||

| (304 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | <div class="page-header" ><h1> | + | <div class="page-header" ><h1>HOLOTOPIA</h1><br><br><h2>An Actionable Strategy</h2></div> |

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-3"><h2>Our proposal</h2></div> | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Our proposal</h2></div> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-6"> | + | <div class="col-md-6"> |

| − | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

The core of our [[Holotopia:Knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]] proposal is to change the relationship we have with information. | The core of our [[Holotopia:Knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]] proposal is to change the relationship we have with information. | ||

| Line 30: | Line 28: | ||

"The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it." | "The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it." | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="col-md-3"> | <div class="col-md-3"> | ||

| Line 38: | Line 36: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-3"></div> | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-7" | + | <div class="col-md-7"> |

| − | + | <p>What would information and our handling of information be like, if we treated them as we treat other human-made things—if we adapted them to the purposes that need to be served? </p> | |

| − | <p>What would information and our handling of information be like, if we treated | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <p>By what methods, what social processes, and by whom would information be created? What new information formats would emerge, and supplement or replace the traditional books and articles? How would information technology be adapted and applied? What would public informing be like? And <em>academic communication, and education</em>? </p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The substance of our proposal is a <em>complete</em> [[Holotopia:Prototype|<em>prototype</em>]] of [[Holotopia:Knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]], where initial answers to relevant questions are proposed, and in part implemented in practice. </blockquote> |

| − | <blockquote>Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop <em>knowledge federation</em> as an academic field, and | + | <blockquote>Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop <em>knowledge federation</em> as an academic field, and a real-life <em>praxis</em> (informed practice).</blockquote> |

| + | <blockquote>Our purpose is to restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.</blockquote> | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>A proof of concept application</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"> | ||

| + | <p>The Club of Rome's assessment of the situation we are in, provided us with a benchmark challenge for putting the proposed ideas to a test.</p> | ||

| − | + | <p>Four decades ago—based on a decade of this global think tank's research into the future prospects of mankind, in a book titled "One Hundred Pages for the Future"—[[Aurelio Peccei]] issued the following call to action: </p> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

"It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course." | "It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course." | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ||

<p>Peccei also specified <em>what</em> needed to be done to "change course":</p> | <p>Peccei also specified <em>what</em> needed to be done to "change course":</p> | ||

| Line 77: | Line 72: | ||

<div class="col-md-3"></div> | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

<div class="col-md-7"> | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| − | <p>This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century's thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology". </p> | + | <p>This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century's thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology". In what follows we shall assume that this conclusion has been <em>federated</em>—and focus on the more interesting questions, such as <em>how</em> to "change course"; and in what ways may the new course be different.</p> |

<p>In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:</p> | <p>In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:</p> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| Line 85: | Line 80: | ||

The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".</p> | The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".</p> | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote>Could the change of 'headlights' we are proposing be "a way to change course"?</blockquote> |

| − | < | + | </div> </div> |

| − | |||

| − | <blockquote> | + | <div class="row"> |

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>A vision</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <blockquote><em>Holotopia</em> is a vision of a possible future that emerges when proper 'light' has been 'turned on'.</blockquote> | ||

| + | <p>Since Thomas More coined this term and described the first utopia, a number of visions of an ideal but non-existing social and cultural order of things have been proposed. But in view of adverse and contrasting realities, the word "utopia" acquired the negative meaning of an unrealizable fancy.</p> | ||

| + | <p>As the optimism regarding our future waned, apocalyptic or "dystopian" visions became common. The "protopias" emerged as a compromise, where the focus is on smaller but practically realizable improvements.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The <em>holotopia</em> is different in spirit from them all. It is a <em>more</em> attractive vision of the future than what the common utopias offered—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not yet exist. And yet the <em>holotopia</em> is readily actionable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.</p> | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The <em>holotopia</em> vision is made concrete in terms of <em>five insights</em>, as explained below.</blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| Line 101: | Line 99: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>A | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>A principle</h2></div> |

| − | <div class="col-md-7" | + | <div class="col-md-7"> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <p><em>What do we need to do</em> to "change course" toward the <em>holotopia</em>?</p> | |

| − | + | <blockquote>The <em>five insights</em> point to a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things [[Wholeness|<em>whole</em>]].</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | <p><em>What do we need to do</em> to change course toward the <em>holotopia</em>?</p> | ||

| − | <blockquote> | ||

<p>This principle is suggested by the <em>holotopia</em>'s very name. And also by the Modernity <em>ideogram</em>. Instead of <em>reifying</em> our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the [[Wholeness|<em>wholeness</em>]] of it all. </p> | <p>This principle is suggested by the <em>holotopia</em>'s very name. And also by the Modernity <em>ideogram</em>. Instead of <em>reifying</em> our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the [[Wholeness|<em>wholeness</em>]] of it all. </p> | ||

| Line 118: | Line 110: | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>A method</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <p>"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost <em>the sense of the whole</em>." </p> | ||

| + | <blockquote>To make things [[Wholeness|<em>whole</em>]]—<em>we must be able to see them whole</em>! </blockquote> | ||

| + | <p>To highlight that the <em>knowledge federation</em> methodology described and implemented in the proposed <em>prototype</em> affords that very capability, to <em>see things whole</em>, in the context of the <em>holotopia</em> we refer to it by the pseudonym <em>holoscope</em>. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>While the characteristics of the <em>holoscope</em>—the design choices or <em>design patterns</em>, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.</p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<p> | <p> | ||

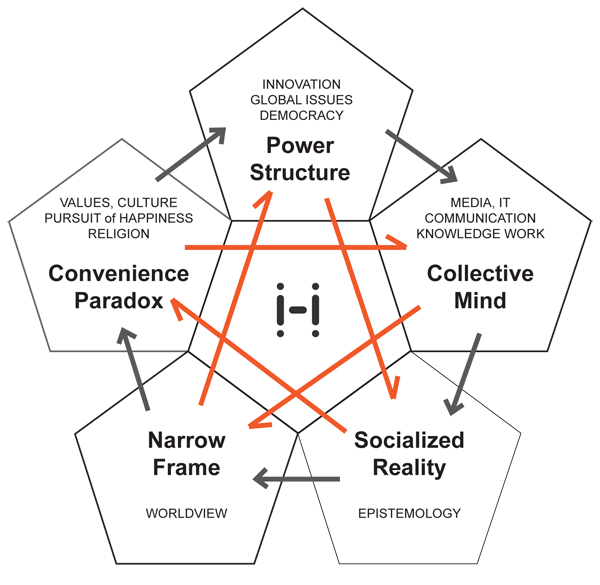

[[File:Holoscope.jpeg]]<br> | [[File:Holoscope.jpeg]]<br> | ||

<small>Holoscope <em>ideogram</em></small> | <small>Holoscope <em>ideogram</em></small> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | + | ||

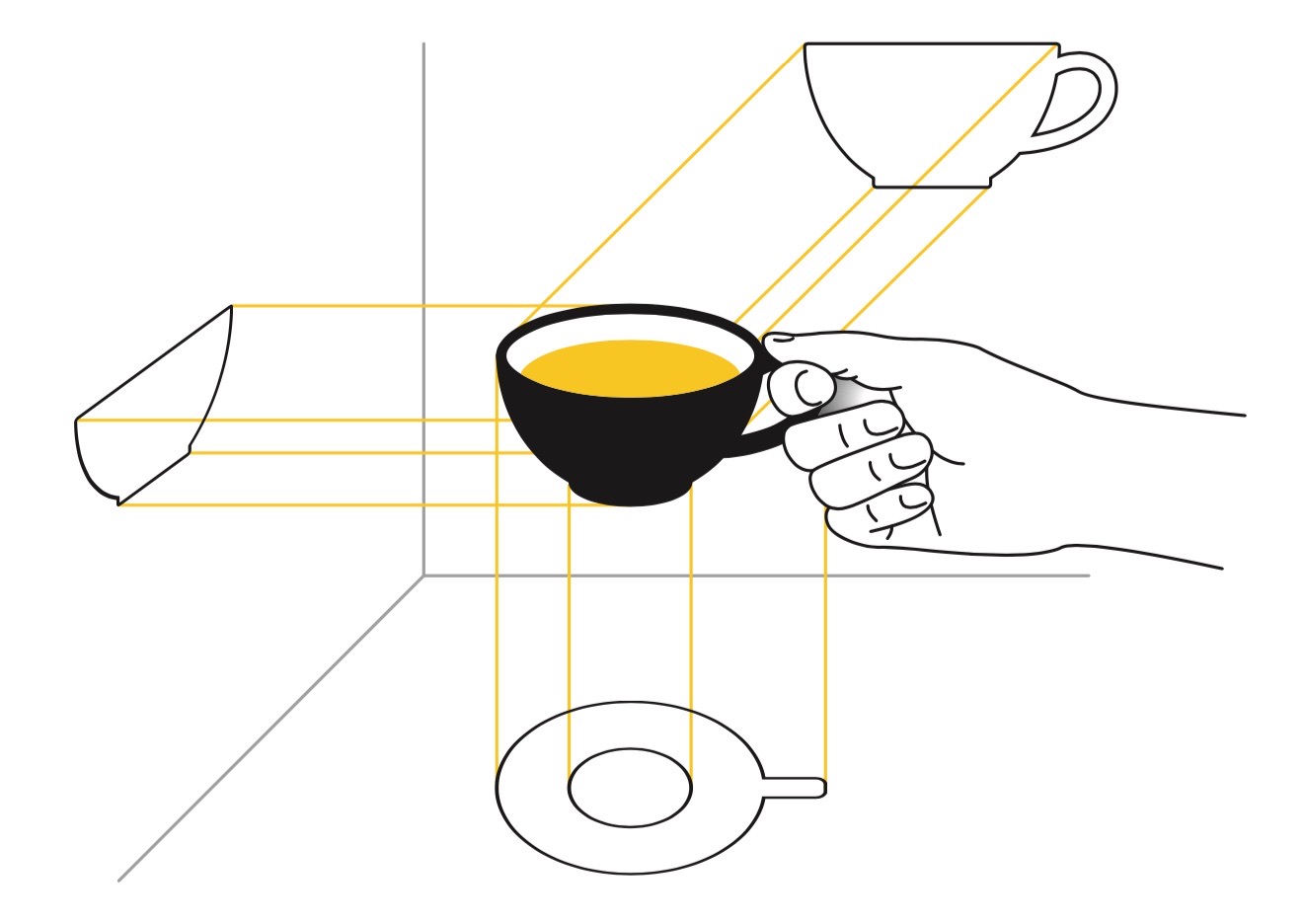

<blockquote>To see things whole, we must look at all sides.</blockquote> | <blockquote>To see things whole, we must look at all sides.</blockquote> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The <em>holoscope</em> distinguishes itself by allowing for <em>multiple</em> ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called <em>scopes</em>. The <em>scopes</em> and the resulting <em>views</em> have similar meaning and role as projections do in technical drawing.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>This <em>modernization</em> of our handling of information—distinguished by purposeful, free and informed <em>creation</em> of the ways in which we look at the world—has become <em>necessary</em> in our situation, suggests the bus with candle headlights. But it also presents a challenge to the reader—to bear in mind that the resulting views are not "reality pictures", contending for that status with our conventional ones.</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>In the <em>holoscope</em>, the legitimacy and the peaceful coexistence of multiple ways to look at a theme is axiomatic.</blockquote> |

| − | < | + | <p>We will continue to use the conventional way of speaking and say that something <em>is</em> as stated, that <em>X</em> <em>is</em> <em>Y</em>—although it would be more accurate to say that <em>X</em> can or must (also) be perceived as <em>Y</em>. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way (to use the offered <em>scopes</em>); and to do that collaboratively, in a [[dialog|<em>dialog</em>]].</p> |

| − | <p>To liberate our | + | |

| + | <p>To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of <em>scopes</em>, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy. </p> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the <em>tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention</em>. The <em>holoscope</em> is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see <em>any</em> chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion. | Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the <em>tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention</em>. The <em>holoscope</em> is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see <em>any</em> chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion. | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| + | <p>A discovery of a new way of looking—which reveals a structural problem, and helps us reach a correct general assessment of an object of study or a situation as a whole (see whether the 'cup' is 'broken' or 'whole') is a new <em>kind of result</em> that is made possible by th general-purpose science that is modeled by the <em>holoscope</em></p> | ||

| + | <p>To see more, we take recourse to the vision of others. The <em>holoscope</em> combines scientific and other insights to enable us to see what we ignored, to 'see the other side'. This allows us to detect structural defects ('cracks') in core elements of everyday reality—which appear to us as just normal, when we look at them in our habitual way ('in the light of a candle'). </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>All elements in our proposal are deliberately left unfinished, rendered as a collection of <em>prototypes</em>. Think of them as composing a 'cardboard model of a city', and a 'construction site'. By sharing them we are not making a case for a specific 'city'—but for 'architecture' as an academic field, and a real-life <em>praxis</em>. </p> | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<div class="page-header" ><h2>Five insights</h2></div> | <div class="page-header" ><h2>Five insights</h2></div> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2></h2></div> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em>Scope</em></h2></div> |

<div class="col-md-7"> | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>What is wrong with our present "course"? In what ways does it need to be changed? What benefits will result?</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

<p> | <p> | ||

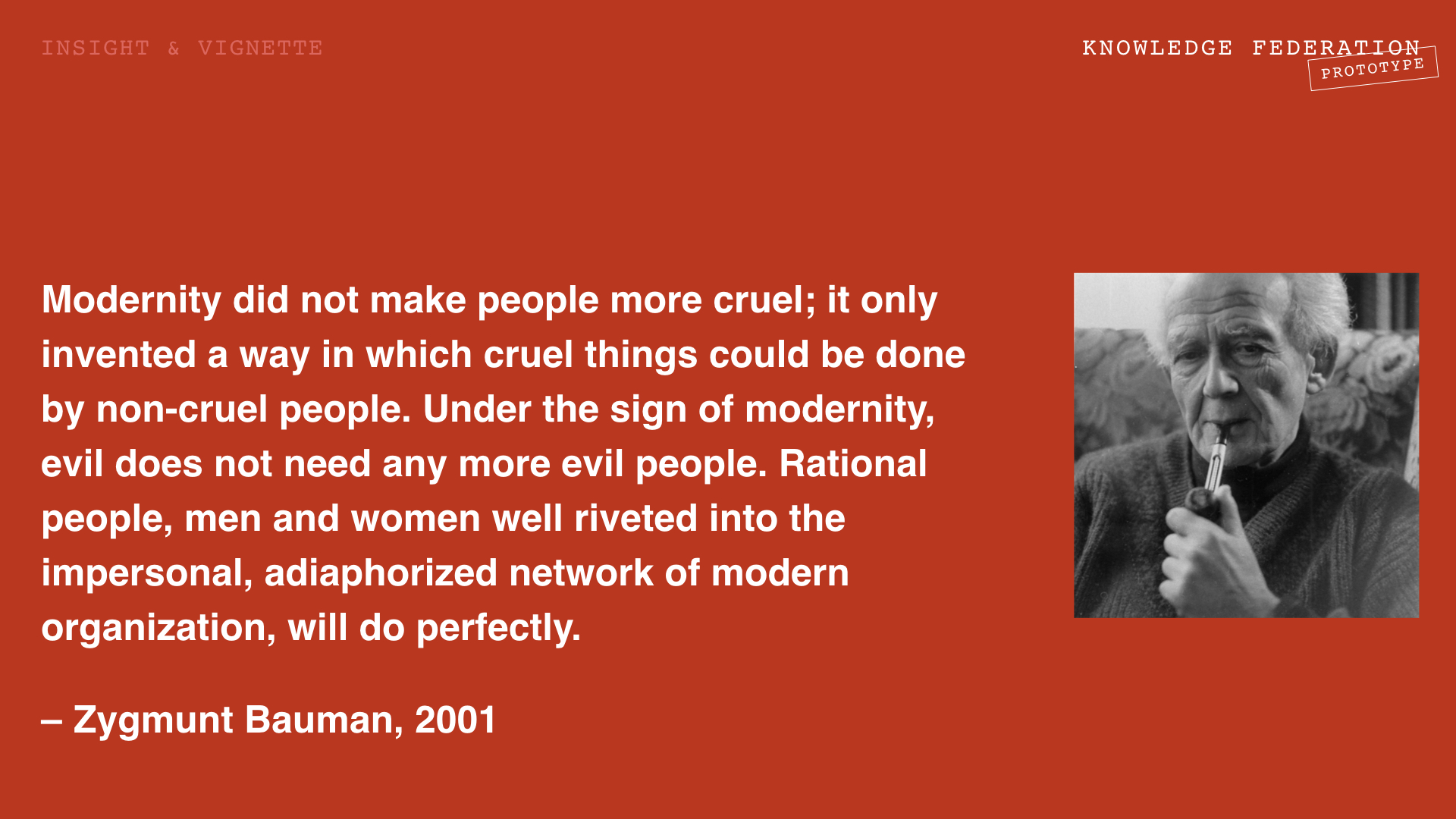

[[File:FiveInsights.JPG]]<br> | [[File:FiveInsights.JPG]]<br> | ||

<small>Five Insights <em>ideogram</em></small> | <small>Five Insights <em>ideogram</em></small> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>We use the <em>holoscope</em> to illuminate five <em>pivotal</em> themes, which <em>determine</em> the "course":</p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

| − | <li>Innovation | + | <li><b>Innovation</b>—the way we use our ability to create, and induce change</li> |

| − | <li>Communication | + | <li><b>Communication</b>—the social process, enabled by technology, by which information is handled</li> |

| − | <li>Epistemology | + | <li><b>Epistemology</b>—the fundamental assumptions we use to create truth and meaning; or "the relationship we have with information"</li> |

| − | <li>Method | + | <li><b>Method</b>—the way in which truth and meaning are constructed in everyday life, or "the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it"</li> |

| − | <li>Values | + | <li><b>Values</b>—the way we "pursue happiness", which in the modern society <em>directly</em> determines the course</li> |

| − | </ul> | + | </ul> |

| − | <p> | + | |

| + | <p>In each case, we see a structural defect, which led to perceived problems.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>Those structural defects <em>can</em> be remedied.</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Their removal naturally leads to improvements that are well beyond the removal of symptoms.</p> | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The <em>holotopia</em> vision results.</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The key to comprehensive change is the same as it was in Galilei's time—a method that allows for creation of general principles and insights. But since "a great cultural revival" is our next goal, this new method allows for the creation of insights <em>about the most basic themes that mark our social and private existence</em>. </p> |

| − | |||

| + | <blockquote>A case for our proposal is thereby also made.</blockquote> | ||

| + | <p>In the spirit of the <em>holoscope</em>, we here only summarize the <em>five insights</em>—and provide evidence and details separately.</p> | ||

| + | </div> </div> | ||

| Line 193: | Line 198: | ||

<h3><em>Scope</em></h3> | <h3><em>Scope</em></h3> | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote><em><b>What</b> do we need to do</em>, to become capable of "changing course"?</blockquote> |

| − | < | + | <p>"Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it", observed Peccei. Imagine if some malevolent entity, perhaps an insane dictator, took control over that power. </p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The [[Power structure|<em>power structure</em>]] insight shows that no dictator is needed.</blockquote> |

| − | + | <p>Albeit in democracy, we are in that situation <em>already</em>.</p> | |

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <p>While the nature of the <em>power structure</em> will become clear as we go along, imagine it, to begin with, as our institutions; or more accurately, as <em>the systems in which we live and work</em> (which we simply call <em>systems</em>).</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Notice that <em>systems</em> have an <em>immense</em> power—<em>over us</em>, because <em>we have to adapt to them</em> to be able to live and work; and <em>over our environment</em>, because by organizing us and using us in a certain specific way, <em>they decide what the effects of our work will be</em>. </p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The <em>power structure</em> determines whether the effects of our efforts will be problems, or solutions. </blockquote> |

| − | < | + | <h3>Diagnosis</h3> |

| − | < | + | <p>How suitable are <em>the systems in which we live and work</em> for their all-important role?</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>Evidence shows that they waste a lion's share of our resources. And that they either <em>cause</em> problems, or make us incapable of solving them.</blockquote> |

| − | < | + | <p>The root cause of this malady is readily found in the way in which <em>systems</em> evolve. </p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>Survival of the fittest favors the <em>systems</em> that are predatory, not the ones that are useful. </blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>[https://youtu.be/zpQYsk-8dWg?t=920 This excerpt] from Joel Bakan's documentary "The Corporation" (which Bakan as a law professor created to <em>federate</em> an insight he considered essential) explains how the most powerful institution on our planet evolved to be a perfect "externalizing machine" ("Externalizing" means maximizing profits by letting someone else bear the costs, notably the people and the environment), just as the shark evolved to be a perfect predator. [https://youtu.be/qsKQiVJkEvI?t=2780 This scene] from Sidney Pollack's 1969 film "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" will illustrate how the <em>power structure</em> affects <em>our own</em> condition.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The <em>systems</em> provide an ecology, which in the long run shapes our values, and our "human quality". They have the power to <em>socialize</em> us in ways that suit <em>their</em> needs. "The business of business is business"—and if our business is to succeed in competition, we <em>must</em> act in a certain way. We either bend and comply—or get replaced. The effect on the <em>system</em> will be the same.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

<p> | <p> | ||

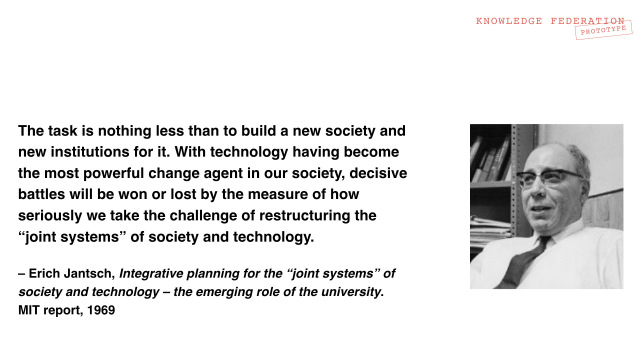

[[File:Bauman-PS.jpeg]] | [[File:Bauman-PS.jpeg]] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <p>A | + | <p>A consequence, Zygmunt Bauman diagnosed, is that bad intentions are no longer needed for bad things to happen. Through <em>socialization</em>, the <em>power structure</em> can co-opt our duty and commitment; and even our heroism and honor.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Bauman's insight that even the holocaust was only a consequence and a special case, however extreme, of (what we are calling) the <em>power structure</em>, calls for careful contemplation: Even the concentration camp employees, Bauman argued, were only "doing their job"—in a <em>system</em> whose nature and purpose was beyond their ethical sense, and power to change. </p> |

| − | <blockquote>Our | + | <p>While our ethical sensitivity is tuned to the <em>power structures</em> of the past, we are committing (in all innocence, by acting through the <em>power structures</em> that bind us together) the greatest [https://youtu.be/d1x7lDxHd-o massive crime] in human history.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>Our children may not have a livable planet to live on.</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Not because someone broke the rules—<em>but because we follow them</em>.</p> | ||

<h3>Remedy</h3> | <h3>Remedy</h3> | ||

| − | <p>The fact that we will not "solve our problems" unless we | + | <p>The fact that we will not "solve our problems" unless we develop the capability to update our <em>systems</em> has not remained unnoticed. </p> |

<p> | <p> | ||

| Line 243: | Line 245: | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <p>The very first step the | + | <p>The very first step that the The Club of Rome's founders did after its inception, in 1968, was to convene a team of experts, in Bellagio, Italy, to develop a suitable methodology. They gave "making things whole" on the scale of socio-technical systems the name "systemic innovation"—and we adapted that as one of our <em>keywords</em>. </p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>The work and the conclusions of this team were based on results in the systems sciences. More recently, in "Guided Evolution of society", systems scientist Béla H. Bánáthy made a thorough review of relevant research, and concluded in a truly <em>holotopian</em> tone:</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>We are the <em>first generation of our species</em> that has the privilege, the opportunity and the burden of responsibility to engage in the process of our own evolution. We are indeed <em>chosen people</em>. We now have the knowledge available to us and we have the power of human and social potential that is required to initiate a new and historical social function: conscious evolution. But we can fulfill this function only if we develop evolutionary competence by evolutionary learning and acquire the will and determination to engage in conscious evolution. These two are core requirements, because <em>what evolution did for us up to now we have to learn to do for ourselves by guiding our own evolution.</em></blockquote> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>In 2010, Knowledge Federation began to self-organize to become capable of making further headway on this creative frontier. The procedure we developed is simple: We create a [[prototype|<em>prototype</em>]] of a system, and organize a <em>transdisciplinary</em> community and project around it, to update it continuously. This enables the insights reached in the participating disciplines to have real or <em>systemic</em> impact <em>directly</em>.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Our very first project of this kind, the Barcelona Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism in 2011, developed a [[prototype|<em>prototype</em>]] of a public informing that turns perceived problems (that people report directly, through citizen journalism) into <em>systemic</em> understanding of causes and recommendations for action (developed by involving academic and other domain experts, and having their insights made accessible by a communication design team). </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The experience with this <em>prototype</em> revealed a general paradox we were not aware of: The senior domain experts we brought together to represent (in this case) journalism <em>cannot change their own system</em> (their full capacity being engaged in performing their role within the system). What they, however, can and need to do is empower their next-generation (students, junior colleagues, entrepreneurs...) to do that. A year later we created The Game-Changing Game as a generic way to change <em>systems</em>—and hence as a "practical way to craft the future". We subsequently created The Club of Zagreb, as an update (<em>necessary</em> to unravel this paradox) of The Club of Rome. The Holotopia project builds further on the results of this work.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Our portfolio contains about forty [[prototype|<em>prototypes</em>]], each of which illustrates [[systemic innovation|<em>systemic innovation</em>]] in a specific domain. Each <em>prototype</em> is composed by weaving together [[design pattern|<em>design patterns</em>]]—problem-solution pairs, which are ready to be adapted to other design challenges and domains.</p> |

| + | <p>The Collaborology <em>prototype</em>, in education, will highlight some of the advantages of this approach.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> An education that prepares us for yesterday's professions, and only in a certain stage of life, is obviously an obstacle to <em>systemic</em> change. Collaborology implements an education that is in every sense flexible (self-guided, life-long...), and in an <em>emerging</em> area of interest (collaborative knowledge work, as enabled by new technology). By being collaboratively created itself (Collaborology is created and taught by a network of international experts, and offered to learners world-wide), the economies of scale result that <em>dramatically</em> reduce effort. This in addition provides a sustainable business model for developing and disseminating up-to-date knowledge in <em>any</em> domain of interest. By conceiving the course as a design project, where everyone collaborates on co-creating the learning resources, the students get a chance to exercise their "human quality". This in addition gives the students an essential role in the resulting 'knowledge-work ecosystem' (as 'bacteria', extracting 'nutrients') .</p> | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| − | |||

| Line 262: | Line 270: | ||

<div class="col-md-7"><h3>Scope</h3> | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>Scope</h3> | ||

| + | <p>We have just seen that our evolutionary challenge and opportunity is to develop the capability to update our institutions or <em>systems</em>, to learn how to make them <em>whole</em>.</p> | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote><b>Where</b>—with what system—shall we begin?</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | |

| − | <p>Norbert Wiener | + | <p>The handling of information, or metaphorically our society's 'headlights', suggests itself as the answer for several reasons. </p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>One of them is obvious: If we should use information as guiding light and not competition, our information will need to be different.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>In his 1948 seminal "Cybernetics", Norbert Wiener pointed to another reason: In <em>social</em> systems, communication is what <em>turns</em> a collection of independent individuals into a system. Wiener made that point by talking about ants and bees. It is the nature of the communication that determines a social system's properties, and behavior. Cybernetics has shown—as its main point, and title theme—that "the tie between information and action" has an all-important role, which determines (Wiener used the technical keyword "homeostasis, but let us here use this more contemporary one) the <em>sustainability</em> of a system. The full title of Wiener's book was "Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine". To be able to correct their behavior and maintain inner and outer balance, to be able to "change course" when the circumstances demand that, to be able to continue living and adapting and evolving—a system must have <em>suitable</em> communication and control.</p> | ||

<h3>Diagnosis</h3> | <h3>Diagnosis</h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>That is presently <em>not</em> the case with our core systems; and with our civilization as a whole..</p> | ||

<blockquote>The tie between information and action has been severed, Wiener too observed. </blockquote> | <blockquote>The tie between information and action has been severed, Wiener too observed. </blockquote> | ||

| − | <p>Our society's communication-and-control is broken | + | <p>Our society's communication-and-control is broken; it needs to be restored.</p> |

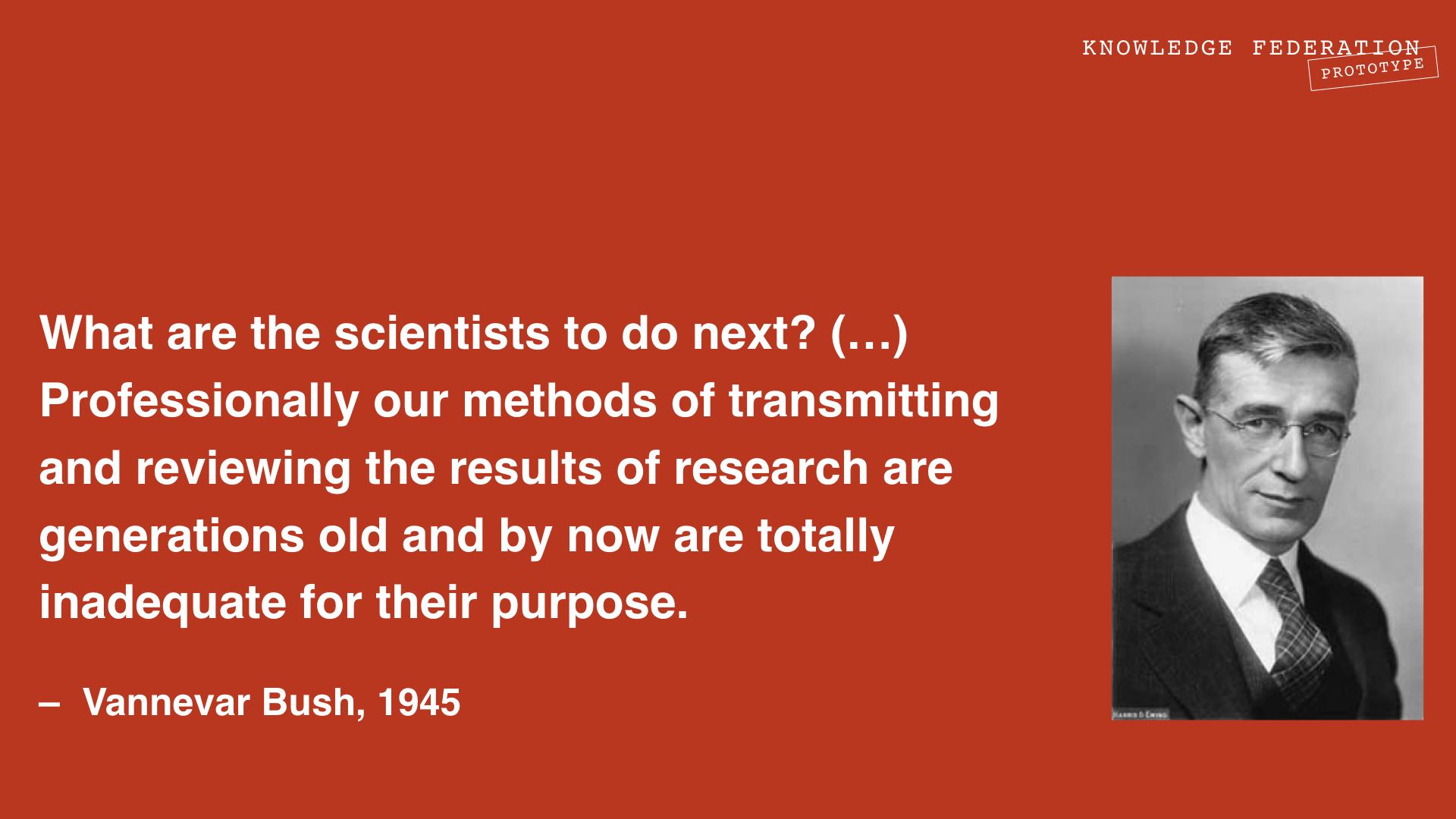

<p> | <p> | ||

[[File:Bush-Vision.jpg]] | [[File:Bush-Vision.jpg]] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <p>To make that point, Wiener cited an earlier work, Vannevar Bush's 1945 article "As We May Think", where Bush urged the scientists to make the task of revising <em>their | + | <p>To make that point, Wiener cited an earlier work, Vannevar Bush's 1945 article "As We May Think", where Bush urged the scientists to make the task of revising <em>their</em> communication their <em>next</em> highest priority—the World War Two having just been won.</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>These calls to action remained, however, without effect.</blockquote> |

| − | <p>"As long as a paradox is treated as a problem, it can never be dissolved," observed David Bohm.</p> | + | <p>"As long as a paradox is treated as a problem, it can never be dissolved," observed David Bohm. <em>Wiener too</em> entrusted his insight to the communication whose tie with action had been severed.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>We have assembled a formidable collection of academic results that shared the same fate—to illustrate a general phenomenon we are calling [[Wiener's paradox|<em>Wiener's paradox</em>]]. The link between communication and action having been broken—the academic results will tend to be ignored <em>whenever they challenge the present "course"</em> and point to a new one!</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>To an academic researcher, it may feel disheartening to see so many best ideas of our best minds ignored. Why publish more—if even the most <em>elementary</em> insight that our field has produced, the one that <em>motivated</em> our field and our work, has not yet been communicated to the public?</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>This sentiment is transformed into <em>holotopian</em> optimism when we look at 'the other side of the coin'—the creative frontier that is opening up. We are invited to, we are indeed <em>obliged</em> to reinvent <em>the systems in which we live and work</em>, by recreating the very communication that holds them together. Including, of course, our own, academic system, and the way in which it interoperates with other systems—<em>or fails</em> to interoperate. </p> |

| − | <p>Optimism | + | <p>Optimism will turn into enthusiasm, when we consider also <em>this</em> commonly ignored fact:</p> |

| − | <blockquote> | + | <blockquote>The information technology we now commonly use to communicate with the world was <em>created</em> to enable a paradigm change on that very frontier.</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>'Electricity', and the 'lightbulb', have just been created—in order to <em>enable</em> the development of the new kinds of 'socio-technical machinery' that our society now urgently needs.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Vannevar Bush pointed to the need for this new paradigm already in his title, "As We May Think". His point was that "thinking" really means making associations or "connecting the dots". And that—given the vast volumes of our information—our knowledge work must be organized <em>in a way that enables us to benefit from each other's thinking</em>. That technology and processes must be devised to enable us to in effect "connect the dots" or think <em>together</em>, as a single mind does. Bush described a <em>prototype</em> system called "memex", which was based on microfilm as technology.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>Douglas Engelbart, however, took Bush's idea in a whole new direction—by observing (in 1951!) that when each of us humans are connected to a personal digital device through an interactive interface, and when those devices are connected together into a network—then the overall result is that we are connected together as the cells in a human organism are connected by the nervous system. </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Notice that the earlier innovations in this area—including both the clay tablets and the printing press—required that a physical object be <em>transported</em>; this new technology allows us to "create, integrate and apply knowledge" <em>concurrently</em>, as cells in a human nervous system do.</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote> We can now develop insights and solutions <em>together</em>! We can have results <em>instantly</em>!</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Engelbart saw in this new technology exactly what we need to become able to handle the "complexity times urgency" of our problems, which grows at an accelerated rate. </p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>[https://youtu.be/cRdRSWDefgw This three minute video clip], which we called "Doug Engelbart's Last Wish", offers an opportunity for a pause. Imagine the effects of improving the planetary <em>systems</em>, and our "development, integration and application of knowledge" to begin with. Imagine "the effects of getting 5% better", Engelbart commented with a smile. Then our old man put his fingers on his forehead, and looked up: "I've always imagined that the potential was... large..." The potential is not only large, it is <em>staggering</em>. The improvement that is both necessary and possible is <em>qualitative</em>—from a system that doesn't work, to one that does.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>To Engelbart's dismay, this new "collective nervous system" ended up being use to only make the <em>old</em> processes and systems more efficient. The ones that evolved through the centuries of use of the printing press. The ones that <em>broadcast</em> information. </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

[[File:Giddens-OS.jpeg]] | [[File:Giddens-OS.jpeg]] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | < | + | |

| + | <blockquote>The above observation by Anthony Giddens points to the impact this has had on our culture; and on "human quality".</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

<p>Dazzled by an overload of data, in a reality whose complexity is well beyond our comprehension—we have no other recourse but "ontological security". We find meaning in learning a profession, and performing in it a competitively.</p> | <p>Dazzled by an overload of data, in a reality whose complexity is well beyond our comprehension—we have no other recourse but "ontological security". We find meaning in learning a profession, and performing in it a competitively.</p> | ||

| − | <p>But | + | <p>But that is exactly what <em>binds us</em> to <em>power structure</em>. </p> |

<h3>Remedy</h3> | <h3>Remedy</h3> | ||

| − | < | + | <p><em>What is to be done</em>, to restore the severed link between communication and action?</p> |

| + | <blockquote><em>How can we begin to change our collective mind</em>—as our technology enables, and our situation demands?</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Engelbart left us a clear and concise answer; he called it <em>bootstrapping</em>.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>His point was that only <em>writing</em> about what needs to be done would not have an effect (the tie between information and action having been broken). <em>Bootstrapping</em> means that we consider ourselves as a part in a larger whole; and that we self-organize, and behave, as it may best serve to restore its <em>wholeness</em>. Which practically means that we either <em>create</em> a new system by using our own minds and bodies, or help others do that.</p> |

| + | <p>The Knowledge Federation <em>transdiscipline</em> was created by an act of <em>bootstrapping</em>, to enable <em>bootstrapping</em>. What we are calling <em>knowledge federation</em> may now simply be understood as the functioning of a proper <em>collective mind</em>; including all the functions and processes this may require. Obviously, the impending <em>collective mind</em> re-evolution itself requires a <em>system</em>, or an institution, which will assemble and mobilize the required knowledge and human and other resources toward that end. Our first priority must be to secure that. Presently, Knowledge Federation is (a complete <em>prototype</em> of) the <em>transdiscipline</em> for <em>knowledge federation</em>—ready for inspection and deployment. We offer it as a proof-of-concept implementation of our call to action.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>The <em>praxis</em> of <em>knowledge federation</em> itself must be <em>federated</em>. In 2008, when Knowledge Federation had its inaugural meeting, two closely related initiatives were formed: Program for the Future (a Silicon Valley-based initiative to continue and complete "Doug Engelbart's unfinished revolution") and Global Sensemaking (an international community of researchers and developers, working on technology and processes for collective sense making). </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:BCN2011.jpg]]<br> |

| + | <small>Patty Coulter, Mei Lin Fung and David Price speaking at the 2011 An Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism workshop in Barcelona</small> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>We use the above triplet of photos ideographically, to highlight that Knowledge Federation is a true federation—where state of the art knowledge is combined in state of the art <em>systems</em>. The featured participants of our 2011 workshop in Barcelona, where our public informing <em>prototype</em> was created, are Patty Coulter (the Director of Oxford Global Media and Fellow of Green College Oxford, formerly the Director of Oxford University's Reuter Program in Journalism) Mei Lin Fung (the founder of Program for the Future) and David Price (who co-founded both the Global Sensemaking R & D community, and Debategraph—which is now the leading global platform for collective thinking). | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Other <em>prototypes</em> contributed other <em>design patterns</em> for restoring the severed link between information and action. The Tesla and the Nature of Creativity TNC2015 <em>prototype</em> showed what may constitute the <em>federation</em> of a research result—which is written in an esoteric academic vernacular, and has large potential general interest and impact. The first phase of this <em>prototype</em>, completed through collaboration between the author and our communication design team, turned the academic article into a multimedia object, with intuitive, metaphorical diagrams, and explanatory interviews with the author. The second phase was a high-profile, televised and live streamed event, where the result was made public. The third phase, implemented on Debategraph, modeled proper online collective thinking about the result—including pros and cons, connections with other related results, applications etc. </p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>The Lighthouse 2016 <em>prototype</em> is a conceived as a <em>direct</em> remedy for the <em>Wiener's paradox</em>, created for and with the International Society for the Systems Sciences. This <em>prototype</em> models a system by which an academic community can <em>federate</em> a single message into the public sphere. The message in this case was also relevant—it was whether or not we can rely on "free competition" to guide the evolution and the functioning of our <em>systems</em> (or whether we must use its alternative—namely the knowledge developed in the systems sciences). </p> | ||

| − | + | </div> </div> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| − | <p> | + | <div class="row"> |

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>[[Holotopia:Socialized reality|<em>Socialized reality</em>]]</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3><em>Scope</em></h3> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <blockquote>"Act like as if you loved your children above all else",</blockquote> | ||

| + | Greta Thunberg, representing her generation, told the political leaders at Davos. <em>Of course</em> political leaders love their children—don't we all? But what Greta was asking them to do was to 'hit the brakes'; and when the 'bus' they are believed to be 'driving' is inspected, it becomes clear that the 'brakes' too are missing. The job of a politician is to keep 'the bus on course' (the economy growing) for yet another four years. <em>Changing</em> the 'course' or the <em>system</em> is well beyond what they are able to do, or even imagine doing.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The COVID-19 pandemic may require systemic changes <em>now</em>.</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>So <b>who</b>, what institution or <em>system</em>, will lead us through our <em>next</em> evolutionary challenge—where we will learn how to recreate <em>the systems in which we live and work</em>; in <em>knowledge work</em>, and beyond?</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Both Erich Jantsch and Doug Engelbart believed that "the university" would have to be the answer; and they made their appeals accordingly. But the universities ignored them—just as they ignored Vannevar Bush and Norbert Wiener before them, and so many others who followed. </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Why?</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Isn't the call to restore agency to information and power to knowledge deserving of academic attention?</p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>It is tempting to conclude that the university institution followed the general trend, and evolved as a <em>power structure</em>. But to see solutions, we need to look at deeper causes.</p> |

| + | <p> | ||

| + | [[File:Toulmin-Vision2.jpeg]] | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| − | </ | + | <p>We readily find them in the way in which the university institution <em>originated</em>.</p> |

| + | <p>The academic tradition did not originate as a way to practical knowledge, but to <em>freely</em> pursue knowledge for its own sake; in a manner disciplined only by [[knowledge of knowledge|<em>knowledge of knowledge</em>]]—which philosophers have been developing since antiquity. Wherever this free-yet-disciplined pursuit of knowledge took us, we followed.</p> | ||

| − | + | <p>And as we pointed out in the opening paragraphs of this website, by highlighting the iconic image of Galilei in house arrest, | |

| + | <blockquote>it was this <em>free</em> pursuit of knowledge that led to the <em>last</em> "great cultural revival".</blockquote> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>We asked: |

| − | + | <blockquote>Could a similar advent be in store for us today?</blockquote></p> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <blockquote> | ||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The key to the positive answer to this question—which is obviously central to <em>holotopia</em>—is in the <em>historicity</em> of "the relationship we have with knowledge"—which Stephen Toulmin explicated so clearly in his last book, "Reurn to Reason", from which the above quotation was taken. So that is what we here focus on.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>As Toulmin pointed out, at the time when the modern university was taking shape, it was the Church and the tradition that had the prerogative of telling the people how to conduct their daily affairs and what to believe in. And as the image of Galilei in house arrest might suggest—they held onto that prerogative most firmly! But the censorship and the prison could not stop an idea whose time had come. They were unable to prevent a completely <em>new</em> way to explore the world to transpire from astrophysics, where it originated, and transform first our pursuit of knowledge—and then our society and culture at large.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>It is therefore natural that at the universities we consider the curation of this <em>approach</em> to knowledge to be our core role in our society. At the universities, we are the heirs and the custodians of a tradition that has historically led to some of <em>the</em> most spectacular evolutionary leaps in human history. Naturally, we remain faithful to that tradition. We do that by meticulously conforming to the methods and the themes of interests of mathematics, physics, philosophy, biology, sociology, philosophy and other traditional academic disciplines, which, we believe, <em>embody</em> the highest standards of <em>knowledge of knowledge</em>. People can learn practical skills elsewhere. It is the <em>university</em> education that gives them them up-to-date <em>knowledge of knowledge</em>—and with it the ability to pursue knowledge correctly in <em>any</em> field of interest.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>We must ask:</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>Can the academic tradition evolve further? </blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Could this tradition <em>once again</em> give us a completely <em>new</em> way to explore the world?</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Can the free pursuit of knowledge, curated by the <em>knowledge of knowledge</em>, once again lead to "a great cultural revival" ?</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>Can "a great cultural revival" <em>begin</em> at the university?</blockquote> |

| − | |||

<h3>Diagnosis</h3> | <h3>Diagnosis</h3> | ||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <blockquote>In the course of our modernization, we made a <em>fundamental error</em>.</blockquote> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>From the traditional culture we have adopted a <em>myth</em> far more disruptive of modernization than the creation myth—that "truth" means "correspondence with reality"; and that the purpose of information, and of our pursuit of knowledge, is to "know the reality" objectively, as it truly is. It may take a moment of reflection to see how much this <em>myth</em> permeates our popular culture, our society and institutions; how much it marks "the relationship we have with information"—in all its various manifestations.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>This fundamental error has subsequently been detected and reported, but not corrected. (We again witness that the link between information and action has been severed.)</p> | ||

| − | |||

<p> | <p> | ||

[[File:Einstein-Watch.jpeg]] | [[File:Einstein-Watch.jpeg]] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p><em>It is simply impossible</em> to open up the 'mechanism of nature', and verify that our ideas and models <em>correspond</em> to the real thing!</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The "reality", the 20th century's scientists and philosophers found out, is not something we discover; it is something we <em>construct</em>. </blockquote> |

| − | <p>" | + | <p>Our "construction of reality" turned out to be a complex and most interesting process, in which our cognitive organs and our society or culture interact. From the cradle to the grave, through innumerably many "carrots and sticks", we are <em>socialized</em> to organize and communicate our experience <em>in a certain specific way</em>. </p> |

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The vast body of research, and insights, that resulted in this pivotal domain of interest, now allows us and indeed <em>compels us</em> to extend the <em>power structure</em> view of social reality a step further, into the cultural and the cognitive realms.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>In "Social Construction of Reality", Berger and Luckmann left us an analysis of the social process by which the reality is constructed—and pointed to the role that "universal theories" (which determine the relationship we have with information) play in maintaining a given social and political status quo. An example, but not the only one, is the Biblical worldview of Galilei's persecutors.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>To organize and sum up what we above all need to know about the <em>nature</em> of <em>socialization</em>, and its relationship with power, we created the Odin–Bourdieu–Damasio [[thread|<em>thread</em>]], consisting of three short real-life stories or [[vignette|<em>vignettes</em>]]. (The <em>threads</em> are a technical tool we developed based on Vannevar Bush's idea of "trails"; we call them "threads" because we further weave them into <em>patterns</em>.) These insights are so central to <em>holotopia</em>, that we don't hesitate to summarize them also here, however briefly.</p> |

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The first, Odin the Horse story, points to the nature of turf struggle, by portraying the turf behavior of horses. </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The second story, featuring Pierre Bourdieu as leading sociologist, shows that we humans exhibit a similar behavior—albeit in far more varied, complex and subtle ways. In effect, Bourdieu's experiences and insights in Algeria, which led to the formulation of his "theory of practice", allow us to perceive the human culture as—a complex 'turf'.</p> |

| + | <p> | ||

| + | [[File:Bourdieu-insight.jpeg]] | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>Bourdieu used interchangeably two keywords—"field" and "game"—to refer to this 'turf'. By calling it a field, he suggested something akin to a magnetic field, which orients our seemingly random or "free" behavior—mostly without anyone noticing that. By calling it a game, he sugged something that structures or "gamifies" our social existence, by giving each of us certain "action capabilities" pertaining to a social role. Those "embodied predispositions" or capabilities, which Bourdieu called "habitus", tend to be transmitted from body to body <em>directly</em>—without anyone noticing that a subtle "turf strife" is at play. Everyone bows to the king, and spontaneously we do too. In this way we are <em>socialized</em>—through innumerably many carrots and sticks—to accept those roles, and the behaviors or capabilities associated with them, as simply <em>the</em> "reality"—and hence as similarly immutable or "objectively" given as the reality of the material world. Bourdieu called this experience, that (our perception of) the social <em>and</em> natural "reality" is the only one possible, <em>doxa</em>. </p> | ||

| − | <p>The | + | <p>The third story, featuring Antonio Damasio in the role of a leading cognitive neuroscientist, completes this <em>thread</em> by explaining that we, humans, are <em>not</em> the rational decision makers, as the founding fathers of the Enlightenment made us believe. Each of us has an <em>embodied</em> cognitive filter, which <em>determines what options</em> we are able to rationally consider. This cognitive filter is <em>programmed</em> through <em>socialization</em>. Damasio's insight allows us to understand why we civilized humans don't even rationally <em>consider</em> taking off our clothes and walking into the street naked; <em>and most importantly</em>—why we don't consider changing <em>the systems in which we live and work</em>.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The most important insight reached is the following.</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote><em>Socialized reality</em> construction constitutes a <em>pseudo-epistemology</em>.</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Socialization can make certain things and ideas seem real—and others unreal.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>We have deliberately chosen Socrates (the forefather of Academia) and Galilei (a pioneer of science) to represent the academic tradition in our proposal. Both Socrates and Galilei were charged and sentenced for "impiety" (challenging <em>socialized reality</em>), and for <em>epistemology</em> (which Socrates practiced through <em>dialogs</em>, and Galilei by allowing the reason to challenge the truth of the Scripture). Thereby we pointed out that substituting <em>knowledge of knowledge</em> for <em>socialized reality</em> construction has been <em>the</em> core theme of the academic tradition since its inception. </p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | </p> | + | <blockquote>But <em>socialized reality</em> construction is not only or even primarily an instrument of power struggle. It is, indeed, also <em>the</em> way in which the traditional culture reproduces itself and evolves. It is the very 'DNA' of the traditional culture, and often the only one that was available.</blockquote> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>We may perceive the traditional "realities"—such as the belief in heavenly reward and the eternal punishment—as instruments of power; <em>and</em> we may also see them as ways in which certain cultural values, and certain "human quality", were maintained. Both perceptions correct; and both are relevant. </p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>It is their historical <em>interplay</em> that is most interesting to study—how the best insights of the best among us, of the historical enlightened beings and "prophets", were diverted to serve the <em>power structure</em>, and turned something quite <em>opposite</em> from what was intended. In the Holotopia project we engage in this sort of study to develop answers to perhaps <em>the</em> most interesting question, in any case from the point of view of the <em>holotopia</em>:</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>What would our world be like, if we <em>liberated</em> the culture from the <em>power structure</em>?</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Some of the consequences of the historical error under consideration (that we adopted <em>reification</em> as "the relationship we have with information") include the following.</p> |

| − | < | + | <ul> |

| + | <li><b>Undue limits to creativity</b>. On the one side we have a vast global army of selected, specially trained and publicly sponsored creative workers having to produce <em>more</em> articles in the traditional academic fields as the <em>only</em> way to be academically legitimate. On the other side of our society, and of our planetary ecosystem, in dire need for <em>new</em> ideas, for <em>new</em> ways to be creative. Imagine the amount of benefit that could be reached in that situation— by <em>liberating</em> the contemporary Galilei to once again bring completely <em>new</em> ways to create and handle knowledge!</li> | ||

| − | < | + | <li><b>Severed link between information and action</b>. The (perceived) purpose of information being to complete the 'reality puzzle'—every new piece appears to be equally relevant as the others, and necessary for completing this project. In the sciences, and in media informing, we keep producing large volumes of data every minute—as Neil Postman diagnosed. As the ocean of documents rises, we begin to drown in it. Informing us the people in some functional way becomes impossible.</li> |

| + | <li><b>Loss of cultural heritage</b>. We may as well here focus on the cultural heritage whose purpose was to cultivate "human quality". Already this trivial observation might suffice to make a point: With the threat of eternal fire on the one side, and the promise of heavenly pleasures on the other, a 'field' is created that orients the people's behavior toward what the tradition considered ethical. To see that those ancient myths are, however, only the tip of an iceberg (or more to the point, only elements in a complex ecosystem whose purpose is <em>socialization</em>) a one-minute thought experiment—an imaginary visit to a cathedral—will be sufficient. There is awe-inspiring architecture; frescos of masters of old on the walls; we hear Bach cantatas; and there's of course the ritual. All this comprises an ecosystem—where emotions such as respect and awe make one to listening and learning in certain ways, and advancing further. The complex dynamics of our <em>cultural</em> ecosystem, and the way we handled it, bear a strong analogy with our biophysical environment, with one notable difference: We have neither concepts nor methods, we have nothing equivalent to the temperature and the CO2 measurements in culture—to even diagnose the problems; not to speak about legislating remedies. </li> | ||

| − | < | + | <li><b>"Human quality" abandoned to <em>power structure</em></b>. Advertising is everywhere. And <em>explicit</em> advertising too is only a tip of an iceberg, the bulk of shich consists of a variety of ways in which "symbolic power" is used to <em>socialize</em> us in ways that suit the <em>power structure</em> interests. As a rule, this proceeds without anyone's awareness, as Bourdieu observed. But the organized and <em>deliberate</em>, and even research-based manipulation should not be underestimated! Here the [https://youtu.be/lOUcXK_7d_c person and the story of Edward Bernays], Freud's American nephew who became "the pioneer of modern public relations and propaganda", is iconic.</li> |

| + | </ul> | ||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>This conclusion suggests itself.</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The Enlightenment did not liberate us from power-related reality construction, as it is believed.</blockquote> |

| + | <blockquote>Our <em>socialization</em> only changed hands—from the kings and the clergy, to the corporations and the media.</blockquote> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>Ironically, our carefully cultivated self-identity—as "objective observers of reality"—keeps us, academic researchers, and information and knowledge at large, on the 'back seat'—and without impact. We can, and do, diagnose problems; but we cannot be an active agent in their solution.</p> |

<h3>Remedy</h3> | <h3>Remedy</h3> | ||

| + | <p>In the spirit of the <em>holoscope</em>, we introduce an answer by a metaphorical image, the Mirror <em>ideogram</em>. As the <em>ideograms</em> tend to, the Mirror <em>ideogram</em> too renders the essence of a situation, in a way that points to a way in which the situation may need to be handled—<em>and</em> to some subtler points as well.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>The main message of the Mirror [[ideogram|<em>ideogram</em>]] is that the free-yet-methodical pursuit of knowledge, which distinguishes the academic tradition, has brought us to a certain singular situation, which requires that we respond in a certain specific way. The <em>mirror</em> is inviting us, and indeed <em>compelling</em> us to interrupt the busy work we are doing, and to self-reflect in a similar manner and about similar themes as Socrates taught, at the point of the Academia's inception many centuries ago.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>When we look at a mirror, we see ourselves—and we see ourselves <em>in the world</em>. The [[mirror|<em>mirror</em>]] metaphor is intended to reflect two insights, or two changes in our habitual self-identity and self-perception, which a self-reflection about the underlying issues of meaning and purpose, based on the academic insights reached in the past century, will lead us to. </p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The first insight is that we must put an end to <em>reification</em>. Seeing ourselves in the <em>mirror</em> is intended to signify that the methods and vocabularies of the academic disciplines were not something that objectively existed, and was only discovered. <em>We</em> (the founders of our disciplines) <em>created</em> them. For <em>many</em> reasons, some of which have been stated above, we must liberate ourselves, and the people, from <em>reification</em> of our institutions, our worldviews, and of the very concepts we use to communicate. </p> |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>The liberation from <em>reification</em> is the liberation from the <em>systems</em> we have been socialized to accept as "reality"—and hence also from the <em>power structure</em>.</blockquote> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | [[File:Mirror2.jpg]]<br> | ||

| + | <small>Mirror <em>ideogram</em></small> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

| + | <p>The second consequence is the beginning of <em>accountability</em>. The world we see ourselves in is a world that needs <em>new</em> ideas, new ways of thinking, and of <em>being</em>. It's a world in dire need for creative yet methodical and <em>accountable</em> change. We see the key role that information and knowledge have in that world, and that situation. </p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <blockquote>We see ourselves <em>holding</em> the key.</blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>An important point here is that the <em>academia</em> finds itself in a much larger and more important role than the one it was originally conceived for. The reason is a historical accident: The successes of science discredited the <em>foundations</em>, beginning from its <em>socialized reality</em>, on which the traditional culture relied in its function.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The key question then presents itself:</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>How should we continue?</blockquote> |

| − | < | + | <p>Yes, we do want to respond to our new role; indeed <em>we have to</em>, because nobody else can.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>At the same time—we do want to continue our tradition, of free–yet-methodical pursuit of knowledge for its own sake.</p> |

| + | <p>The most interesting insight reflected by the <em>mirror</em> is that we <em>can</em> do both. There is a way to <em>both</em> take care of the fundamental problem (liberate ourselves and the people from <em>reification</em>) <em>and</em> respond to this larger role.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Philosophically, <em>and</em> practically, this seemingly impossible or 'magical' way out of our double-bind, is to walk through the <em>mirror</em>. This can be done in only two steps.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>The first is to use what philosopher Villard Van Orman Quine called "truth by convention"—which we adapted as one of our <em>keywords</em>.</p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

[[File:Quine–TbC.jpeg]] | [[File:Quine–TbC.jpeg]] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Quine opened "Truth by Convention" by observing:</p> |

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | "The less a science has advanced, the more its terminology tends to rest on an uncritical assumption of mutual understanding. With increase of rigor this basis is replaced piecemeal by the introduction of definitions. The interrelationships recruited for these definitions gain the status of analytic principles; what was once regarded as a theory about the world becomes reconstrued as a convention of language. Thus it is that some flow from the theoretical to the conventional is an adjunct of progress in the logical foundations of any science." | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>But if <em>truth by convention</em> has been the way in which <em>the sciences</em> augment the rigor of their logical foundations—why not use it to update the logical foundations of <em>knowledge work</em> at large?</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>As we are using this [[keyword|<em>keyword</em>]], the [[truth by convention|<em>truth by convention</em>]] is the kind of truth that is common in mathematics: "Let <em>X</em> be <em>Y</em>. Then..." and the argument follows. Insisting that <em>x</em> "really is" <em>y</em> is obviously meaningless. A convention is valid only <em>within a given context</em>—which may be an article, or a theory, or a methodology.</p> |

| − | <p>The | + | <p>The second step is to use <em>truth by convention</em> to define an <em>epistemology</em>.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>We defined [[design epistemology|<em>design epistemology</em>]] by turning the core of our proposal (to change the relationship we have with information—by considering it a human-made thing, and adapting information and the way we handle it to the functions that need to be served) into a convention.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>Notice that nothing has been changed in the traditional-academic scheme of things. The <em>academia</em> has only been <em>extended</em>; a new way of thinking and working has been added to it, for those who might want to engage in that new way. On the 'other side of the <em>mirror</em>', we see ourselves and what we do as (part of) the 'headlights' and the 'light'; and we self-organize, and act, and use our creativity freely-yet-responsibly, and create a variety of new methods and results—just as the founding father of science did, at the point of its inception. </p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | < | + | <p>In the "Design Epistemology" research article (published in the special issue of the Information Journal titled "Information: Its Different Modes and Its Relation to Meaning", edited by Robert K. Logan) where we articulated this proposal, we made it clear that the <em>design epistemology</em> is only one of the many ways to manifest this approach. We drafted a parallel between the <em>modernization</em> of science that can result in this way and the emergence of modern art: By defining an <em>epistemology</em> and a <em>methodology</em> by convention, we can do in the sciences as the artists did—when they liberated themselves from the demand to mirror reality, by using the techniques of Old Masters. </p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote>As the artists did—we can become creative <em>in the very way in which we practice our profession.</em></blockquote> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>To complete this proposal—to the <em>academia</em> to 'step through the <em>mirror</em>' and to guide our society to a new reality—we developed the two <em>prototypes</em>—of the <em>holoscope</em> (to model the academic reality on the other side) and of the <em>holotopia</em> (to model the social reality).</p> |

| − | <p><em> | + | <p>Technically or academically, each of them is a model of a <em>paradigm</em>—hence we have a <em>paradigm</em> in <em>knowledge work</em> ready to foster for a larger societal <em>paradigm</em>—exactly as the case was in Galilei's time.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>We bring these lofty and "up in the air" possibilities down to earth, by discussing one of the more immediately practical consequences of the proposed course of action.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The [[keyword|<em>keywords</em>]] we've been using all along are all defined by convention.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The discussions of two examples—of [[design|<em>design</em>]] and [[implicit information|<em>implicit information</em>]]—which we offer separately, and here only summarize—will illustrate subtle yet central advantages this approach offers. Each of those [[keyword|<em>keywords</em>]] has been proposed to corresponding academic communities, and well received. Hence they are also [[prototype|<em>prototypes</em>]]—illustrating the possibility and the need for assigning purpose, by convention, to already <em>existing</em> academic fields and practices.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>The definition of <em>design</em> allowed us to capture the essence of our post-traditional cultural condition—and suggest how we need to adapt to it—in a single word.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>We defined <em>design</em> as "alternative to <em>tradition</em>", where <em>design</em> and <em>tradition</em> are two alternative ways to <em>wholeness</em>. <em>Tradition</em> relies on spontaneous, gradual, Darwinian-style evolution. Change is resisted. Small changes are tried—and tested and assimilated in the culture as a whole through generations of use. We practice <em>design</em> when we consider ourselves accountable for the <em>wholeness</em> of the result. The point here is that when <em>tradition</em> cannot be relied on—<em>design</em> must be used.</p> |

| − | <p>We | + | <p>The situation we are in—as depicted by the bus with candle headlights—can be understood as a result of a transition: We are no longer <em>traditional</em> (our technology evolves by <em>design</em>); but we are not yet <em>designing</em> ("the relationship we have with information" is still <em>traditional</em>). Our proposal can now be understood as the call to <em>complete</em> modernization. </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p><em>Reification</em> can now be understood as the foundation for truth and meaning that suits the <em>tradition</em>; <em>truth by convention</em> is what empowers us to <em>design</em>.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | </ | + | <p>We proposed this definition, and the insights and the methodology it is pointing to, to the design community as a way to develop its logical foundations. In the PhD Design's online conference the question, "What does it mean to give a doctorate in design?" Or in other words, "What should the academic criteria and the methods in design be based on?" The natural answer, the community leaders thought, would be classical philosophy; it is, after all, a <em>philosophy</em> doctorate that is being awardd. We proposed that classical philosophy as foundation also has its problems. But that we can <em>design</em> a foundation—by using <em>truth by convention</em>, and the approach we've drafted. </p> |

| − | < | + | <p>We offer the fact that Danish Designers chose our presentation to be repeated as opening keynote at their tenth anniversary conference, out of about three hundred that were shared at the triennial conference of the European Academy of Design, as a sign that this praxis, of assigning a purpose to a discipline and a community, and building a methodology on that basis, can be <em>practically</em> acceptable and useful. </p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

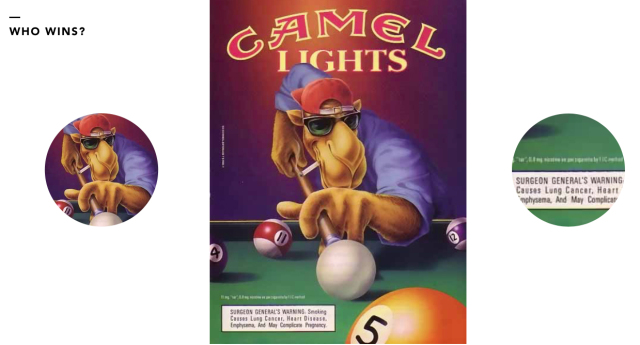

| − | <p> | + | <p>The definition of <em>implicit information</em> and of <em>visual literacy</em> as "literacy associated with <em>implicit information</em> for the International Visual Literacy Association was in spirit similar—and the point was similarly central.</p> |

| + | <p> | ||

| + | [[File:Whowins.jpg]] | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>We showed the above <em>ideogram</em> as depicting a situation where two kinds of information—the <em>explicit information</em> with explicit, factual and verbal warning in a black-and-white rectangle, and the visual and "cool" rest—meet each other in a direct duel. Our immeiate point was that the <em>implicit information</em> wins "hands down" (or else this would not be a cigarette advertising). Our larger point was that while our legislation, ethical sensibilities and "official" culture at large are focused on <em>explicit information</em>, our culture is largely created through subtle <em>implicit information</em>. Hence we need a <em>literacy</em> to be able to decode those messages. It is easy to see how this line of thought and action directly continues what's been told above about the negative consequences of <em>reification</em>. </p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | </div> </div> | |

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <div class="row"> |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>[[Holotopia:Narrow frame|<em>Narrow frame</em>]]</h2></div> | |

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3><em>Scope</em></h3> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>We have just seen, by highlighting the <em>historicity</em> of the academic approach to knowledge to reach the <em>socialized reality</em> insight, that the academic tradition—now instituted as the modern university—finds itself in a much larger and more central social role than it was originally conceived for. We look up to the <em>academia</em> (and not to the Church and the tradition) to tell us <b>how</b> to look at the world, to be able to comprehend it and handle it. </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>That role, and question, carry an immense power!</p> |

| + | <p>It was by providing a completely <em>new</em> answer to that question, that the last "great cultural revival" came about.</p> | ||

| − | < | + | <p>Could a similar advent be in store for us today?</p> |

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <h3>Diagnosis</h3> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>How <em>should</em> we look at the world, to be able to comprehend it and handle it? </blockquote> |

| + | <blockquote>Nobody knows! </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | <p>Of course, countess books and articles have been written about this theme since antiquity. But in spite of that—or should we rather say <em>because</em> of that—no consensus has been reached.</p> | |

| − | |||

| − | <p>Of course, | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Meanwhile, the way we the people look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it, shaped itself spontaneously—from the scraps of the scientific ideas that were available around the middle of the 19th century, when Darwin and Newton as cultural heroes replaced Adam and Moses. What is today popularly considered as the "scientific" worldview shaped itself then—and remained largely unchanged.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>As members of the <em>homo sapiens</em> species, this worldview makes us believe, we have the evolutionary privilege to be able to comprehend the world in causal terms, and to make rational choices based on such comprehension. Give us a correct model of the natural world, and we'll know exactly how to go about satisfying our needs (which we of course know, because we can experience them directly). But the traditional cultures, being unable to understand how the nature works, put a "ghost in the machine"—and made us pray to him to give us what we needed. Science corrected this error—and now we can satisfy our needs by manipulating the nature directly and correctly, with the help of technology. </p> |

| − | < | + | <p>It is this causal or "scientific" understanding of the world that makes us modern. Isn't that how we understood that women cannot fly on broomsticks?</p> |

| − | <p>From our collection of reasons | + | <p>From our collection of reasons why this way of looking at the world is neither scientific nor functional, we here mention two.</p> |

<p> | <p> | ||

[[File:Heisenberg–frame.jpeg]] | [[File:Heisenberg–frame.jpeg]] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <blockquote>The first | + | <blockquote>The first is that the nature is not a "machine".</blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The mechanistic or "classical" way of looking at the world that Newton and his contemporaries developed in physics, which around the 19th century shaped the worldview of the masses, has been disproved and disowned by modern science. Even <em>physical</em> phenomena, it has turned out, exhibit the <em>kinds of</em> interdependence that cannot be understood in causal terms.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>In "Physics and Philosophy", Werner Heisenberg, one of the progenitors of this research, described how "the narrow and rigid frame" as the way of looking at the world that our ancestors concocted from the 19th century science was damaging to culture, and in particular to religion and ethical norms on which the "human quality" depended. And how the prominence of "instrumental" thinking and values resulted, which Bauman called "adiaphorisation". Heisenberg explained how the modern physics <em>disproved</em> that worldview. Heisenberg expected that <em>the</em> largest impact of modern physics would be on culture—by allowing it to evolve further, by dissolving the <em>narrow frame</em>.</p> |

| − | <p>We | + | <p>In 2005, Hans-Peter Dürr (considered in Germany as Heisenberg's intellectual and scientific "heir") co-wrote the Potsdam Manifesto, whose title and message is "We need to learn to think in a new way". The proposed new thinking is conspicuously similar to the one that leads to <em>holotopia</em>: "The materialistic-mechanistic worldview of classical physics, with its rigid ideas and reductive way of thinking, became the supposedly scientifically legitimated ideology for vast areas of scientific and political-strategic thinking. (...) We need to reach a fundamentally new way of thinking and a more comprehensive understanding of our <em>Wirklichkeit</em> (world, or reality), in which we, too, see ourselves as a thread in the fabric of life, without sacrificing anything of our special human qualities. This makes it possible to recognize humanity in fundamental commonality with the rest of nature (...)"</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>The second reason is that even complex "machines" ("classical" nonlinear dynamic systems) cannot be understood in causal terms.</blockquote> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

[[File:MC-Bateson-vision.jpeg]] | [[File:MC-Bateson-vision.jpeg]] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||