Holotopia

Contents

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

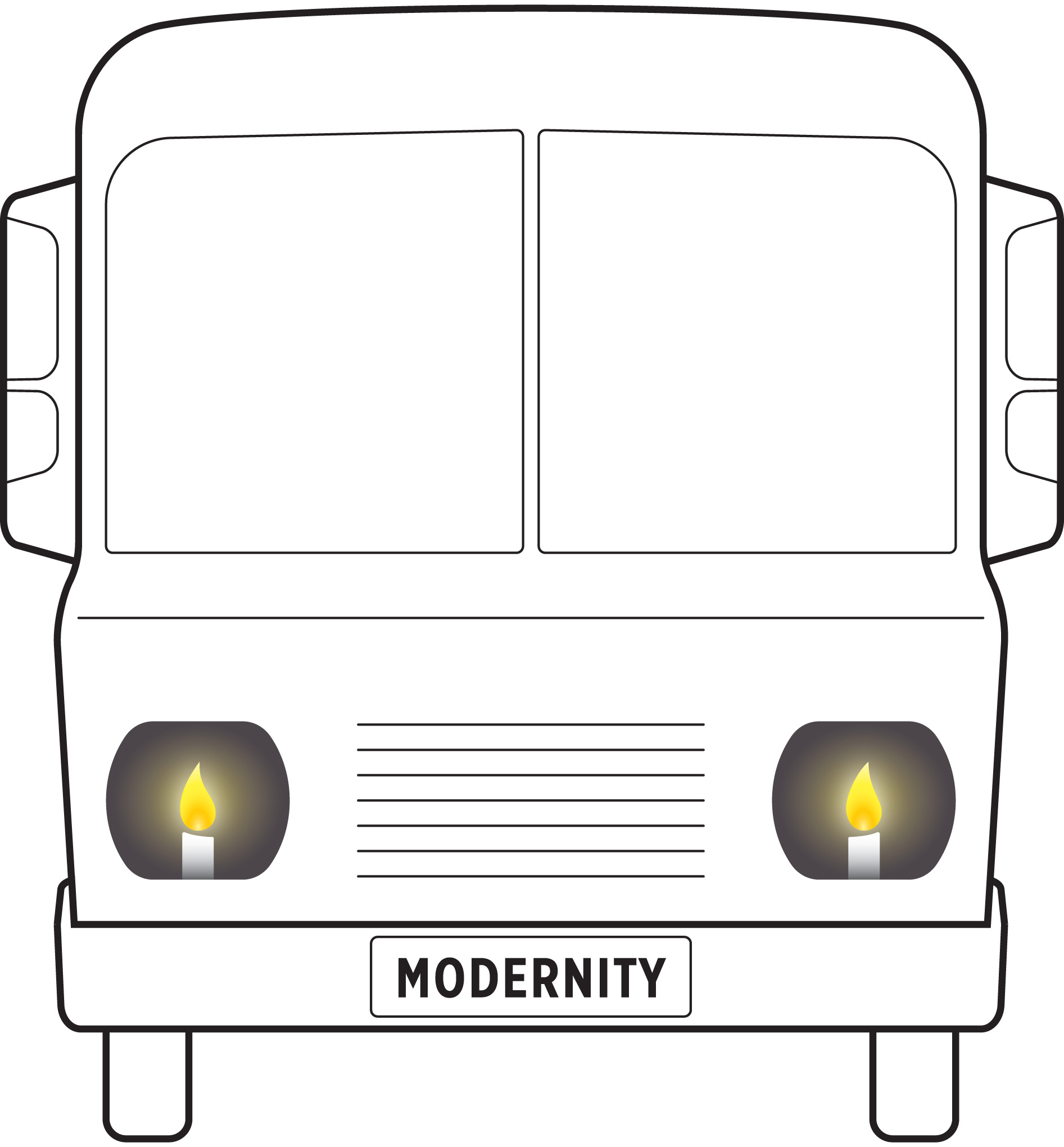

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Scope

"Act like as if you loved your children above all else",Greta Thunberg, representing her generation, told the political leaders at Davos. Of course the political leaders love their children—don't we all? But what Greta was asking for was to 'hit the brakes'; and when our 'bus' is inspected, it becomes clear that its 'brakes' too are dysfunctional. Changing the system, on the other hand, is well beyond what the politicians have the power to do, or even conceive of.

The COVID-19 crisis too is demanding systemic change.

So who, what institution or system, will lead us in "changing course" by changing the systems in which we live and work—our collective mind to begin with?

Both Jantsch and Engelbart believed that "the university" would have to be the answer; and they made their appeals accordingly. But the universities ignored them—as they ignored Bush and Wiener before them, and others who followed.

Why?

It is tempting to conclude that the university institution too followed the general trend, and organized itself as a power structure. But to see solutions, we need to look at deeper causes.

We readily find them in the way in which the university institution developed. The academic tradition did not originate as a way to pursue practical knowledge, but to freely pursue knowledge for its own sake.

And as we pointed out in the opening paragraphs of this website, by highlighting the iconic image of Galilei in house arrest,

it was this free pursuit of knowledge that led to the last "great cultural revival".

The ethos of the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake is deeply woven into the academic system and tradition—and for good reasons, as we have just seen. At the universities, we consider ourselves as the heirs and the custodians of a tradition that has historically led to some of the most spectacular evolutionary leaps in human history. Naturally, we remain faithful to this tradition; and we do that by meticulously following the interests and the processes of mathematics, physics, philosophy, biology, sociology and other traditional disciplines.

Can the academic tradition once again ignite a cultural revival?

This would, of course, be a natural and easy solution—considering the amount of talent, knowledge and social esteem the 'academic standing army' now owns, and its sheer size.

The key to the answer, the pivotal point of change or "the systemic leverage point" is, as we shall see, the academic self-perception—and that's what we will focus on.

Diagnosis

Two substantial changes developed during the last century, in the very determinants that shaped the academic tradition. One of them was pragmatic, the other one fundamental.

The pragmatic change is in the role that the academic tradition has in our society.

As Stephen Toulmin pointed out in "Return to Reason", from which the above excerpt was quoted, the academic system took shape in a culture where the Bible and the tradition had the prerogative to tell the people what to believe, what values to serve and how to behave. As the image of Galilei in house arrest might suggest, they held onto this prerogative most firmly!

It was by a historical accident that the academic tradition assumed a much larger roles in our society than it was prepared to perform.

The academic tradition acquired its new role, of curating the very relationship we have with information and with knowledge, and the power that accompanies it, by first discrediting and then replacing the Church and the tradition.

The fundamental change was in the way in which we conceive of information and knowledge, and of the very meaning of "truth" and "reality".

In the academic tradition and our society at large, it was generally considered as self-evident that "truth" means "correspondence with reality". And that the purpose of information is to give us real or true knowledge—of reality as it truly is.

It may take a moment of reflection to see how much this assumption now marks "the relationship we have with information"—in all its various manifestations.

This assumption, however, can no longer be rationally or academically maintained.

It is simply impossible to open up the 'mechanism of nature', and verify that our ideas and models correspond to the real thing!

How, then, did our "reality picture" come about?

Reality, the 20th century's scientists and philosophers found out, is not something we discover; it is something we construct.

And this "reality construction", this perception that our society's worldview and institutions are "reality" (which the sociologists called "doxa"), serves as an invisible yet all-powerful 'glue' that holds us together in a certain order of things; or as we called it, in a power structure

The Enlightenment did not liberate us from a rigid reality picture, and the power structure this may support, as it is believed.

Our socialization only changed hands—from the kings and the clergy, to modern corporations and the media.

Ironically, the traditional academic self-identity—as an "objective" observer of "reality"—is keeping the academia, and information and knowledge at large, in the "observer" role; without real impact.